Crossbills of North America: Species and Red Crossbill Call Types:

By Matthew Young, Tim Spahr and Caleb Centanni 2025:

This document contains information on Crossbills present in North America, including the Red Crossbill, Cassia Crossbill, White-winged Crossbill, and Hispaniolan Crossbill. The Red Crossbill complex is known to have many “flight call types”, that also show small differences in genetics, morphology and core zone of occurrence, the area where each type is most common and uses a unique, but often overlapping, suite of conifers. For more about this complex please see the newly released Stokes Guide to Finches of the United States and Canada.

Matt wrote the first primer back in 2008 followed by another in 2012, Tim joined the team for the one in 2017, and now Caleb is joining us for this one that is a bit overdue. When crossbills were on the move in 2012, we were pleased to author a full-length featured article for eBird by Matt Young, one of the North America’s experts on this incredibly complicated species complex. Tim Spahr joined the team back then and has also become an expert in “typing” crossbill recordings. Tim has made several trips across the North America to get a better handle on several of the types. He also has been traveling around portions of the northeast to help us get a better handle on what types were breeding the past decade or more. Caleb is a PhD student at Cornell University researching the call type phenomenon across finches and has studied crossbill type ecology in the conifer-rich mountains of Western Oregon. He published a paper on the topic last year.

We’re providing this summary, which includes the addition of Type 12, as mainly a revision of the 2017 article – This article also provides the latest updated information on all the types. With the loss of Cassia as a call type (was formerly Type 9) and gain of Type 12, Red Crossbills still have eleven distinct call types in North America, each with its own key conifer(s), areas of core occurrence, and patterns of movement.

INTRODUCTION

Red Crossbills (Loxia curvirostra) represent an ecological puzzle for biologists and birders alike, and an opportunity for pioneering citizen-science driven fieldwork for those inclined to explore some of North America’s little-birded coniferous habitats. Since Jeff Groth’s landmark work in 1993, the value of recording crossbills for identification to type has become increasingly recognized. Groth’s work laid out the idea that each taxon gives a unique, identifiable call type when in flight. As stated, as many as eleven “call types” of Red Crossbill can be found across North America (Groth 1993, Benkman 1999, Irwin 2010, Young et al. 2024), each of which may represent a different incipient species (Parchman et al. 2006). The flight calls given by an individual bird have been confirmed to be relatively stable over time (Sewall 2009, Sewall 2010). These call types have also been shown to correspond with slight differences in vocalizations, morphology, genetics, and ecological associations (Groth 1993, Benkman 1993a, Parchman et al. 2006, Young et al. 2024). In 2017, after several years of research by Dr. Craig Benkman and his team, “South Hills Type 9”, was elevated to the species level as Cassia Crossbill (Loxia sinesciurus) – named for one of the two counties in Idaho where the species occurs. As stated above, Type 12, which has existed for decades, was just formerly described in the last year as well.

Variations, Modifications and Intermediates

As with any complex bird identification, it’s important to have a solid grasp on the possible variation within a given call type before making a determination. The thought is that the very first vocalizations that crossbills hear as nestlings are those of the flight calls of their parents. Flight calls (like the territorial songs of most songbirds) are thought to be learned by juveniles during their first couple months of life, but you can expect young birds to sometimes produce confusing calls before learning is complete (Sewall, 2009). You can also expect to hear variation in adult birds of the same type, especially if you visit different areas of their breeding range (see ‘kinked’ and ‘unkinked’ Type 2). What’s more, adults, especially after successful breeding, can modify their call to match that of a mate on the breeding grounds! Fortunately for those us trying to identify types, their flight call is generally thought to be a reliable signal of a bird’s origin population (Sewall 2009, Sewall 2010), and it is quite rare for birds to switch to a different call type (Keenan et al. 2008).

With the above said, this period of call matching can lead to variation (i.e. variants) in the flight call structure of a given flight call. If one were to assess each of these modifications as new call types, too many call types could be classified and therefore described, so it’s important that there is a good representative sample of recordings across the year, including outside breeding periods, before flight calls are sorted and described as new. It is also important that many recordings, from the same population (which preferably would include some banded or tagged birds), across several years are obtained, before any kind of call evolution is described. Without some tagged or banded birds, and/or fairly complete knowledge of crossbill movements on a continent-wide scale, the description of any call type evolution would seem dubious.

When certain types infrequently come in contact with one another, like when Types 2 and 3 come in contact in interior areas, or when types 4 and 10 come in contact along west coast, or when types 1 and 12 come in contact in the Northeast, birds seem to show the ability to modify their calls to a moderate degree, thus resulting in recordings looking and sounding somewhat intermediate. Again, these birds are rare overall, but as we’ve been quoted before, there are upwards of 5% the total number recordings that are best left unidentified at the call-type level. The number of intermediates might be a touch higher in the east and this is an area in need of more research. For examples of intermediate flights calls, please see the end of this primer.

Other Vocalizations: Excitement Calls, Chitters, Chittoos, and Songs

In addition to flight calls, the adult Red Crossbill’s repertoire includes excitement calls, chitter calls, and songs. Excitement and chitter calls make up a very small fraction of vocalizations a crossbill will give across a year, so they are pretty uncommon maybe making up 5-10% of what you might hear while doing field work in a given area. Excitement calls, also known as “toop” calls, are typically used in non-flight social contexts, especially at breeding sites or in alarm. They can be a good bit more common when they are breeding, but can be pretty rare outside of breeding. Excitement calls can aid in identification for some call types, but others overlap and are very hard to conclusively separate to an ID. Chitter calls are soft, variable vocalizations given when flocks are foraging, drinking or resting and are not known to be distinctive to type as well. It is also possible to mistakenly classify chitters as new flight calls, but with practice, this is also relatively easy to avoid. It is not uncommon to hear birds giving chitter calls, which are softer than true flight calls, begin to rise in volume and take better form.

Red Crossbill songs are impressively complex and variable. They currently cannot be used for identification to call type, though we expect that some differences exist, especially in tonal quality and the different phrases they use. It’s important to remember that the song of the Red Crossbill is made up of call notes, buzzy notes, warbles and whistles, and that a recording can have lots of perceived “flight calls” in it but if there are warbles, whistles and buzzy notes interspersed that identifying the recording to a call type can’t be trusted — When people send us recordings like this, we’ll always respond that it sounds like song, and its best to leave this as Red Crossbill. This is also why it’s important to make sure you get a long enough clip so we can rule out song.

Juvenile Crossbills also produce two-syllable, nasal “chit-too” calls that are uniform across types, these are only given in the first 4-8 weeks of their life. We link to examples of some of these just below and for excitement calls of Types 2, 4 and 6 in the call type section of this primer. In order to stay focused on the best traits to identify birds to call type, everyone should concentrate on learning the flight calls!

Chitoos: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/68287351

Monotypic Type 12 flock giving flight calls, chitters and toops: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/295818071

Crossbill Strategies

When you obtain audio recordings, we also encourage you to record the foraging behavior of the birds you documented. Each type may specialize on a unique conifer or set of conifers, but how consistently they specialize on a single tree species is still a matter of debate (Benkman, 2003; Martin, 2019; Centanni, 2024, Stokes and Young 2024). Red Crossbill call types seem to conifer switch to find the species they can most easily forage on at that time, as this paper by Craig Benkman highlights nicely. The recently described Type 12 shows this behavior consistently — The Information collected here by Matt Young and team, and here by Cody Porter, strongly supports what has been known now for the better part of the last decade or more. Crossbills are constantly assessing food crops, and they’re looking for that next rich patch of conifer seeds to most easily feed on. Some of the types are much more nomadic and do this on a continent-wide scale.

There are some that do appear to more dialed into a single key conifer (types 5, 9/Cassia and likely 10 on the west coast), while others are more nomadic and assess which conifers to switch to on a continent-wide scale (2, 3, 4), and some do this on a more localized or regional scale (types 1 and 12). We need more studies on types 6, 7, 8 and 11 to know what strategy they most readily use.

Understanding the most important food sources for each type will help people find crossbills, help us predict irruptions, and may prove critical if conservation efforts are necessary like with Cassia Crossbill (Type 9). To record a Crossbill foraging observation, you can upload both a recording and an image of the recorded bird foraging into your eBird checklist, or you can contribute to Finch Research Network’s Crossbill Foraging iNaturalist project. Cody Porter also has a crossbill foraging project linked here.

