by Caleb Centanni and Matthew Young:

How do you find a crossbill in western North America? Well, you have to know what’s on the menu. And, like a restaurant, if you want to know what’s on the menu, you need to know what’s in season. For crossbills, those seasons follows the cycles of conifer cone crops.

An Introduction to Crossbills

Evolution designed the crossbill’s crossed beak for one thing: eating the seeds out of conifer cones. Their beaks act like crowbars, allowing them to push the scales of cones aside and take the seed out. This seed is usually wrapped in a paper-like coating, which the birds remove with their beak and tongue.

Finding crossbills, first and foremost, means finding stands of cone-laden conifers. But you can tweak your odds by knowing the specific conifers found in your local mountains, when their cones will be on the menu for crossbills, and the details of the crossbill’s cone cycle year around which they schedule their lives. That cycle year starts roughly around the 1st of July, when cone crops for the year have mostly developed and have started to ripen, though this date can vary by species and elevation.

If you’re in search of Crossbills in western North America, you can count yourself lucky, since vast, elevationally stratified stands of pines, spruces, hemlocks, Douglas-firs, and other conifers keep them abundant and well-fed across the region. This contrasts with the eastern United States, where conifers are more diverse but also scarcer, supporting small resident Crossbill populations and occasional large irruptions.

We’ve put together this guide both so that new crossbill fans in the western US can start to find these birds on their own and lifelong Loxia-philes can polish their craft. We’ve included an intro to the many kinds of crossbills present in this vast region, plus the kinds of trees they are known to eat with a few comments on what they prefer from season to season.

Know Your Western Crossbills

There are two important classifications for crossbills: species and call type. The three species of Crossbills found in the west are Red Crossbill and White-winged Crossbill, which are distinguishable by plumage, calls, and song, and Cassia Crossbill, which can only be separated from Red Crossbill by calls. While all White-winged Crossbills generally sound similar, Red Crossbills show remarkable variation in the social calls they use during and just before they fly. There are currently 11 known variants of Red Crossbill flight calls (known as call types) in North America, 10 of which are documented in the West. Cassia Crossbill represents an additional type in the Red Crossbill vocal complex which was recently split into a distinct species based on research showing that it almost never mates with other types. In addition to their unique flight calls, each call type is known to have different average bill measurements and different favorite foods. It’s even been proposed that every call type has menu item that it relies on above all others, called a key conifer, but crossbill scientists don’t agree on whether this is always true.

So, without further ado, here are the must-know Crossbills of the western forest:

White-winged Crossbill: The small-billed crossbill of the high northern forests, White-winged crossbills prefer the sorts of soft-coned conifers you’d expect to find around a serene boreal bog or alpine meadow: spruces and tamarack. Fittingly, their cuisine of choice in the western mountains is Engelmann spruce, the only member of its genus available in most locations and the only common nesting tree for the species in the west. They also readily use both blue and Sitka spruces when their irruptions contact these trees. When spruce seed becomes scarce later in the cone cycle, they are known to switch to other soft-coned conifers like Douglas-fir, in which they nested abundantly in British Columbia in March 2019. The white-winged crossbill has a very small bill and lacks the strong jaw musculature of the Red Crossbill, limiting the trees it can efficiently feed on to meet the energetic requirements for breeding.

Type 2 “Ponderosa Pine” Red Crossbill: The most widespread large-billed crossbill in North America, Type 2 has such diverse foraging preferences that it may as well be called the “eclectic”, “eat everything”, or “not too picky” crossbill. That said, it does have a stronger affinity for ponderosa pines than any other type, often spending all seasons in the vast, copper-trunked stands of this tree that mark the boundary of mountain forest and desert throughout the west. Lodgepole pine is perhaps its second favorite food (and its preferred species in the Sierra Nevada), but it will also forage readily on almost any soft-coned conifer and often shows up in surprising locations. Expect Type 2 as a common or abundant crossbill anywhere with mature conifer stands in the dry interior west and an occasional visitor to the wetter Pacific Coast Ranges and Northern Rockies.

Type 3 “Western Hemlock” Red Crossbill: Perhaps the most abundant North American crossbill within its range, Type 3 is a denizen of soft-coned conifer forests that grow under the misty auspices of the Pacific Ocean. Type 3s have the smallest bill of any North American crossbill, explaining why they are the only crossbill that will live and breed among the tiny cones of western hemlocks. However, they also love rich cone crops of Douglas-fir, spruces, mountain hemlock whenever they’re on the menu. Expect large to overwhelming numbers of Type 3s in the food-rich temperate rainforests and snow-forests of the Pacific Slope from sea level to treeline. They also sometimes irrupt into the interior west, where they will breed and forage among spruces and Douglas-firs.

Type 4 “Douglas-fir” Red Crossbill: Type 4 is a common but often unpredictable medium-billed crossbill prone to irrupting anywhere where cones are available. Douglas-fir is definitely a favorite but shares its top spot with a variety of other soft-coned conifers including Sitka and Engelmann spruces and western larch. Late in the cone cycle, some Type 4s may switch to hard-coned pines, especially in years with poor Doug-fir and spruce crops. They were recently even documented breeding in a pure ponderosa pine forest in Central Oregon. Expect this type to as a frequent visitor to rich food patches in the Rocky Mountains from Colorado north and to the Douglas-fir forests of the Pacific Slope, with a special concentration in the Puget Sound/Victoria Island regions where the Pacific subspecies of Douglas-fir is preferred over interior populations.

Type 5 “Lodgepole Pine” Red Crossbill: A medium-billed, mostly resident bird of the west’s most elevated highlands, Type 5’s relative scarcity and enigma mirror those of its preferred subalpine forest habitat. Lodgepole pine is certainly a key species for this population, but the relationship is somewhat complex. In years of plentiful Engelmann spruce cones, Type 5s prefer that species above all others, but in most years Engelmann cones tend to lose seed early and have unreliable cone crops. The hard, plated cones of lodgepole pine, in contrast, are serotinous (i.e. only open in response to fire or extreme heat) and hold seed for much longer, making them a critical fallback plan for the type in regular periods of scarcity. Expect this type as a regular and locally common crossbill in the Coloradan Rocky Mountains with a rare presence on the subalpine crests of the Northern Rocky Mountains, the Cascades, and the Sierra Nevada. Irruption over long distances or into unusual habitats is very rare but does occur.

Type 6 “Sierra Madre” Red Crossbill: Most of the west is dominated by vast swaths of a select few conifer species, but as the southern boundaries of the Rocky Mountains transition into the subtropical, monsoonal heights of the Madrean Sky Islands region in the American Southwest, a distinctive and diverse assemblage of conifers that dominate Mexico’s Sierra Madre highlands takes hold. These forests support the largest-billed Crossbill in North America, Type 6. The giant cones of the Apache Pine are one favorite food source. Due to a lack of documented foraging observations, it’s not well-known what other species Type 6 prefers, but Arizona Pine and Chihuahua Pine are other notable possibilities. Expect to encounter Type 6 from Arizona and New Mexico south in high-elevation pine-oak woods to Honduras.