DOCUMENTING AND RECORDING CROSSBILL CALLS

We encourage anyone encountering crossbills to attempt audio recordings. While we welcome recordings from those with professional grade recording equipment, even smartphones can adequately document the call types. It is always better to download a sound recording app that makes .WAV files, which prevent loss of important audio information. However, even using the “voice memo” feature can get a decent recording that can help to type the crossbill. For example, on an iPhone just open your audio recording app, hit record, hold your phone as steadily as possible with the speaker facing the crossbill, and then email the recording for analysis along with a link to your eBird checklist! External microphones can be purchased that improve the recording quality even more; check out recommendations from the Macaulay Library.

It should be noted that there is great variability in recording quality, and some recordings may simply not have enough information to make a determination to flight call type. Similarly, the highest-quality recordings can often have absolutely bewildering structure at the finest resolution. High-quality microphones, portable parabolic dishes and 32-bit recording have definitely changed the landscape. In some cases recordings are so good, and show so much structure, that flight call types can be a bit hard to identify.

If you record a Red Crossbill, please enter it as “Red Crossbill” in eBird, upload the recording to your checklist, and send the link to the checklist to Matt, Tim or Caleb (for the west) for assistance with identification to specific call type. If identification to Type can be confirmed via the recording, you can easily use the “Change Species” feature to search for the correct crossbill type and revise the identification. If you try to identify the type yourself, do not worry if you misidentify the proper call type; one of the authors will likely try to contact you after listening to your recording. Keep in mind many crossbills can be typed from very poor recordings, so we’ll do our best to help. With that said, it has been a labor of love, and Tim and Matt at FiRN are hopeful that an automated call recognizer is around the corner that will help ease the workload. Stay tuned for more on that. But seriously, without you, the knowledge accumulated around crossbill vocalizations, distributions, and foraging habits would not be possible. Amazingly, there are now almost 33,000 Red Crossbill recordings in the Macaulay Library, which is the most of any species in the collection! The next closest is Carolina Wren at around 24,000 recordings.

To identify Red Crossbills to call type one needs to do an audiospectrographic analysis. Raven Lite (and Audacity or Adobe Audition) can be used for this work. This analysis gives a computer printout of the bird’s voice and therefore represents a signature of the call type. Briefly, this printout shows the frequency of the sound in kilohertz on the “y” axis and time from the beginning of the recording on the “x” axis. It is important that everyone set the limits on the “y” axis to around 10,000 kHz and have the “x”-axis window (or scale) be around 1 second. When one analyzes crossbill spectrograms, the scale needs to be consistent, and we would emphasize that the larger the scale the better, since using too fine of a scale can lead to missing certain intricacies of a given call type.

In a departure from previous recommendations, we are requesting birders simply upload media to eBird checklists and email us the checklist for type-specific identifications. Please do not email us individual sound files. As mentioned above, in the reasonably near future we expect to have machine learning/AI -assisted type determination that will hopefully help make the process a bit more manageable for us here at the Finch Research Network.

Please note that additional Types occur in Europe, Africa, and Asia, and that we welcome insight into that puzzle as well. Please write to either Matt or Tim or Patrick Franke if you are interested in contributing to future work that addresses crossbills at a global level. And on that note, we are interested in ramping up efforts around a more detailed International Crossbill Project as outlined below. More to come on that later.

DISCLAIMER

While much has been learned in recent years about Red Crossbills, there are still many enduring questions. As UC-Davis finch researcher and Finch Research Board member Tom Hahn often says, “never completely trust a crossbill.” Our understanding of how these populations interact and to what extent they are evolutionarily divergent and reproductively isolated is still not that well understood. Birds that give certain call types appear to preferentially mate with others that give their own call type, but the big question remains: is this what happens under all environmental conditions? To answer this question, we really need recordings of paired birds.

Some of the statements under “known range” below are still somewhat provisional and reflect only what has been documented to date – this is especially the case for Type 7 and Types 6 and 11 in Mexico and Central America. The basic ecology of Types 6 and 11 are marginally known, as is the extent of movements that they may or may not undertake. With relatively few recordings from Mexico, there is much complexity yet to be understood, including the very interesting possibility that an additional Type might exist in the hard to get to lowlands of the pine savannas areas of the Mosquitia (pers. comm. John van Dort) of Honduras.

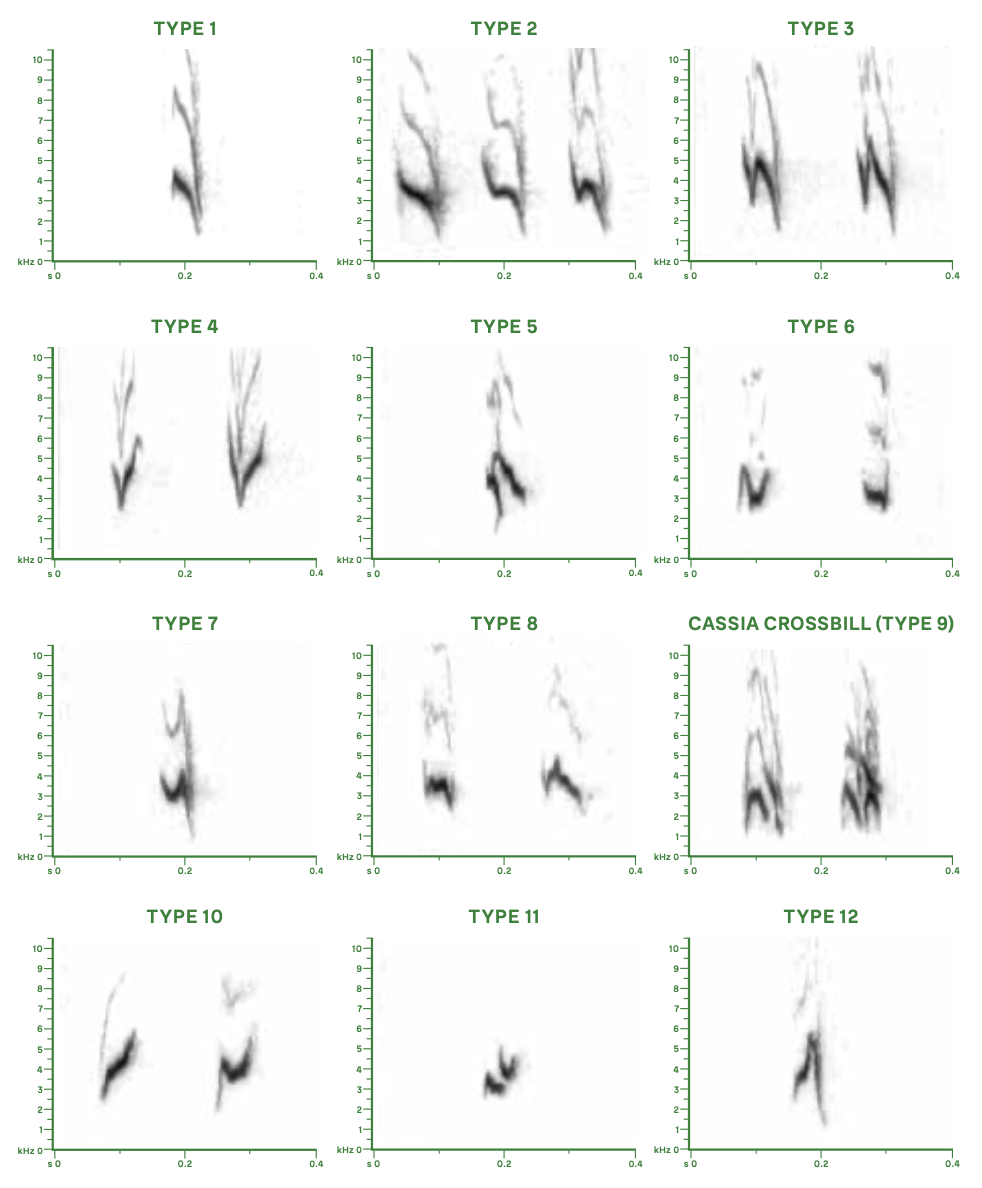

RED CROSSBILL CALL TYPES

It can be quite challenging to differentiate flight calls of the various Red Crossbill call types, but with some practice it’s not an impossible task. The flight calls are the sound typically described as jip-jip-jip and most frequently heard when the birds are flying overhead. In order to find and identify crossbills, it’s essential to develop a familiarity with their flight call vocalizations, which can also be occasionally given by perched birds. In each section below we will try to describe the differences between the flight calls of Crossbills of North America, including the various species, with a focus on differentiating the various call types. Flight calls are the most common vocalizations you will hear when encountering crossbills.