Type 7 “Enigmatic” Red Crossbill: Unlike most of eastern North America, the western mountains contain enough rugged tracts of seldom-visited land that some populations and even species remain in obscurity. Type 7 is one of these remaining mysteries. A medium-billed crossbill which occurs very rarely in locations as widely separated as Oregon, New Mexico, Colorado, and Northern Alberta, no central zone of occurrence or preferred conifer has yet been definitively described for this type. At present, one notable hypothesis is that Type 7 could prefer non-serotinous populations of lodgepole pine north of the range of Type 5, in the Northern Rockies of Alberta, British Columbia, and the Yukon. We eagerly await more foraging data on this type.

Cassia Crossbill (formerly Type 9): Described as a type and later as a full species by crossbill researcher Craig Benkman’s team at the University of Wyoming, Cassia Crossbill has one of the largest bills and most specialized ecologies among North American crossbills. In the isolated forests of the South Hills of Idaho where they reside, Cassia Crossbills have apparently coevolved with a local lodgepole pine population that has developed large cone plates in the absence of their normal predator, red squirrels. Cassia Crossbill was recognized as a distinct species due to evidence of strong ecological and reproductive isolation from other crossbill types, facilitated by their narrow range and foraging preferences. However, Cassias have recently been showing up elsewhere in the west, breeding in Colorado and apparently visiting California and Wyoming, perhaps due to destructive wildfires in their normal range.

Type 10 “Sitka Spruce” Red Crossbill: A smaller medium-billed crossbill of the foggy Pacific Coast, Type 10 is another excellent example of a picky eater. Almost all known foraging observations of the type in the west are on Sitka spruce, which produces more reliable cone crops than many other soft-coned conifers. Despite occasional wanderings to the distant Northeast U.S., Type 10 rarely occurs in the west away from this tree’s narrow range, though it has occasionally been seen foraging on Douglas-fir and the shore subspecies of lodgepole pine in close proximity to Sitkas. Expect type 10 in a narrow band within 5-10 miles of the Pacific from northern California to southern British Columbia, with the inland range widening slightly to the north.

For the sake of the most dedicated crossbill-lovers, there are also two rare but notable eastern types which have occurred in the west:

Type 1 “Appalachian” Red Crossbill: Type 1 is a medium-billed type that uses red spruce and other mixed conifers across its preferred habitat in the far eastern quarter of North America. Nonetheless, a few birds rarely but regularly reach the coast of the Pacific Northwest in the winter, where they prefer a spruce with reliable crops, Sitka spruce.

Type 12 “Old Northeastern” Red Crossbill: Yet another medium-billed crossbill, Type 12s were only recently described and have a penchant for the red spruce, eastern white pine, and red pine forests of higher mountains in the northeastern US and Maritime Provinces. Type 12 records in the west are few and scattered, though it appears they could prefer the pine-rich woodlands of the interior west.

Know Crossbills By Knowing Cones

Crossbills will not just feed on any cone—cones must be ripe enough that the seeds are ready to eat, but not necessarily open enough that the seeds will fall to the ground. Birds prefer cones still attached to the tree but may feed from cones fallen to the ground if food is scarce. In this guide, we describe what conifers are available in the west, which crossbills prefer them, and how the different call types shift their diet through the crossbill cone cycle year.

Conifer trees in North America produce cones in a cycle that begins in May and June and start to ripen for crossbill consumption around the first of July. Crossbills will time one of their breeding cycles to match up with this time period when cone crops are developing and starting to ripen. If there’s enough available food on palatable trees, and this means even green cones (especially on spruces), then crossbills will begin breeding shortly thereafter, with this first breeding cycle extending from about July 1 to early September for the red crossbill call types and July 1 into October for the white-winged crossbill. The more pliable a conifer cone, the easier time a crossbill will have feeding on green cones.

Once the young have fledged, the birds will go looking for food stores once again if needed, but if the crop is “bumper” enough they can remain to nest again in the same area months later, even in winter when there’s feet of snow on the ground and sub-zero temperatures. If there’s not enough food, they’ll move on to the next available “rich patch” of conifers with accessible seed that will meet survival requirements, and hopefully another round of breeding. If there’s no food available on any of the trees in the area, they’ll “irrupt” en masse to travel further afield to find food. If they do find a large new food source, they’ll breed once again.

Birds have wings and minds of their own, so these rules aren’t hard-and-fast—and crossbills will also eat insects, lichen, deciduous tree seed, buds, and even seed from bird feeders in the absence of cones, especially in spring as temperatures begin to warm and food is depleted. But it takes a good cone crop to consistently support a breeding population.

So, if you want to find crossbills, you have to know your trees. Below we’ve compiled a list of conifer trees found in western North America (defined as all the area in the United States and Canada from the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains west to the Pacific Ocean) with notes on where the trees’ seeds sit on a crossbill’s preference list. We’ve also included a few other relevant trees that crossbills may visit during irruptions.

Conifers Preferred by Any Crossbill:

Common Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii)

Appearance: Tall and cylindrical, typically with a conical to uneven top and many large, sweeping, shaggy branches. Foliage variable in color, from yellow-green to emerald to blue-green. Short needles and dense, impenetrable appearance similar to spruces, but note less conical, sometimes round-topped form, more disorderly twigs which may be drooping or rigid. This is the tallest and largest tree on which crossbills typically forage anywhere on Earth, reaching heights over 300 feet and diameters of over 10 feet in the Pacific Coast rainforests.

Bark: Dark grayish brown to earthy reddish, usually deeply furrowed, sometimes covered in lichens and mosses

Leaves: Needles around 1 inch long, yellow-green to blue-green and paler below, growing either laterally from branch or in all directions

Cones: Reddish brown and conical, 3 inches long, with distinctive three-pointed bracts extending from behind the cone scales. Cones hang down from branches, like all the following trees except where specified otherwise.

Range and habitat: Widely distributed and abundant in forests with at least one wet or snowy season from central British Columbia (B.C.) to the Sierra Madre of Mexico. Douglas-fir is adaptable and fast-growing, making it North America’s favorite timber tree as well as ubiquitous in cultivated plantings and cities. Two distinctive subspecies are accepted:

“Pacific” Douglas-fir (P. m. menziesii) is often the most abundant tree throughout moist coastal forests from British Columbia to California, has deep green to yellow-green needles and bracts parallel to the cone scales. This population contains some of the most enormous and towering individual trees on Earth, and the prolific cones produces by old-growth and mature stands are preferred by any irruptive crossbill that encounters them.

“Rocky Mountains” Douglas-fir (P. m. glauca) is more sparsely distributed at high elevation in the Interior West and Sierra Madre. Needles are green to blue-green, and bracts are reflexed upward on the hanging cones. Tall, windswept individuals often occur alongside ponderosa pine, larch, and true firs at mid-elevation throughout the drier Western Cordillera. Type 4 uses this subspecies extensively, but it often doesn’t hold seed as long as the Pacific subspecies.

Tasting and Timing Notes: Douglas-fir is one of the two “universal super-snacks” that play the biggest role in driving western crossbill irruptions in years when cones are abundant. There are forests dominated by Douglas-fir across the contiguous western US and B.C., and it would be rare (if even possible) to spend a morning in one of these forests with a bumper cone crop without encountering crossbills. The cones are not just an option, but a favorite for all of our irruptive crossbills from the smallest-billed Type 3 to the large-billed Type 2, so finding your local mature patch or elevational band of Douglas-fir may be your best bet at finding crossbills.

Cones ripen in mid-summer to early fall and crossbills may start swarming unripe cones by early July. Despite fairly pliable scales, seeds typically endure well into the winter and early spring, regularly supporting winter breeding for multiple types.

Engelmann Spruce (Picea engelmannii):

Appearance: Typical orderly, dense, and conical shape of a boreal spruce. Sometimes pencil-thin in areas with heavy snowfall. Crown often comes to a sharp, rigid point. Color of healthy trees deep green to bluish green, often with distinctly glaucous tones. Twigs often drooping loosely from many curved, sweeping branches of even length producing an appearance somehow both shaggy and organized.

Bark: Grayish and covered in loosely attached scales, which woodpeckers often flake off to reveal rusty inner bark. Often coated with dense, pendant filaments of grayish-green lichen.

Leaves: Needles moderately short at around ¾ of an inch, glaucous to blue-green and four-sided, with sharp points.

Cones: Pale brown cylinders, averaging 2 ¼ inches long, scales thin and smooth with rough and irregular points. Cones shorter and stouter than other western spruces.

Range and Habitat: Widespread in western mountains but limited to high elevations with a true subalpine boreal climate. Most abundant in the Northern Rockies from central B.C. to Montana, Idaho, and Washington. Locally common in the highest elevations of the Rockies south to Arizona and New Mexico and in boggy or moist forests of the Washington and Oregon Cascades.

Tasting and Timing Notes: The second western “super-snack”, Engelmann spruce draws finch enthusiasts to some of the most remote, severely cold, and stunning beautiful locations in North America in search of crossbills. Similar to its eastern sister species white spruce (Picea glauca), the dense crops and pliable cone scales of this species are treasured by any crossbills that encounters them. The pockets of Engelmann spruces that often occur in wet or boggy habitats give rise to a characteristic experience: crossbills chattering overhead as they take flight across a picturesque alpine lake or meadow.

Cones follow a typical late summer ripening schedule. Nearly any Crossbill type may breed among Engelmann spruces in July-September. The soft cone scales generally release much of their seed by winter, but not enough to prevent regular winter breeding by White-winged Crossbills, which favor this tree above all others in the west. Among Red Crossbills, Types 3 and 5 seem especially fond of this spruce.

Note: “Hybrid” Spruce –Engelmann and white spruce readily hybridize where the two species meet in British Columbia, and it is a tree that all crossbills will use until the crop has dropped all its seed.

Sitka Spruce (Picea sitchensis)

Appearance: The Sitka is the largest of all the spruces and perhaps the most charismatic tree of the Pacific Northwest rainforest. The species generally has a broad and cylindrical overall structure with a pointed conical crown, making it recognizable as a spruce but distinctly fuller than its boreal cousins. Color is typically deep emerald to slightly grayish green. Many long, sweeping branches extend from the robust trunk. Younger branches toward the crown have twigs bushy and rigid while twigs of older, longer boughs droop nearly straight down, often leaving the bark of the limb naked above them.

Bark: Typically a cold metallic gray and heavily scaly, but sometimes appearing deep purply red when wet. Very often coated with diverse mosses and lichens.

Leaves: Needles just under an inch (average 7/8 in), two-sided with pale banding below and dark green above (unlike boreal spruces), tips sharply pointed

Cones: Pale brown oval/cylinders, average 3 inches, longer and with rougher, more pointed scales than Engelmann spruce

Range and habitat: Sitka spruce is a highly specialized obligate of the Pacific Northwest maritime fog belt, rarely growing more than 50 miles inland from the cold water of the ocean and its bays. This ever-soggy rainforest has some of the least variable temperatures in North America, rarely freezing hard in winter or breaking 70 degrees F in summer, creating a unique collision of boreal and warm temperate flora that stretches from the Humboldt Bay of California to the Gulf of Alaska. All of this region supports abundant Sitka spruce, though its range hugs the coast more narrowly at the northern and southern limits. In the north, it is reported to hybridize regularly with white spruce where the rainforest meets the taiga.

Tasting and Timing Notes: Like other spruces, Sitka spruce cones ripen in the late summer heat and are favorites with a wide variety of crossbills. What’s more, the stronger cone scales also hold plentiful seed into the winter, similar to red spruce (Picea rubens) in the east, and rarely experience range-wide failures. This has produced both one of the cleanest known cases of single-tree specialization among crossbills (Type 10) as well as some truly spectacular multi-type irruptions.

Type 10 red crossbills have such strong ties to Sitka spruce that they their calls are almost equally diagnostic coastal fog belt. There are only a few documented cases of type 10 straying away from these trees in the west, and they even choose its cone when more are available on Douglas-firs and western hemlocks nearby. However, Type 10s mysteriously become rare north of Vancouver Island, B.C. even where their favorite tree continues. Sitka spruce is also a favorite for any irruptive visitor to the coast. In one spectacular irruption in the winter of 2017-2018, Types 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10 and White-winged Crossbill were all recorded in Sitka spruces on the Oregon Coast, perhaps the most types attracted to a single tree in one irruption.

Blue Spruce (Picea pungens)

Appearance: Similar to Engelmann spruce in color (cone more similar to Norway Spruce), best separated by cones and needles. In general, blue spruce is more broad-based and has longer branches hanging toward the ground. The color does average brighter blue-green, but this isn’t always reliable in wild individuals.

Bark: Similar to Engelmann spruce, scaly grayish with reddish inner bark.

Leaves: Mid-length needles, average 1 in, generally more rigid and sharper points than Engelmann.

Cones: Slender pale brown cylinders, 3 in long, scales also longer and with more pointed tips.

Range and Habitat: The blue spruce is a fairly local tree in the wild, inhabiting lower mountain slopes in the central and southern Rocky Mountains, especially in canyons and near waterways. Its range extends from Idaho and Wyoming to southern New Mexico. The tree is much more familiar to many as one of North America’s favorite suburban lawn trees, including in several striking bright blue varieties.

Tasting and Timing Notes: Cones ripen in August, and papery scales likely allow most seed to fall in autumn. Like other spruces, seeds are universally accessible, so any type wandering through blue spruce woods is prone to use them. Specifically, Type 5s and, to a lesser degree, the other crossbill call types and White-winged Crossbills are known to forage on blue spruce when available.

White Spruce (Picea glauca)

Appearance: Conical or cylindrical, usually thinner in profile but denser in foliage than a red spruce, and thicker with more foliage than a black spruce, kind of a halfway between the two. Limbs don’t have quite the same upward-facing appearance and are less spaced out than those of a red spruce, giving it a scruffier, fuller, more cylindrical look. Ornamental white spruces typically appear shorter and more conical than wild white spruces, which can be rather imposing.

Bark: Pale gray-brown and scaly.

Leaves: Short, spiny, four-sided and pale-green growing directly from the branchlet, around ½ inch long.

Cones: Pale brown cylinders, 1 to 2 ½ inches long, which hang downward with thin, smooth scales. More elongated and thinner than red spruce and black spruce.