Type 1 – Appalachian Crossbill (Young et al. 2011)

— Medium-billed

Taxonomy: Subspecies has been referred to as L. c. pusilla (fits type 2), but has also been referred to as L. c. neogaea (best fit newly described type 12). If we’re trying to assign subspecies to call types, then this population needs a new name, as neither suggested classification fits its range and characteristics.

Known range: The core zone of occurrence (area where a type occurs most commonly) for Type 1 is the Appalachians from southern New York and the Berkshires of Massachusetts to northern Georgia and northeast Alabama (Young et al., 2011); occasional in Adirondack Mts., NY, and central Massachusetts northward into New England, s. Ontario, Maritimes, and perhaps Great Lakes; rare to very rare in West, but a bit more common in coastal areas, especially Alaska. Rare to uncommon most years along east coast south of Maine where type 12 is common. [eBird map]

Movements and Strategy: Less irruptive and is likely a more localized generalist rich patch exploiter that conifer switches on a more regional landscape level than types 2, 3 and 4. Mostly resident in East; rarely irrupts into Pacific Northwest. New records, mostly single birds, have been confirmed the last decade in Colorado, Arizona, Montana, Texas and Arkansas.

Trees Most Associated with: In the east: red and white spruce, eastern white pine, eastern hemlock, and hard-coned pines such as Virginia, pitch, and loblolly. In the west mainly uses Sitka spruce and western hemlock.

Flight call: A hard, quick, attenuated chewt-chewt similar to the chip of a Kentucky Warbler; compare to the softer Type 2.

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/300643321

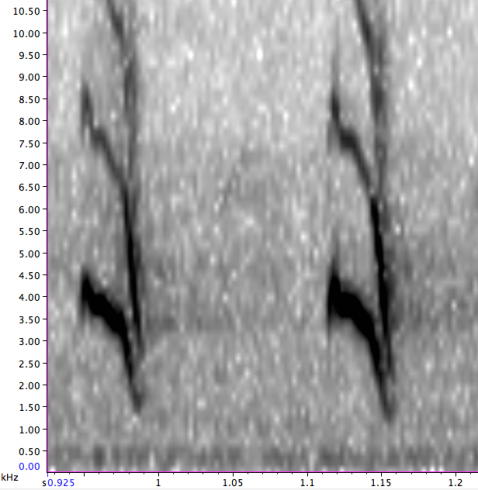

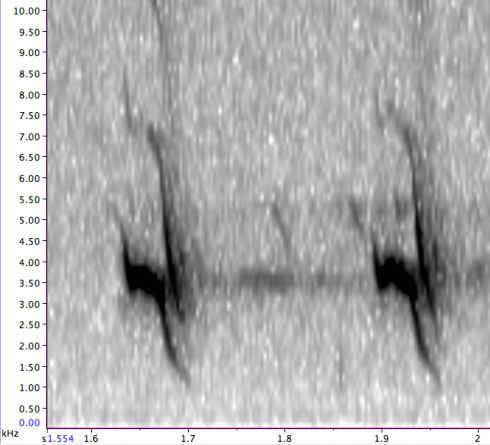

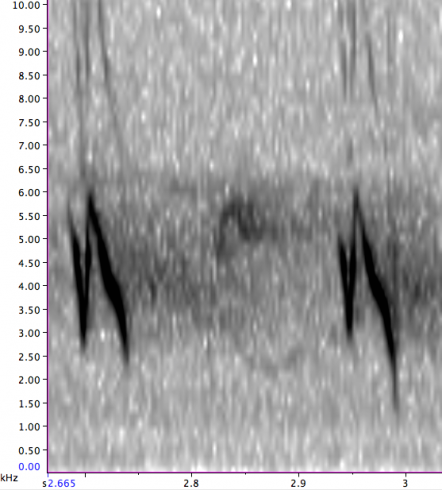

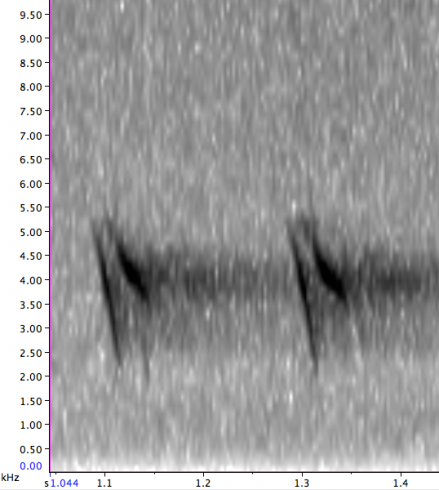

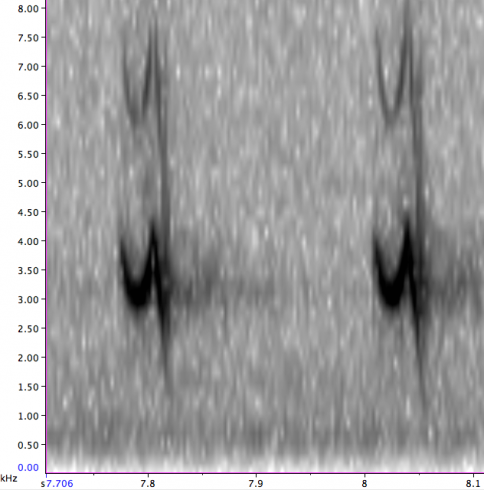

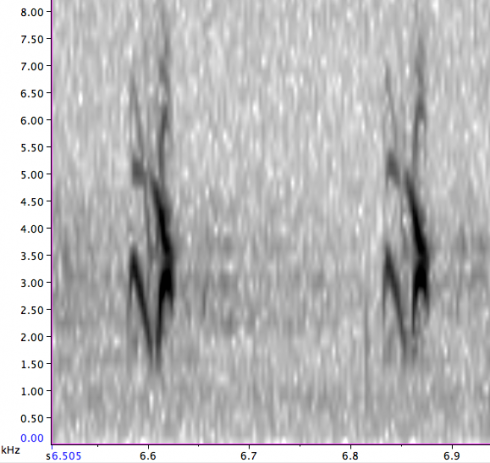

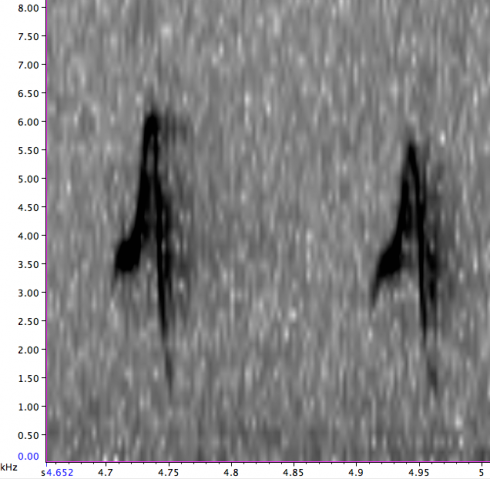

The Type 1 Red Crossbill flight call can sound like Type 2 Red Crossbill. In both call types the spectrograms are dominated by a downward component. To be able to identify these two types with certainty, audiospectrographic analysis is essential. On good recordings, a Type 1 spectrogram starts with a very short initial upward component the majority of time (it sometimes doesn’t appear at all, especially in poor recordings), and a downward part that descends more quickly than in Type 2 (duration of type 1 call is <.04s). Overall, the Type 1 flight call is a more attenuated, dryer and harder flight call than the Type 2 and it sounds like chewt-chewt-chewt. Type 1 calls often have especially strong harmonic elements (mirror images of the call at a higher pitch) in comparison to other types, and these elements may sometimes differ slightly from the main call, approaching polyphony (see Type 5 for a deeper discussion of polyphony). Sometimes Type 12 calls can be a bit more overslurred, and these recordings can approach the look and sound of type 1, especially if the two have been hanging out together. In these cases, like with type 10, a majority of the energy of the Type 12 flight call is usually given in the upward component.

Type 2 – Ponderosa Pine Crossbill (Benkman 2007)

— Large-billed

Taxonomy: Would be most appropriately assigned to subspecies L. c. benti, but, in part, has also been assigned to L. c. bendirei.

Known range: Core zone of occurrence is the Intermountain west of the Rockies, Cascades and Sierra regions. Often most common call type in the Interior West but can be found continentwide in U.S. to the eastern states and into very n. Mexico and parts of s. Canada. [eBird map]

Movements and Strategy: Likely a nomadic rich patch exploiter that conifer switches on a large continent-wide scale. Highly irruptive and can occur nearly anywhere even into the Plains states, which appears to happen with regularity. “Kinked” Type 2s are somewhat regular visitors to the western Great Lakes, and can irrupt into the Northeast in large numbers, as they did in 2023. Also irruptive onto the Pacific Northwest Coast, where there was a significant movement in the fall of 2020. One of the biggest irruptions of this type occurred in the Great Lakes and Northeast in 2023-2024.

Trees most associated with: In the west, proposed key conifer is Ponderosa pine, but readily feeds on Douglas-fir, spruces and other hard-coned pines such as lodgepole and Jeffrey pines in the west. During breeding it has been known to associate with upwards of 18 different species of conifers and would therefore be better named the Eclectic Crossbill or even American Crossbill. Type 2 uses white, red, jack, pitch, Virginia and table-mountain pines, and red and white spruce in the east.

Flight call: Like Type 1, but a husky, deeper and lower choowp-choowp or chew-chew; can recall Pygmy Nuthatch or Olive-sided Flycatcher’s pip-pip-pip. Western birds are a bit more “ringing” or even occasionally squeaky in quality, as compared to eastern birds. Compare squeaky sounding birds to Type 3.

Type2_flight_call_kinked_ML 44960

Type2_flight_call_unkinked_ML 1612991

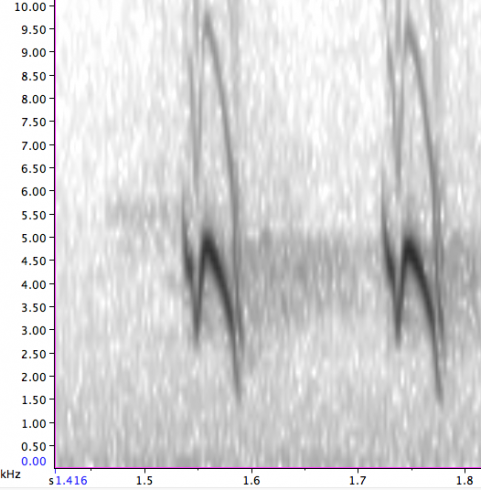

Type 2 flight calls are a bit lower and more husky sounding than those of Type 1. The downward component of the spectrograms is more gradual and modulated (duration of call is >.04s), and the initial upward component found in Type 1 is absent (unkinked spectrogram made from Macaulay Library #161299). Additionally, the call (as it appears on the spectrogram) will often level out a bit before continuing its downward trend. The call sounds like a choowp-choowp-choowp or chew-chew-chew. Both types can have secondary ending components, but they’re stronger and much more often present in Type 1. Additionally, the entire Type 2 flight call is typically given below 4.5kHz whereas the highest point of the initial upward component of the Type 1 flight call is usually between 4.5-5 kHz. This type tends to produce an “unkinked” spectrogram in the east (see unkinked Red Crossbill Type 2 Call). In the west, the Type 2 will often produce what is called a “kinked” spectrogram (see kinked variant above), and birds producing this type of spectrogram seem to be rare in the east outside of years kinked Type 2 irrupts eastward. This kinked call type first goes down and then back up before going back down. When type 2 and 3 rarely come in contact be on the lookout for rare occasions where kinked Type 2 and 3 can start to look and sound like each other, but their (Type 2) frequency range is still a bit lower and narrower consistent with kinked type 2. Typically they still sound a bit stronger and huskier. To the ear, Pieplow (2007) likens some Type 2 calls to the piping calls of Pygmy Nuthatch or the pip-pip-pip call of Olive-sided Flycatcher.

Type 2 has a fairly distinctive ‘toop’ or excitement call, sounding somewhat agitated and often given in series. It can be coarsely described as a flat ‘toop’ sound, vaguely similar to some sparrow or Winter Wren chips but delivered with a lower pitch. This sound is most often heard in the presence of a predator such as a Northern Pygmy-Owl, or in nesting situations.

Toop/Excitement call: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/615821364

Type 3 – Western Hemlock Crossbill (Benkman 2007)

— Small-billed

Taxonomy: The “Little Crossbill” best matches L. c. minor, but that name has also been applied to small-billed Type 10.

Known range: Its core zone of occurrence is in the Pacific Northwest where it primarily likes to feed on smaller soft-coned conifers such as Western Hemlock; and can be found in numbers in the Great Lakes, northeast, Ontario and Maritimes during irruptions. [eBird map]

Movements and Strategy: Likely a nomadic rich patch exploiter that conifer switches on a continent-wide scale similar to types 2 and 4. Highly irruptive into the Great Lakes, Northeast, Ontario and likely Maritimes every 3-10 years – last large irruption occurred 2017-18 (before that 2012-13), which was one of the largest and earliest starting irruptions for this type on record.

Trees most associated with: Proposed key conifer is western hemlock but readily feeds on small and soft coned conifers such mountain hemlock, Engelmann, Douglas-fir, and Sitka and blue spruce in the west; in the east, most often uses eastern hemlock and white and red spruces. Occasionally resorts to hard-coned pines in periods of winter food scarcity (Centanni et al., 2024).

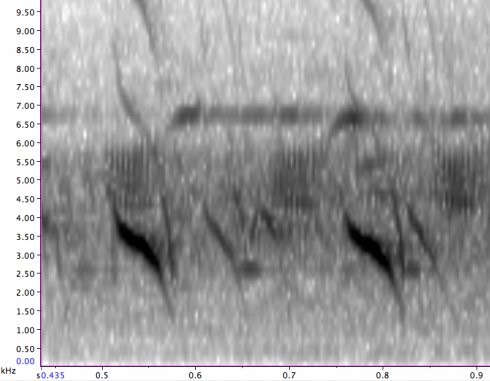

Flight call: A squeaky or scratchy tik-tik or kyip-kyip; highly distinctive.

Type3_flight_call_ML 136592 (now in ML as ML71525571, despite file names here)

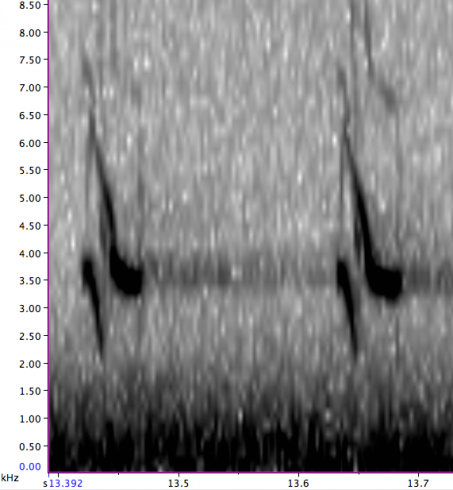

The flight call of the Type 3 is squeakier and more scratchy sounding than those of the other types. Type 3 tends to produce two slightly different spectrograms– one looks a bit like a lightning bolt with its zig-zag appearance – it starts out with a downward component followed by a short upward component connected to a second downward component. The other looks a bit like the letter “n”. Occasionally, there can be tails at both the beginning (less common) and end of the typical zig-zag appearance. Additionally, during the second downward modulated component, the tik-tik-tik or kyip-kyip-kyip call can level out just a bit as it continues downward. Type 3 can sound a bit like a scratchier or squeakier version of a Type 1 or 2, but Type 1 are sharper and Type 2 huskier and deeper sounding. When type 3 and 2 rarely come in contact be on the lookout for rare occasions where kinked Type 2 can start to look and sound like type 3, but their frequency range is still a bit lower and narrower like a kinked type 2. Additionally, if the scale is too small, the spectrograms of Type 3 can even be confused with types 5 as well — this is one of many reasons why we advocate for a universal scale to be used for analysis and one for publications. This type of standardization will become part of an International Red Crossbill Project that FiRN will be launching.