Range and habitat: White spruces grow across the boreal forest, from Alaska to Quebec and south to Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, and New England as far south as northern New York (it is a plantation tree in central NY), with an isolated patch in South Dakota’s Black Hills. White spruces have become a popular ornamental tree and appear in cemeteries, parks, yards, and other plantings.

Engelmann x White Spruce hybrids are also widespread where the two species meet in the Northern Rocky Mountains. Like both parent species, these trees are thought to be a crossbill favorite.

Tasting and Timing Notes: These trees are extremely well-suited for growing in the boreal forest, appearing further north than any other tree in North America, nearly to the Arctic Ocean. They’re also a favorite food of spruce budworm along with true firs. They have very pliable cone scales, and therefore will drop seed the earliest, often by the fall except in the best bumper crop cone years. During only the best white spruce bumper crop years can they remain in an area and nest into late February-early March.

This soft-coned conifer develops seed in summer and the cones ripen right away. Find yourself in an area with lots of cone-laden white spruce or hybrid spruce and you should definitely open your eyes and ears—these small cones are the most popular crossbill munchy for any crossbill that encounters them, especially the White-winged Crossbill.

Western Larch (Larix occidentalis)

Appearance: One of the most unmistakable western conifers: a tall, thin spire with a long, bare trunk topped by a small crown of verdant green in summer or bare twigs in winter. Similarly, this deciduous conifer is often recognized in the winter forests of the Northern Rockies when one notices that a large portion of the trees on a mountainside are “dead”. That is, until you take a closer look. Whether leafy or bare, this tree always has a slender, neat appearance, often punctuated by dense rows of its strawberry-sized dark cones.

Bark: Pine-like, with a plated and furrowed appearance, the plates silvery reddish and the grooves a deep gray.

Leaves: Average 1 ½ in, bright pale green, thin, and soft.

Cones: Deep brownish ovals held upright above branches, average 1 in long, bracts extending beyond scales as with Douglas-fir

Range and Habitat: The species is a distinctive feature of mid-elevation mesic forests in the Northern Rocky Mountains and leeward Cascades of southeast B.C., Idaho, Montana, Washington, and Oregon. It often forms large homogenous stands which are bright green in the summer and eerily bare in the winter. Note that a very similar species, subalpine larch (Larix lyalii) grows in high subalpine forests in roughly the same range, distinguished by its wooly twigs and smaller size.

Tasting and Timing Notes: Cones ripen late summer. Western larch cones are a happy medium, with cone scales not too large and not too small. This in theory should make them a crossbill favorite, but perhaps because of their limited and generally remote range, little is known about their relationships with crossbills. That said, Type 4 is known to forage readily on its cones and Type 3s often associate with larch forests in the interior west. The range of western larch is quite similar geographically to the area where Type 4s are most often recorded, so they may be more closely tied than is known. It was once thought that Type 7 might key in on it some as well.

Conifers Preferred by Small-billed Crossbills:

Western Hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla):

Appearance: Tall, thin, and cleanly conical, coming to a sharp point at the crown. Color is a deep emerald interspersed with the misty gray of lichens. Many short, shaggy branches with dense foliage protrude from the tree at all heights, the longer ones drooping to give the tree a bearded, wise appearance. Averages thinner and much more towering compared to related mountain hemlock. The leader branch on Western hemlock, mountain hemlock and Eastern hemlock all tilt one way or another; it’s a distinctive ID trait for hemlock at a distance.

Bark: Silvery brown outer bark with shallow vertical furrows.

Leaves: Tiny, at ½ in, deep green above and light below, extending perfectly straight to each side of the twig, creating a magical silvery appearance from below.

Cones: Minute brownish ovals, ¾ inch long and often very abundant, like thousands of tiny berries weighting down the branches.

Range and Habitat: Wherever the relentless Pacific rains keep the earth wet from October to May, you can find western hemlocks. This includes the Coast Ranges and Cascades from northern California to the Gulf of Alaska, as well as the wettest mid-elevation parts of the Northern Rockies in B.C., Idaho, and Montana. It is mostly sparser on the landscape than co-occurring trees like Douglas-fir and Sitka spruce, but this is largely because of logging and disturbance; western hemlock is a climax tree that is most abundant in old growth forests more than 200 years of age.

Tasting and Timing Notes: Cones ripen slightly later than associated trees, usually not until the start of September, though crossbills will use unripe cones as early as July. Despite tiny cones and flexible scales, the tree does continue to support foraging through the winter, though winter breeding in hemlock is rare. The only crossbill that normally makes use of this tree’s abundant tiny cones is Type 3, for which it is a favorite and a reliable predictor of irruption. At the few remaining coastal old growth sites, a bumper hemlock crop will often draw enormous flocks of many hundreds of Type 3s. White-winged Crossbill will also use the cones at least incidentally.

Mountain Hemlock (Tsuga mertensiana)

Appearance: Neatly conical, rising to a point at the crown which is often bent abruptly downward, making the whole tree look like an old wizard’s hat. Dense branches and deep emerald color similar to western hemlock, but mountain hemlock is almost always shorter.

Bark: Gray-plated, similar to western, though sometimes more deeply furrowed especially on older trees.

Leaves: Average ¾ in, deep green above and pale below, with undersides curving toward branch tip and looking like silver “stars” when viewed from the tip.

Cones: Medium pale brownish cylinders, average 2 in long, rounded scales. Appearance very similar to spruce cones, distinguished by always rounded scale edges, less papery scales. Unripe cones often deep reddish purple instead of green.

Range and Habitat: If western hemlock is the tree of the Pacific rainforest, then mountain hemlock is the tree of the Pacific snow-forest. The species is distributed on high-elevation mountains and rocky alpine slopes from the Gulf of Alaska to the Sierra Nevada of California and in the Northern Rockies of B.C., Idaho, and Montana. Its range essentially matches that of the very snowiest mountain peaks in North America, where oceanic storms often drop 10 to 15 feet of powder in a winter and the ground is still deeply buried in white come early May.

Tasting and Timing Notes: Cones ripen late, from late September to November, but birds readily use them by mid-August. Soft scales likely release most seed by partway through winter, but the species is poorly known compared to many other western conifers. This tree was recently documented as another favorite among Type 3s, which will rely on it for breeding in late summer. More research is needed to determine if other types use mountain hemlock, especially since Type 5 has sometimes been detected in forests dominated by this tree.

Black Spruce (Picea mariana)

Appearance: Thin, straight, and scruffy, often with needles concentrated at the top, giving it a truffula tree-like appearance.

Bark: Dark and brown, flaky.

Leaves: Short, spiny, four-sided dark green needles growing directly from the branchlet, ¼ to ½ inch long.

Cones: The smallest cones of North America’s spruces, ½ to 1 ½ inches long and squat, often spherical. Very round or barrel-shaped. Brown, thin scales. Concentrated toward the top. Cones are semi-serotinous, and therefore trees can hold cones, even with seed, for a couple years.

Range and habitat: Black spruces grow across the boreal forest, from Alaska to Newfoundland and south to the northeast U.S.. Can be found in a variety of areas, often in pure stands, though stereotypically form a core component of sphagnum bogs alongside tamarack.

Tasting and Timing Notes: Black spruce could be the arboreal mascot of the boreal forest and makes up a core component of sphagnum bogs and other cold-weather coniferous areas. These trees are a pioneer species, seeding right after fires and serving as the first trees to grow in bogs. Its cones are semi-serotinous, meaning some of their cones are encased in a jell and only open enough for seed to be accessible during the hottest heat waves or fire—this makes it so some trees hold seed most years, thus making it a key species utilized by White-winged Crossbills during the spring months when food becomes most limited. The core of its range is north of where most red crossbills are found, and so it isn’t utilized by red crossbills as much. It is susceptible to spruce budworm, but not as much as other conifer species. Crops form in spring but don’t really ripen until late winter and spring.

Tamarack (Larix laricina)

Appearance: Conical, occasionally quite triangular. In fall, they stand out against other conifers with their bright yellow needles, which they lose in the winter— like Western Larch, Tamaracks are deciduous conifers.

Bark: Flaky and gray to reddish brown as it ages, with deeper red-purple bark underneath.

Leaves: 1-inch spines, arranged in starbursts of 10-20. Bright green in summer, turning yellow in autumn.

Cones: Very small cones, wide and less than an inch long, giving them a rose-like appearance.

Range and habitat: Alaska, then east of the Canadian Rockies to Newfoundland and Labrador, south to the Great Lakes and the Northeast U.S. Often found in wet areas, such as alongside black spruce in sphagnum bogs and fens.

Tasting and Timing Notes: There are few boreal sights as striking as these deciduous conifers painting the forest yellow in the autumn. This soft-coned conifer develops seed in summer and cones ripen right away. Crossbills like it, especially white-winged crossbills in summer and fall who can easily access the tiny cones. Small and medium billed red crossbills (Type 1, 3, 10 and 12) utilize them, even occasionally for nesting, but this species isn’t a major player most years for red crossbills. Some northern areas contain pure stands of tamaracks, appearing like tree boneyards in the winter. Tamaracks serve as good habitat for boreal birds like spruce grouses, boreal chickadees, black-backed woodpeckers, and more.

Conifers Preferred by Large-billed Crossbills

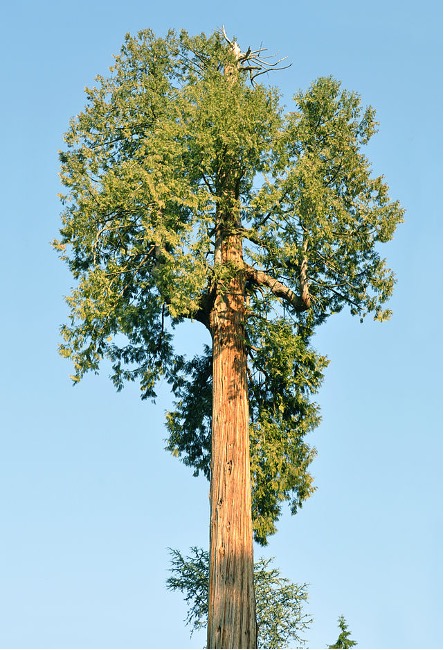

Ponderosa Pine (Pinus ponderosa):

Appearance: Tall and cylindrical, the reddish trunk generally bare to about a third of the way up the tree, topped by a series of moderately sparse branches ending in brushy puffs of long needles. Foliage color a sunny yellowish-green. Appearance unique among trees except for its closest relatives, Jeffrey pine (Pinus jeffreyi), Washoe pine (Pinus washoensis), and Arizona pine (Pinus arizonica).

Bark: Wonderful broad coppery-cinnamon plates punctuated by deep black furrows.

Leaves: Long needles in groups of 3, average 7 in, borne in large puffy clusters.

Cones: Large armor-plated reddish ovals, average 4 ½ in, each thick, hard scale with a sharp spine.

Range and Habitat: Very widespread and abundant on dry lower mountain slopes from southern B.C. to California, New Mexico, and the Sierra Madre in Mexico. Often found in vast, homogenous elevational stands which mark the broad boundary between montane forest and desert scrubland or grassland. The most widespread western conifer, ponderosa pines are a keystone species that provides critical habitat to a broad assemblage of ponderosa-obligate wildlife and plants, as well as at least one crossbill type. There are two important varieties of ponderosa pine:

“Rocky Mountains” Ponderosa Pines (P. p. ponderosa, scopulorum, and brachyptera), which stretch from the east slope to the Cascades throughout the interior west, have needles 3-6 inches in length in fascicles (groups wrapped in a sheath at the base) of 2-3. This is the variety frequented by Type 2 crossbills and occasionally other types.

“Pacific” Ponderosa Pine (P. p. benthamiana) present on coastal slopes and valleys from southwest B.C. to southern California, has even larger, harder cones than Rocky Mountains trees, longer needles (4-8 in) and apparently rarely attracts crossbills.

Tasting and Timing Notes: Large cones mature over 2 years, becoming ripe in midsummer the year after they are produced. Large scales retain seed over long periods, making this a rich resource. The large-billed Type 2 prefers and breeds in the Rocky Mountains forms of this tree most consistently, enough so that a coning ponderosa forest in the Interior West would scarcely feel complete without the rich, echoing calls of Type 2s overhead. Other crossbills were traditionally thought to shy away from these armored cones, but recent work suggests that ponderosa pine provides at least winter food for both Type 4 and occasionally Type 3. Type 4 was even recently found breeding among these trees in fall and winter!

Lodgepole Pine (Pinus contorta):

Appearance: Small, scruffy, and thin compared to other western conifers. Very straight stature, supporting a series of brushy, unkempt branches which curve upward to form a loosely conical top. Color is yellow-green to dull dark green.

Bark: Scaley and metallic grayish, with scales somewhat rougher and more protruding than on spruces.

Leaves: Short needles in groups of 2, average 2 ½ in, borne as brushy tips to branches

Cones: Small, plated brownish ovals, 1 ½ inches, each scale with a spine, serotinous in some populations

Range and Habitat: You might visualize the western mountains as coated in deep, shady evergreen woods, but visit these forests and you’ll find almost as many burn scars, lava flows, and clearcuts as pristine forests. Lodgepole pines are the shadow of this large-scale disturbance, sweeping in quickly to fill the empty space after fires and cuts with endless uniform groves of their straight trunks and scrawny-yet-scrappy boughs. The sister species of the boreal jack pine (Pinus banksiana), they grow rapidly in any mountain environment high enough to receive reliable winter snows or on sandy coastlines with mild maritime temperatures. Their range stretches from the southern Yukon and Northwest Territories south in the coastal mountains to the San Gabriels of California and along the crest of the Rockies to southern Colorado.

Regional variation in the lodgepole pine is of special importance to crossbills and their diversity.

Rocky Mountain lodgepole pine (P.c. latifolia), grows in montane habitat from southern Yukon to Colorado and often possesses serotinous cones. Within this subspecies, trees north of southern B.C. and Alberta are typically non-serotinous and trees in the South Hills of Idaho possess large cone scales evolved in the absence of red squirrels. This is a key population for Cassia Crossbills, as well as Type 5 and possibly Type 7 Red Crossbills.

Cascades/Sierra lodgepole pine (P.c. murrayana) grows on the snowy crests of the Oregon Cascades and Sierra Nevada and generally lacks serotinous cones. This population supports year-round foraging for Type 2s and rarely for opportunistic Type 4s and 5s.