Type 4 — Douglas-fir Crossbill (Benkman 2007)

— Medium-billed

Taxonomy: Unclear but possibly L. c. vividior.

Known range: Core area is the northern Pacific Northwest and Northern Rocky Mountains, with birds occasionally found farther south in the Intermontane West; Local in the Western Great Lakes during irruptions and a bit more rare in the Northeast. [eBird map].

Movements and Strategy: Likely a nomadic rich patch exploiter and conifer switcher on a large landscape level similar to types 2 and 3. Occasionally irrupts to Intermontane West and Great Lakes and less commonly to the Northeast. Type 4 embarked on their largest Northeast irruption in known history in late summer to fall 2023, reaching the Great Lakes, Adirondacks, and New England in large numbers. First state records have already been established in 2017 for Minnesota and Wisconsin and a range extension has also been documented in the Sierra Nevada mountains of California. Type 4 actually bred in numbers, utilizing primarily Eastern White Pine in Quebec, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Vermont and Maine during the 2024 irruption. Other eastern records of Type 4 include a few recordings from Ohio in the 1969-70 (see Borror Laboratory of Bioacoustics’ collection) invasion and a couple from Michigan (Groth 1993).

Trees Most Associated with; Proposed key conifer is coastal variety of Douglas-fir, but will use interior variety of Douglas-fir with some regularity; also uses various spruces including Engelmann, white and blue; and white pines, including when it moves eastward. Nested utilizing jack and red Pines in Wisconsin 2018 and eastern white pine New York, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts and Maine in 2024. Was associated with bumper Ponderosa pine (with a couple juveniles) in Oregon early November 2024. Will also occasionally use hard-coned pines such as Ponderosa and lodgepole in periods of late winter food scarcity (Centanni et al., 2024).

Flight call: A bouncy plick-plick-plick or pwit-pwit-pwit; very distinctive, but compare to Type 10 and 6.

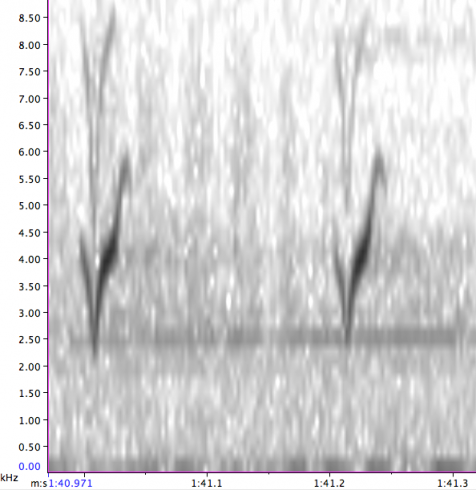

The flight call of the Type 4 is one the easiest to recognize even when compared to Type 10 (it was split from Type 10 in 2011; see Type 10 below) and is a very bouncy, almost musical down up plick-plick-plick. The spectrogram (Red Crossbill Type 4 Call) is dominated by a down-up component with the ending section looking very similar to the Type 10 flight call. Sometimes the spec can appear to look like a checkmark as it does in the second spectrogram above. Thin sounding type 4s can be hard to identify from Type 10. Faint sonograms may lose the initial downward element altogether, but the upward element is typically steeper and with a broader frequency range than Type 10. Type 6 can also lead to some confusion in both sound and spectrogram, but Type 4 always has a deeper “V”-shape in on the spectrogram, generally bottoming out around 2 kHz. Type 4’s flatter sound and the lower pitch on average separate it from Type 6’s obvious ringing sound.

Type 4 has a distinctive toop call, often given when predators are nearby or during the breeding seasons. Type 4 toops sound fairly weak and somewhat thin and can be described as “plink plink”. The sound is fairly low-pitched, and difficult to confuse with other birds with which it overlaps in habitat. They look like half of an infinity sign.

Type 4 Toop calls: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/615312708

Type 5 – Lodgepole Pine Crossbill (Benkman 2007)

— Large-billed

Taxonomy: Would be most appropriately assigned to subspecies L. c. bendirei, but L. c. benti has also been assigned to birds that may represent Type 5.

Known range: Core Zone of occurrence in west is where Rocky Mountain lodgepole pine and Engelmann spruce are most common. Western in U.S. and Canada; vagrant to the Great Lakes and Northeast. [eBird map]

Movements and Strategy: More localized and regional and likely utilizes more of a key conifer type strategy than most of the other call types. It does appear to conifer switch some as well between lodgepole pine, Douglas-fir, Engelmann spruce, blue spruce and even occasionally Ponderosa pine. Can irrupt in small numbers in parts of the Intermontane West, but is vagrant in the east to Massachusetts, New York and Maine.

Because of stable cone crops, Type 5 can be resident throughout much of the west where Rocky Mountain Lodgepole Pine is common. A very small population seems to reside on the high-elevation crest of the Cascades in Oregon and Washington, but its foraging preferences are not well known. Very rare wanderings into the Pacific coastal ranges also occur.

Trees Most Associated with: Proposed key conifers are lodgepole pine and perhaps Engelmann spruce. Readily uses blue spruce and less often uses ponderosa pine, Douglas-fir, and white pines.

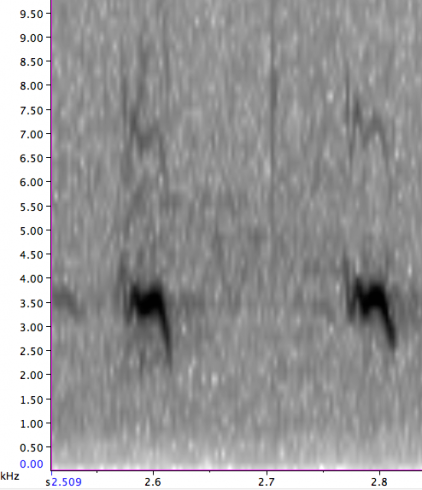

Flight call: A springy or twangy clip-clip-clip or chit-chit-chit; quite distinctive and level sounding.

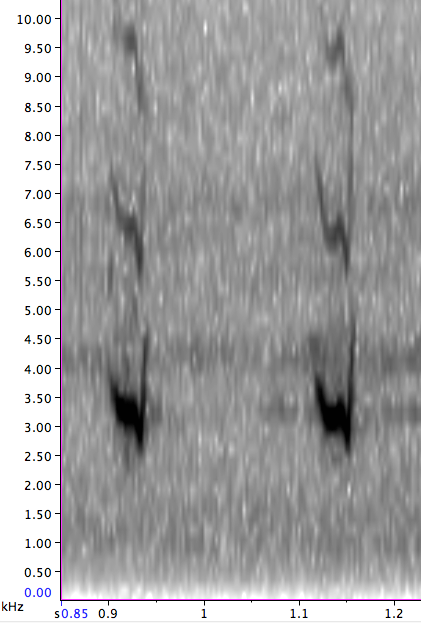

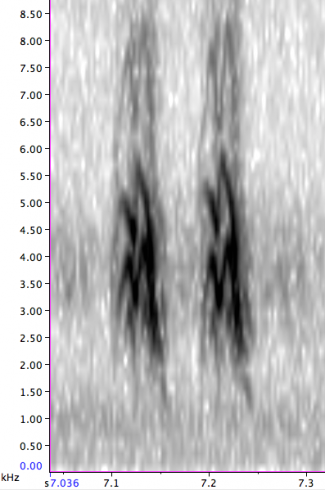

Type 5 Red Crossbills have two elements that drop in frequency, but the two elements are given in very slightly different frequency domains. The lower elements are generally simpler and show less variation individually, whereas the upper elements usually rise sharply before modulating downward (Groth 1993). The second element often starts a fraction of a second after the first element. On the spectrogram this second element sometimes hints at connecting to the first element. Generally speaking, both elements are given nearly simultaneously. That both elements modulate differently, basically over the same time span, is likely evidence that the Type 5 uses different halves of its syrinx, thus producing sound polyphonically not unlike a Catharus thrush (Groth 1993, Pipelow 2007), a phenomenon which occurs across several call types, but most consistently and conspicuously in this type. Unlike other types, the orientation of the call in general is slightly from the top-left to bottom-right as it would read directionally on a piece of paper. To the human ear, Type 5 can sound like very twangy clip-clip-clip and therefore unlike other types except Type 3 (which sounds softer and scratchy). However, it should be noted that many types mimic the flight calls of other types in their songs, and Type 5 is the most commonly mimicked type in the west, so care should be taken to ensure the calls are delivered independently and not alongside other song elements.

Type 6 – Sierra Madre Crossbill (Benkman 2007)

— Large-billed

Taxonomy: Likely equates to L. c. stricklandi

Known range: Its core zone of occurrence is the Sierra Madre Occidental (Benkman 2007). Southwest U.S. to southern Mexico and Honduras; possibly also Guatemala and El Salvador (recordings needed); in the U.S. it occurs in se. Arizona and sw. New Mexico; museum specimens have been noted from Colorado and California. [eBird map]

Type 6 has been documented in southeastern Arizona’s Chiricahua, Huachuca, Pinaleño and Santa Catalina Mountains and the Pinos Altos mountains in southwestern New Mexico. Recordings also document this type into southern Mexico and further south to Honduras; Type 6 and Type 11 occur sympatrically in the highlands from Chiapas to Honduras. There is one record northward to California (San Diego Natural History Museum SDNHM 873; pers. comm. Lance Benner and Walter Szelinga) and Colorado has six specimens that match L. c. stricklandi (e.g., DMNS 4294, 4296, etc.; Spencer 2009)

Movements and Strategy Unknown; some years perhaps more common in Arizona than others? More data needed!

Trees Most Associated With: Several hard-coned pine species of Mexico, especially Apache pine.

Flight call: A cheep-cheep, ringing, and tonal. Compare with type 4.

Type 6 flight call aF743 (The Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at Berkeley)

The cheep-cheep-cheep flight calls of Type 6 are tonal and slightly ringing with a downward-modulated frequency and an abrupt terminal rising component (Groth 1993). Type 6 can be confused with Type 4 in some instances, however Type 4’s flatter plick-plick-plick sound separates it from Type 6’s slightly ringing cheep-cheep-cheep sound. Spectrally, Type 4 always has a deeper “V”-shape in frequency, generally bottoming out around 2 kHz. The gentler, “v”-shapes of Type 6 bottom at 2.5-3 kHz. Not much is known about Type 6, but by ear it does sound similar to the large-billed Type 8 of Newfoundland, although the spectrograms are obviously different. Type 6 is much less modulated than the m-shaped Newfoundland Type 8.

Type 6 has a diagnostic toop call, most often given in the presence of a predator such as a Northern Pygmy-Owl. Type 6 toops sound quite similar to flight calls of Western Bluebirds, albeit with a more polyphonic character and a somewhat sharper sound. It can be loosely described as “schip schip”.

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/45011851

Type 7 – Enigmatic Crossbill

— Medium to large-billed (Young 2012)

Taxonomy: Subspecies unknown as this remains an “enigmatic” call type.

Known range: Core zone of occurrence is likely eastern British Columbia, western Alberta north to southern Yukon territory. Occasional south to northern Colorado and California. This is among the rarest crossbill types in North America, with only a few handfuls of diagnostic recordings.

Movements and Strategy: Perhaps similar to Cassia and Type 5, but with a more northerly distribution. Unknown whether more of a key conifer type or more of conifer switcher type. More study needed.

Trees Most Associated With: Unknown, but likely lodgepole pine north of the range of Type 5 and Cassia. Very well could be a bit more of a generalist that uses lodgepole pine and Engelmann, white and “hybrid spruce” where the two species overlap.

Flight call: Husky jit-jit-jit somewhat intermediate in sound between Type 2, 5 and Cassia. Some rare Type 12 can sound similar as well. Type 7 is the flight call type that needs the most recordings (and measurements of the same audio-recorded individuals) in order to pin down flight call variability and geographic distribution.

Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, Berkeley Type 7_flight_call_aF497

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/590216701 (Tom Johnson ML recording)

The spectrogram of Type 7 is sometimes shaped like a small letter “u”, and if recording is edited too much (e.g. cleaned up too much[CTC2] …..too much is removed) it can look polyphonic like Type 5 and Cassia. It is also pretty low pitched and happens in a narrow frequency range between 2.5-4.5kHz. The main frequency of sound (jit-jit-jit) can be described as sometimes having a short initial fall. More recordings are needed.

Type 8 – Newfoundland Crossbill (Griscom 1937)

— Large-billed

Taxonomy: The name L. c. percna is usually associated with this type and the subspecies percna is still listed as Threatened by the Canadian Wildlife Service. It was fairly recently down-listed to threatened (http://www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/species/speciesDetails_e.cfm?sid=814)

Note that some authorities (including eBird/Clements!) use the name L. c. pusilla as a synonym of L. c. percna.

Known range: Core zone of occurrence is the mainly restricted to the island of Newfoundland, but also now confirmed from Anticosti Island, Quebec (http://www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/species/speciesDetails_e.cfm?sid=814).

Movements and Strategy: Thought to be resident to island of Newfoundland, but at least rarely moves to Anticosti Island (see above report), Quebec; perhaps moves to Magdalen Islands, Quebec, or other nearby Maritime coasts as well.

Trees Most Associated With: Type 8 has been proposed to be most closely associated with black spruce found on Newfoundland (Benkman 1993b), but it appears to also feed regularly on white spruce, eastern white, and red pine and can be commonly found at feeders from February-May while breeding (Young et al. 2012).

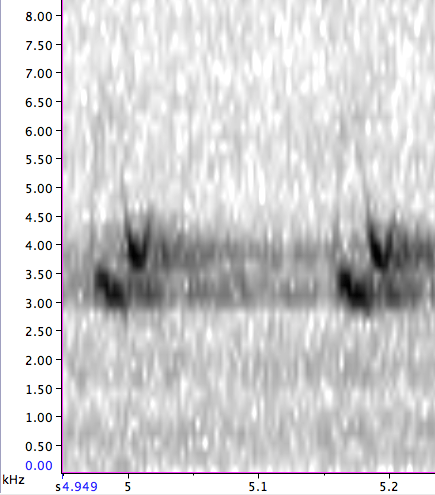

Flight call: Cheet-cheet, ringing and complexly modulated.

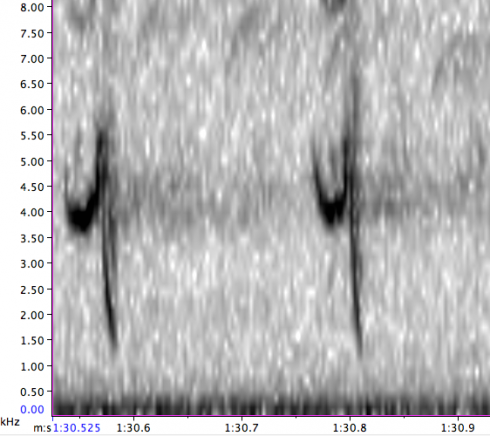

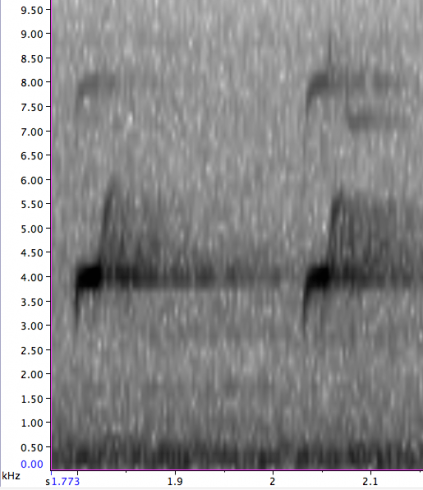

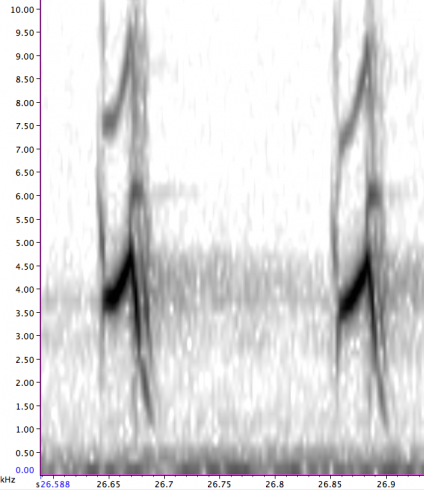

The sound of the original recordings can be described as flat, quick, and a bit harsh compared to the ringing quality of the more recent Newfoundland recordings. The more recent Newfoundland recordings depict a complexly modulated call that vaguely resembles the letter “M” (Young et al 2012).