Shore pine (P.c. contorta and bolanderi) grows on sandy beach soils from southeastern Alaska to central California, lacking serotinous cones and having a distinctly twisted or stunted shape, among several other differences from mountain lodgepoles. This unique population is rarely used by crossbills, but foraging by Type 10 has been observed.

Tasting and Timing Notes: Lodgepole pine presents a rich and geographically diverse food resource for any crossbill that will cut its bill on the armored cone scales. The combination of these hard scales and the serotinous cones of some populations makes it an especially reliable food source, often holding seed even in years when all other conifers fail. Lodgepole pine is a critical species for the survival of at least two crossbill populations. First, Type 5 Red Crossbills depend on serotinous Rocky Mountain lodgepole cones in periods of food scarcity. Expect Type 5s in Colorado and Wyoming where this tree overlaps with Engelmann spruce, their other favorite food. Second, Cassia Crossbills are forage on the unique large-coned variety of lodgepole in their restricted range in the South Hills and Albion Mountains of Idaho, though their habitat in this area may be critically threatened by severe wildfires.

Other crossbills that use this tree include Type 2, which is especially fond of the Cascades/Sierra variety that provides its main food source in the California, and possibly the mysterious Type 7, which could potentially be connected to the northern variety of Rocky Mountain lodgepole. What’s more, Type 4s and even Type 3s are known to switch to lodgepole cones when stores of other conifer seeds dwindle in the late winter and spring. Even the specialist Type 10 has been documented snacking on shore pine seeds, underscoring this tree’s broad appeal.

Apache Pine (Pinus engelmannii):

Appearance: Mid-sized pine with irregular branches coalescing into rounded crown. Very straight stature. Branches sparse but filled out by many broad puffs of very long, sunny green needles borne at branch ends.

Bark: Similar to ponderosa pine, in large reddish plates with comparatively shallow dark furrows.

Leaves: Extremely long needles in groups of 3, average 13 in, deep green and drooping.

Cones: Slender, lopsided deep brown ovals, 5 in long, scales held tightly together with pointed tips protruding to side.

Range and Habitat: This tree is an inhabitant of the Madrean Sky Islands of southeastern Arizona, stretching south through the Sierra Madre Occidental of Mexico to Nayarit and Zacatecas. Isolated patches exist near Mexico City. Generally found on dry ridges and mountain slopes, often in the company of oaks.

Tasting and Timing notes: Cones mature after two years and begin releasing seeds in November or December. Sturdy, armor-plated cones likely make this a persistent reservoir of seed for many months. This tree is a noted favorite of Type 6, which has evolved a very large bill to access its seeds and that of other hard-coned pines. Its large scales would make foraging difficult for almost any other type, though Type 2 could probably make successful attempts.

Trees Occasionally Used by Crossbills (especially Type 2)

Western White Pine (Pinus monticola):

Identification: Distinguished from other pines by needles in groups of five, cones long but not extremely long (5-10 in), bark deep ashy charcoal color in large, ‘dragon-scale’ plates. Trees very tall (often over 100 ft), frequently towering over surrounding forest.

Range, Habitat and Crossbills: Western white pine is a widespread but uncommon tree in high mountain forests from southern B.C. to Idaho and the southern Sierra Nevada of California. Its sister species, eastern white pine (Pinus strobus) is one of the most important food sources for crossbills in the Northeast, so it seems almost certain that crossbills forage on this tree at least occasionally. That said, it is generally very sparse on the landscape in the Cascades and Sierras, so there may simply be insufficient cones to provide a meaningful food source. Type 2 has been noted utilizing it in Wyoming whenever crops are good (personal communication Zach Hutchinson) . It is slightly more abundant in the Northern Rockies, where foraging by Type 4 would be expected.

Sugar Pine (Pinus lambertiana):

Identification: Longest cones of any conifer (10-20 in). Otherwise very similar to western white pine. Bark is in coppery plates separated by deep furrows. Overall appearance of majestic tall pine with reddish trunk and very long, sweeping branches weighted at tips by enormous cones is distinctive.

Range, Habitat, and Crossbills: The charismatic, larger-than-life cones of this species are a distinctive marker of the Californian mid-elevation conifer forests. Can be found isolated or in large stands on mountain slopes from Central Oregon south to northern Baja California, Mexico. Despite their enormity, the cones have pliable scales that should be accessible for the Type 2s, 5s, and 4s that frequent the tree’s range, and Type 2 has been documented using the tree, including for breeding, in Southern California.

Jeffrey Pine (Pinus jeffreyi)

Identification: Very similar to ponderosa pine. Primary difference is slightly larger cones (average 9 inches but variable) and minute details of cones, along with a sweeter scent to the bark and wood.

Range, Habitat, and Crossbills: Jeffrey pine grows in the montane Californian ecoregion from southwest Oregon to northern Baja California. Jeffrey pine commonly grows from mid to high elevation in areas with a serpentine soil chemistry, which often produces a unique rocky savannah-like environment. Cones are perhaps a bit large for easy access, but Type 2s have been documented using it as a foraging tree, including for breeding, in Southern California.

Pinyon Pines (6 species):

Identification: Needles short (1-1 ½ in) in groups of 1-3. Cones tiny (1 ¾ in) and round. Trees short and brushy. Range, Habitat, and Crossbills: Dry desert slopes from the northern Sierra Nevada to Colorado south to Baja California, central Mexico, and the Big Bend region of Texas. Habitat and large seeds may deter most crossbills, but Type 2s are known to feast on them abundantly during bumper crops (personal communication Brian Maxfield). Also used extensively by seed-eaters such as the pinyon jay (Gymnorhinus cyanocephalus

True Firs (Abies, 9 species):

Identification: True firs are distinguished from other North American conifers by their long cones held upright from the branches that break apart scale-by-scale when ripe instead of opening and falling intact, as well as waxy needles which attach to the branch with a round, cup-shaped joint. Their narrow conical shape with rigid, organized branches are also largely unique, though boreal spruces may approximate the same shape. Otherwise, the west’s firs are very diverse, from the shiny, emerald green grand fir (Abies grandis) of the lowlands to the pencil-thin boreal spires of the subalpine fir (Abies lasciocarpa) to the robust, lustrous blue-green towers of the noble fir (Abies procera) which adorn the northwest coastal mountains.

Range, Habitat, and Crossbills: The western firs range from southwest Alaska to the Upper Liard Valley of the Yukon south to the central California coast and New Mexico. Other species are found in Mexico south to Central America. Habitats vary, but firs generally prefer forest with abundant moisture and shade over dry environments and are often forest climax species. Because of their flaky cones that release all seed early in the fall, they are not a reliable food source for crossbills, but they are used from time to time. Moreover, they are a favorite among several other species of finches, including irruptive Pine Grosbeaks (Pinicola enucleator) and the threatened Evening Grosbeak (Coccothraustes vespertinus).

Western Redcedar (Thuja plicata):

Identification: Foliage in flattened sprays of smooth, scaly leaves, not needles. Cones are tiny (1/3 in) and brown with layered scales, almost flower-like in appearance. Trees are tall to very tall (60-200 feet or more), with gorgeous soft, cinnamon-colored bark with many parallel furrow-lines. Shape is tall, thin, and conical with foliage organized in beautiful fan-like structures. If you’re coming from eastern North America, note that this tree is more closely related to northern white-cedar (Thuja occidentalis) than eastern redcedar (Juniperus virginiana).