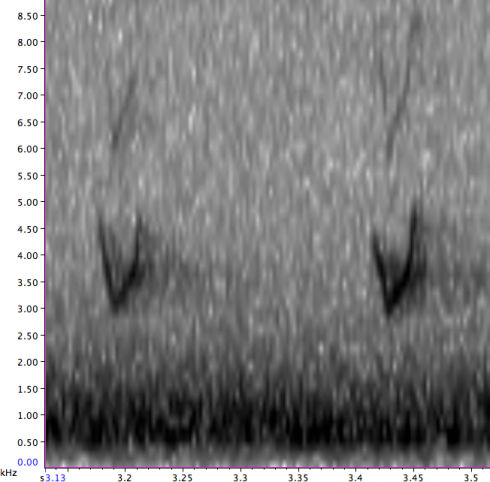

The main frequency of sound is in the 3.25 to 4.0 kHz range. The flight call can be described as up-down-up-down cheet-cheet-cheet. Additionally, there are often very subtle modulated components attached on either end. Like Type 6, the sound of the flight call of these more recent Newfoundland recordings can be described as bell-like or ringing and clear, resembling the cheep call of the Evening Grosbeak. Type 8 flight calls are much more modulated than Type 6 though.

Additional Note:

Audiospectrographic analysis of recordings during 2005-2011 (n=30; 2 hr 37min of recordings) confirms the presence of a unique Red Crossbill type on the island of Newfoundland (presumably subspecies percna; see taxonomy below). These recordings were audiosprectrographically compared to the original two 4-second recordings used by Groth (1993), and much to our surprise, they did not match (Young et al. 2012). The most parsimonious explanation of the differences between the 1981 recordings and the 2005-2011 recordings, then, is that the more recent and complete set of recordings is typical of Type 8 Red Crossbill. Thus we deduce that the more recent recordings refer most reliably to Type 8 (Young et al. 2012). A study by Doug Hynes and Edward Miller further corroborated this finding (Hynes and Miller 2014).

Cassia Crossbill (Benkman et al. 2009)

— Large-billed (formerly Type 9)

Taxonomy: Loxia sinesciurus. Formerly known as “South Hills Crossbill” or “Type 9”. Was elevated in 2017 to species status as Cassia Crossbill Loxia sinesciurus and is already listed a major conservation concern: http://www.hcn.org/articles/endangered-species-will-the-wests-newest-species-go-extinct

Known range: Core Zone of Occurrence largely restricted to South Hills and Albion Mountains of southern Idaho, in Twin Falls and Cassia Counties only [eBird map], but there are now several records from Colorado, Wyoming, and California.

Movements and Strategy: Uses more of a key conifer type strategy as it has been mostly resident until last ~ 5 years. [CTC3] [MY4]

Trees Most Associated with: Uses local variety of lodgepole pine that has evolved in absence of cone-predating pine squirrels. Has used other pines in Colorado and California and also spruces in Colorado.

Flight call: Very dry dip-dip-dip or dyip-dyip-dyip; very distinctive.

Cassia Crossbill_flight_call_65163941

Cassia Crossbill_flight_call_64374391

The Cassia Crossbill spectrogram starts with an initial upward component, therefore looking a bit like the Type 1 spectrogram. The downward modulation of the flight call is consistently given in a lower frequency domain (below 4.0 kHz) than Types 1 and 2. Cassia Crossbills are one of a few types that often produce sound polyphonically (see Type 5 for discussion on polyphony) and also has secondary ending components. Overall, the Cassia Crossbill flight call sounds much lower and have a flat, harsh quality. To our ear the dip-dip-dip call actually has an agitated quality to it. It sounds a bit like Type 11.

Additional Note: This type was initially described as a full species–the South Hills Crossbill (Loxia sinesciurus)–by Benkman et al. in 2009 (Benkman et al. 2009). Starting in 1996, Benkman began studying this resident call type of Red Crossbills in the South Hills and Albion Mountains of southern Idaho. Cassia Crossbill is adapted to feed on Lodgepole Pine (var. latifolia) in an area that lacks tree squirrels (e.g., Red Squirrel Tamiasciurus hudsonicus), a primary cone predator, and the crossbills thus are the primary predators on pinecones in those mountains. In the absence of mammalian cone predators in this area, the South Hills Crossbill has been tightly coevolving with this specific variety of Lodgepole Pine, driving the South Hills Crossbills to have larger bills to access seeds in better and better protected cones. This type was originally thought not to wander much at all, except perhaps rarely to adjacent mountain ranges to the north (Benkman et al. 2009). However, recent wanderings to coastal California, and Colorado where birds have bred, suggest that irruptive behavior may occur, perhaps in response to the Badger fire that ravaged as much as 50% their home range. AOU did not accept the original proposal to split this form in 2009 on the basis of the lack specimens and genetic work. Since then, a genetic study has been done on the entire complex except Type 8 (Parchman et al. 2016) and specimens were deposited in the Museum of Vertebrates, University of Wyoming. Type 9 was then recognized as a species in 2017 (Cassia Crossbill) based on it being genetically distinct from the remaining call types, having different flight call vocalizations, and the fact that it breeds mainly in April-July and starts molting in July before completing molt in September (Benkman et al. 2009, Parchman et al. 2016); the other call types often go through a partial molt in fall and breed late summer and early winter. In 2021 Geoffrey Hill proposed the species be lumped back into the Red Crossbill complex again, and vote went from 8-2 to 6-4 in maintaining it as a species. This proposal was written before the recent wandering was known. Stokes Guide to United States and Canada treated the population as Cassia Crossbill but also as part of the “Red Crossbill Complex” in case status changes.

Type 10 – Sitka Spruce Crossbill (Irwin 2010)

– Small to medium-billed

Taxonomy: Best matches L. c. sitkensis, but specimens identified as this form probably include other types of similar morphology such as Types 1, 3 or 4.

Known range: Core zone of occurrence primarily the narrow fog belt less than 10 miles from the Pacific Coast from Vancouver Island, British Columbia to Central California, but occasional irrupts into the east in movements which are not yet well understood. There are a few records north to the Kenai Peninsula of Alaska, and curiously a handful of records in far interior northern Canada.

Movement and strategy: More of a key conifer type strategy and often one of the more non-migratory types, with birds very rare even 5-10 miles inland from the coast in the Pacific Northwest. However, birds matching this type have been recorded occasionally in the East for some time, and their origin warrants further investigation.

Trees Most Closely Associated with: Displays a consistent and obligatory preference for Sitka spruce in the Pacific Northwest (Centanni et al., 2024) but rarely has been seen feeding in Douglas-fir, western hemlock, and the “shore” subspecies of lodgepole pine. Uses spruces and pines in rare eastward irruptions and was confirmed nesting in late winter/spring in jack and red pine barrens in Wisconsin during the 2017-2018 irruption.

Flight call: Very dry thin whit-whit; recalls Empidonax flycatcher whit note; very distinctive. Compare with Types 4 and 12.

Type 10_flight_call_ML68288161

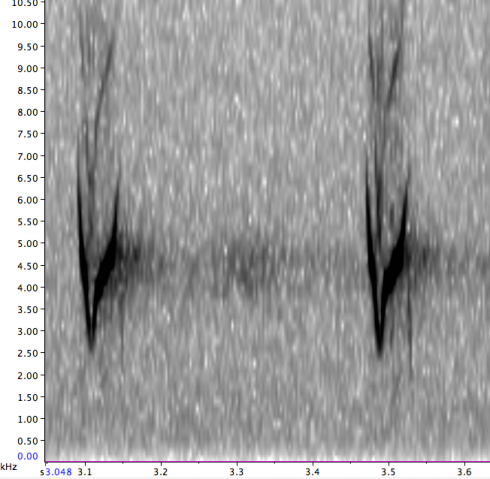

The idea that there was a crossbill call type that gave a flight call similar to Type 4 but lacked a strong downward component had been known for several years, but Ken Irwin was the first to describe it formally and clarify its apparent ecological relationships (Irwin 2010). The flight call of Type 10 is perhaps one of the easiest call types to recognize except for when it rarely comes in contact with Type 4, when it can rarely have a very shallow initial downward component. It’s a very thin, slightly weak whit–whit–whit. The whit-whit-whit sounds much like the whit call of some Empidonax flycatchers (e.g., Least, Dusky, Gray, Willow, or Buff-breasted Flycatcher). The spectrogram is dominated by an upward component. There are distinct differences between Type 4 and 10 spectrograms, with Type 4 containing a downward and upward component and Type 10’s usually just giving the upward component (but see Type 4 for discussion of faint sonograms). Type 4 calls usually begin much lower that Type 10s as well, which rarely dip below 3 kHz. In type 12s (previously lumped into type 10), a consistent ultimate downward element is clearly distinct from the pure upward sonogram and tone of Type 10. Type 10 spectrograms do appear to be more variable than most of the other types (Irwin 2010), however, and some were uneasy about the level of variation before northeastern Type 12 was split from this type in 2024.