Range, Habitat, and Crossbills: Western redcedar is a magnificent tree of the densest, shadiest, and wettest parts of the northwest rainforest. Found in the coastal mountains from far southeast Alaska to northern California and in the Rockies from central B.C. to Idaho. Crossbills may use this tree occasionally, but it is much more popular with Pine Siskins. That said, if you encounter western redcedar, good crossbill habitat in the form of hemlocks, Doug-firs, and spruces is usually present nearby.

Limber Pine (Pinus flexilis)

Identification: From other white pines by short needles (2 ¼ in) and cones (5 in), bark whitish on young trees and scaly like lodgepole pine on older trees. Often stunted (height of 35-50 feet) and brushy in appearance due to habitat.

Range, Habitat, and Crossbills: Limber pine grows where virtually no other conifers will, atop the highest rocky crags and on steep, bone-dry slopes and lava flows. It can be found in these harsh habitats from southern B.C. and Alberta south to California and northern Sonora, Mexico. Flexible scales and perfect-sized cones make this species seem an excellent candidate for a crossbill delicacy, but perhaps its unusual habitat and generally stunted size prevent it from becoming a favorite.

Southwestern White Pine (Pinus storbiformis)

Identification: Similar to limber pine. Longer cones (8 in) with scales bent backwards and longer needles on average (3 ½ in). Taller on average (60-80 feet or more).

Range, Habitat, and Crossbills: Grows in much moister forest than limber pine. Found in higher mountains from southern Colorado through the northern Sierra Madre of Mexico. Cones should be suitable for use by crossbills, with Type 2 and Type 6 being potential foragers based on range

Whitebark Pine (Pinus albicaulis)

Identification: From other white pines by short needles (2 ½ in) and small, oval, tightly closed cones (2 ½ in long). Typically stunted (15-30 feet tall) and with whitish bark. Sometimes similar to lodgepole pine, but see needles in clusters of 5 and details of cones.

Range, Habitat, and Crossbills: This tree grows at the border of forest and alpine tundra, inhabiting some of the snowiest, windiest, and coldest habitats in North America. Range stretches from the Northern Rockies and Coast Ranges in B.C. and Alberta south to Wyoming and the Sierra Nevada. The unforgiving environment and their closed cones make these trees perhaps unsuitable for crossbills in general, but they are the critical food sources of Clark’s Nutcrackers (Nucifraga Columbiana), so may have some viability when crossbills are in great need.

Scots Pine (Pinus sylvestris)

Identification: Small tree (25-50 feet tall) with bark a distinctive clay red to gray and furrowed. Cones small (2 in) somewhat like lodgepole pine. Needles in groups of 2.

Range, Habitat, and Crossbills: This tree is introduced from Eurasia and often escaped in lowland valleys in the west, especially near the Pacific Coast. The cones are suitable for crossbill foraging in the east, so this likely represents an occasional supplemental food in the west as well.

Arizona Pine (Pinus arizonica)

Identification: Very similar to ponderosa pine and once considered a subspecies. Differs in needles in groups of 4 or 5 and short cones (2 ½ inches).

Range, Habitat, and Crossbills: Range-restricted to the Madrean Sky Islands of Arizona and New Mexico, where summer monsoons sustain distinctive subtropical flora. This tree is a likely secondary food source for northern Type 6s.

Chihuahuan Pine (Pinus leiophylla)

Identification: Unique among North American yellow pines (meaning the ponderosa and lodgepole group) in several respects. Needles (3 in long) are in groups of three without the needle sheath at the base that most yellow pines share. Cones are very small and rounded, maturing in three years instead of the typical two. Generally short (35-50 feet tall) with grayish to reddish bark in plates.

Range, Habitat, and Crossbills: From the Sky Islands of Arizona and New Mexico south in the Sierra Madre Occidental to the Mexico City area. Found on dry montane slopes, often in the company of oaks. This tree is a prime candidate for an important Type 6 food source, with its likely accessible seeds and broad range in similar habitat to Apache pine.

Knobcone Pine (Pinus attenuata)

Identification: Needles in groups of 3. From other yellow pines by long cones with spiky plates that remain tightly closed at maturity, dark purplish-brown bark. From pines of coastal California by cone length and long prickles, warm tones to bark

Range, Habitat, and Crossbills: Knobcone pine is a conifer of the fire-shaped landscapes that once dominated low to mid-elevation California. Its range extends from southwest Oregon to northern Baja California in low-elevation dry forest, typically among other pines or with oaks. Its highly serotinous cones would normally be inaccessible to crossbills, but after the fires which are growing more frequent in the region they may open, perhaps providing an unpredictable but notable seed source.

Subalpine Larch (Larix lyallii)

Identification: Very similar to western larch. Distinguished only by wooly twigs, somewhat shorter needles (1 ¼ vs. 1 ½ inches). Stature typically stunted due to habitat.

Range, Habitat, and Crossbills: Occurs near timberline in the North Cascades of Washington and the Northern Rockies of B.C., Alberta, Idaho, and Montana. Another tree of harsh alpine habitat, crossbills probably rarely come into contact with subalpine larch, but when they do its nearly identical cones surely provide a food source similar to western larch.

Red Alder (Alnus rubra), alders (4 species), and birches (Betula, 4 species):

Identification: The alders and birches are two related genera of widespread and abundant boreal deciduous trees. They share smooth whitish, grayish, or reddish bark with darker knots or spots interspersed, simple oval leaves with serrated edges, and unique fruit the resembles very small conifer cones. Red alder is the only wild growing tree in this group in the west south of the boreal forest, told from other local trees by its whitish-gray bark, oval leaves, and tiny “cones”. Paper Birch (Betula papyrifera) grows in boreal areas of the Northern Rockies and is told by its unique peeling bark. European weeping birch (Betula pendula) is a common tree in suburbs, distinguished by its white bark with black knots and drooping twigs. See our companion article on the east for discussion of boreal birches and alders.

Range, Habitat, and Crossbills: Our birches and alders occur from the shore of the Arctic Ocean in Alaska across the boreal forest to the eastern US. In the west, they occur south to Southern California, the northern Sierra Madre, and New Mexico. Habitat is variable but most species prefer wet soils in very moist mountains or in alpine bogs and meadows. They aren’t a crossbill’s first choice, but birds have been observed foraging on them several times nonetheless. These trees are a favorite food of Pine Siskins (Spinus pinus) and Redpolls (Acanthis flammea).

Sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua)

Identification: Unmistakable broadleaf deciduous tree with star-shaped leaves and 1-inch spiky balls for fruit. Bark is a furrowed silvery gray. Grows tall and straight, with many long side branches of similar size meeting in a single long trunk. Fall color is a spectacular display of yellow, orange, red, and purple.

Range, Habitat, and Crossbills: This charismatic deciduous tree is native to the eastern hardwood forests of North America, but it is among the most common street trees in the milder coastal parts of the west. Crossbills are known to forage on the fruit, which ripen in the fall and are a frequent sight in older suburbs, college campuses, and parks. Sweetgum is also partially included here to note that there are a plethora of other broadleaf trees which may occasionally draw the interest of crossbills, but these relationships are often poorly documented.

Cover photo credit of Type 2 Red Crossbill on Blue Spruce April 2019, Michael O’Brien

Book Link

For help with Finch ID and much much more, here is a link to the exciting and newly released Stokes Guide to Finches of the United States and Canada: https://www.amazon.com/Stokes-Finches-United-States-Canada/dp/0316419931

The Finch Research Network (FiRN) is a nonprofit, and was granted 501c3 status in 2020. We are a co-lead on the International Evening Grosbeak Road to Recovery Project, and have funded $22,000+ to go towards research, conservation and education for finch projects in the last couple years. FiRN is committed to researching and protecting these birds like the Evening Grosbeak, Purple Finch, Crossbills, Rosy-finches, and Hawaii’s finches the honeycreepers.

If you have been enjoying all the finch forecasts, blogs and identifying of Evening Grosbeak and Red Crossbill call types (20,000+ recordings listened to and identified), redpoll subspecies and green morph Pine Siskins FiRN has helped with over the years, please think about supporting our efforts and making a small donation at the donate link below. The Evening Grosbeak Project is in need of continued funding to help keep it going.

Donate – FINCH RESEARCH NETWORK (finchnetwork.org)

Please think about joining Finch Research Network iNaturalist Projects:

Winter Finch Food Assessment Project/Become a Finch Forecaster: https://finchnetwork.org/the-finch-food-assessment-become-a-finch-forecaster

Red Crossbill North American Foraging Project: https://finchnetwork.org/crossbill-foraging-project

Evening Grosbeak North American Foraging Project: https://finchnetwork.org/evening-grosbeak-foraging-project

Filed Under: Uncategorized Tagged With: #finches, #finchnetwork, #finchresearchnetwork, #irruptions, Evening Grosbeaks

Works Referenced:

https://finchnetwork.org/a-crossbills-guide-to-conifers-of-the-northeastern-forest

Sibley, D. 2009. The Sibley Guide to Trees, in print.

USFS Southern Research Station Profiles on Conifers (Douglas-fir, western hemlock, etc.) https://research.fs.usda.gov/srs

https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/misc/ag_654/volume_1/pseudotsuga/menziesii.htm

https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/misc/ag_654/volume_1/picea/engelmannii.htm

https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/misc/ag_654/volume_1/tsuga/heterophylla.htm

http://floranorthamerica.org/Main_Page

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pinus_leiophylla

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pinus_engelmannii

https://www.inaturalist.org/observations

Groth, J. G. 1993. “Call Matching and Positive Assortative Mating in Crossbills.” The Auk, vol. 110, no. 2. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4088572

Benkman, C. W., Parchman, T. L., Favis, A. Siepielski, A. M. 2003. “Reciprocal Selection Causes a Coevolutionary Arms Race between Crossbills and Lodgepole Pine”. The American Naturalist, vol. 162, no. 2. https://doi.org/10.1086/376580

Szeliga, W., Benner, L., Garrett, J., & Ellsworth, K. 2014. Call types of the Red Crossbill in the San Gabriel, San Bernardino, and San Jacinto Mountains, southern California. Western Birds, 45, 213–223.

Morton, J. M., Wolf, D. E., Bowser, M. L., Takebayashi, N., and Magness, D. R. 2023. The dynamics of a changing Lutz spruce (Picea × lutzii) hybrid zone on the Kenai Peninsula, Alaska. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, vol. 53, pp. 365-378. https://cdnsciencepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1139/cjfr-2022-0212

Hutchinson, Zach. Pers. Communication.

Maxfield, Brian. Pers. Communication.

Photo Attributions:

- Wikimedia Commons user Walter Siegmund, Pseudotsuga menziesii, CC BY SA 3.0.

- Wikimedia Commons user Walter Siegmund, Pseudotsuga menziesii, CC BY 2.5.

- Wikimedia Commons user Walter Siegmund, Pseudotsuga menziesii, CC BY 2.5.

- Wikimedia Commons user jsayre64, Picea engelmannii, CC BYSA 3.0.

- Wikimedia Commons user Matt Lavin, Picea engelmannii, CC BYSA 2.0.

- Wikimedia Commons user Walter Siegmund, Picea engelmannii, CC BYSA 3.0.

- Wikimedia Commons user Graaf van Vlaanderen, Picea sitchensis, CC BYSA 4.0.

- Bureau of Land Management Oregon and Washington, Picea sitchensis, CC BY 2.0.

- Wikimedia Commons user Kimon Berlin, Picea sitchensis, CC BYSA 2.0.

- Wikimedia Commons user Dave Powell, Picea pungens, Public Domain.

- Matthew Young, Picea pungens.

- USDA Forest Service – Region 2 – Rocky Mountain Region, Picea pungens, CC BY 3.0.

- Wikimedia Commons user dmcdevit, Picea glauca, CC BYSA 2.0.

- Matthew Young, Picea glauca.

- Wikimedia Commons user Walter Siegmund, Larix occidentalis, CC BY 2.5.

- Wikimedia Commons user Thayne Tuason, Larix occidentalis, CC BYSA 4.0.

- Wikimedia Commons user hojaleaf on Flickr, Larix occidentalis, CC BY 2.0.

- Wikimedia Commons user Doug Kerr, Tsuga heterophylla, CC BYSA 2.0.

- Wikimedia Commons user Peter Stevens, Tsuga heterophylla, CC BY 2.0.

- Wikimedia Commons user Walter Siegmund, Tsuga mertensiana, CC BYSA 3.0.

- Wikimedia Commons user Walter Siegmund, Tsuga mertensiana, CC BYSA 3.0.

- Matthew Young, Picea mariana.

- Matthew Young, Picea mariana

- Matthew Young, Larix laricina.

- Wikimedia Commons user Tim & Selena Middleton, Larix laricina, no longer available.

- Wikimedia Commons user calebcatto, Pinus ponderosa, CC BY 4.0.

- Wikimedia Commons user Mitch, Pinus ponderosa, CC BYSA 2.0.

- Wikimedia Commons user stereogab, Pinus contorta, CC BYSA 2.0.

- Wikimedia Commons user Jim Morefield, Pinus contorta, CC BYSA 2.0.

- Wikimedia Commons user Walter Siegmund, Pinus contorta, CC BY 2.5.

- Wikimedia Commons user Chris M, Pinus engelmannii, CC BY 2.0.

- Wikimedia Commons user Kretyen at Flickr, Pinus engelmannii, CC BY 2.0.

- Richard Sniezko, US Forest Service Dorena Genetic Resource Center, Pinus monticola, Public Domain.

- Wikimedia Commons user Mitch Barrie, Pinus lambertiana, CC BYSA 2.0.

- Wikimedia Commons user Ewen Roberts, Pinus jeffreyi, CC BY 2.0.

- Wikimedia Commons user Adam Baker, Pinus cembroides, CC BY 2.0.

- Wikimedia Commons user Šarūnas Burdulis, Abies procera, CC BYSA 2.0.

- Wikimedia Commons user abdallahh, Thuja plicata, CC BY 2.0.