Additional Note: It should also be noted that Benkman (1993a) predicted a Sitka Spruce associating crossbill type many years ago, but that was at first thought to be Type 1.

Type 11 – Central American Crossbill (Young and Spahr 2017) — Large-billed

Taxonomy: Matches L. c. mesamericana

Known range: Core zone of occurrence Guatemala, Honduras, Belize, Nicaragua, and El Salvador (recordings needed); [eBird map]

Movements and Strategy: Unknown

Trees Most Associated With: Hard-coned pine species of Central America, most specifically Mexican yellow pine Pinus oocarpa (pers. comm. John van Dort)

Flight call: Type 11 birds give a flat, polyphonic flight call that can sound similar to the Cassia Crossbill or some lower-frequency variants of Type 5. It could be represented by drip-drip-drip, and sounds very different than the slightly ringing quality heard in the Type 6 birds with which it shares habitat.

Additional Note: Type 11 seems fairly common in high-elevation conifers, particularly Pinus oocarpa, in Central America into southern Mexico. However, relatively little is known about its movements and limits of distribution. Thus far John van Dort has been instrumental in obtaining several recordings of this type in the field, but more study, and more recordings and measurements (preferably of the same birds) are still needed!

Type 12 – Northeastern Crossbill (Young et al. 2024) – Small-billed to medium-billed

Taxonomy: Split from Type 10 in 2024 based on marked differences in flight calls and migratory/ecological behavior. We suggest that L. c. neogaea should be resurrected as the subspecies for the Type 12 red crossbill. A likely type specimen exists, taken February 9, 1886 in Lake Umbagog Maine, it is unclear whether a combination of morphometrics and genetics would be able to confidently verify that specimen as a Type 12 bird or not, given our current understanding that it is challenging to identify types on simple measurements alone (Griscom, 1937; Groth, 1993). L. c. neogaea is likely the “old Northeastern crossbill”.

Known range: Core range of occurrence is the northeastern cordillera of North America, with occurrence common in the Adirondacks, New England and Maritime coastal zone. Fairly common but in lower numbers across the Great Lakes and rare south along the coast to Maryland and rarely North Carolina. Very rare in the west, but records for Idaho, Oregon, British Columbia, Alberta, Alaska, and California have been documented since 2017.

Movements and Strategy: Likely a generalist rich patch exploiter as it appears to regularly conifer switch on a more localized regional landscape level than types 2, 3 and 4. Small scale irruptions within the east are often every other year or so, with flocks typically making coastal movements to pursue the best cone crops. In some years, birds move further afield south along the Atlantic Coast, and rarely to Appalachians where it overlaps with the much more mountain Interior (Appalachians) Type 1.

Trees Most Closely Associated with: Generally associated with Red Spruce and sometimes White Spruce in the northeast at the beginning of the cone cycle year in July-August. Also uses many pines, especially eastern white pine, red pine, pitch pine, and jack pine. Will frequently use planted Norway spruces in big crops years as well.

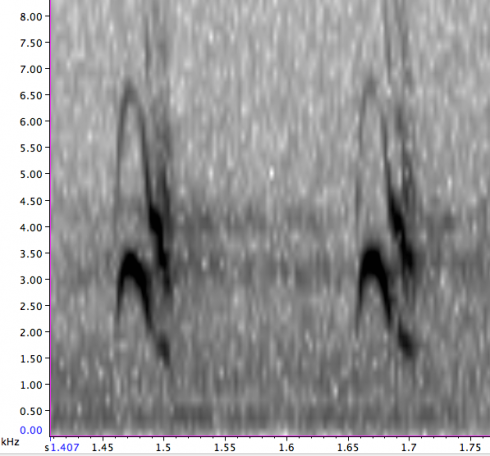

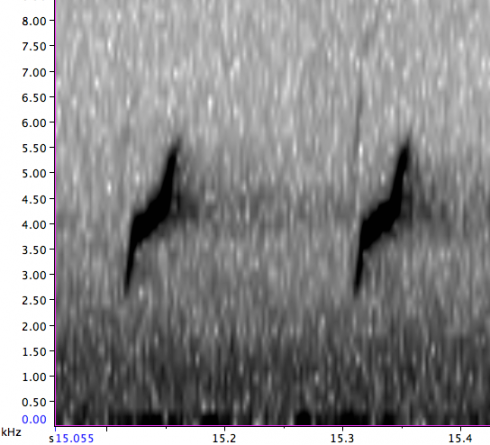

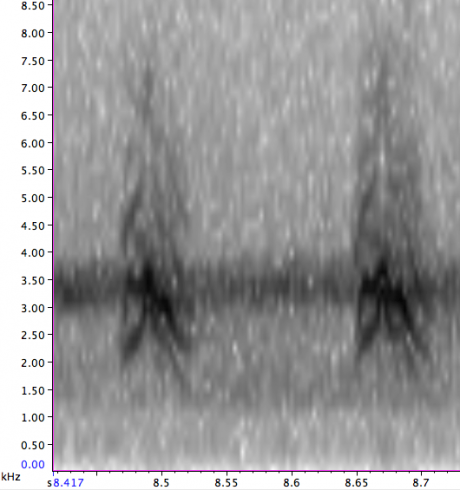

Flight call: Overslurred Type 12 (formerly over- slurred / western Type 10) gives a harder, squeakier kip-kip with a strong downward inflection at the end, looking like an upside down V.

Flight call begins with a moderately long rising element followed by a very steep decline, perhaps the most vertical drop of any crossbill flight call. Due to the long initial upward element, which is quite similar to Type 10 flight calls, this type was originally lumped with that species. Sometimes calls can be a bit more overslurred, and these recordings can approach type 1. The steep decline gives it both a distinctive appearance on sonograms and a fairly different tone from Type 10, however, like with type 10, the majority of the energy of the call is given in the upward component. When identifying Type 12 from Type 1 and eastern (“unkinked”) Type 2, consider Type 2s generally have a much shallower slope and typically no sign of an initial upsweep and Type 1s may have a small initial uptick or hook at beginning, but the upsweep is long, steep and noticeable on most all Type 12[MY5] . In good recordings, Type 1 is also typically heavily harmonic or occasionally polyphonic[CTC6] with secondary elements whereas Type 2 and 10 rarely have these elements.

Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, Berkeley Type 12_flight call_jM498

White-winged Crossbill (Gmelin 1789)

Taxonomy: Loxia leucoptera leucoptera. Unlike Red Crossbill, there’s no “call type” differentiation in the White-winged Crossbill in North America. Subspecies bifasciata is found across Eurasia, and, with further study, could be split to a full species given its notable differences in calls and ecological associations.

Known range: Core Zone of Occurrence is the boreal forest of Canada with occasional nesting in the northeastern states, Cascades to central Oregon, central Rockies to northern New Mexico, and along coastal areas of western Canada; in irruption years will move south into Plains and Appalachians. [eBird map].

Movements and Strategy: Highly irruptive, and even moves in large numbers into the Northeast, Rockies, Pacific Northwest every 5-15 years; Rare in the Plains. As with most other crossbills, especially the highly nomadic Types 2, 3 and 4, the species has three main movements a year: one in May-June when it searches for newly developed cone crops; another in October after breeding and molting; and sometimes a third in December-January looking for the last remaining good cone crops. In a very unusual irruption, large numbers of this species irrupted into the Pacific Northwest Sitka Spruce coastal zone south to Northern California in 2017-2018. The winter of 2021-2022 saw a record-breaking irruption throughout the west, with several flocks of hundreds documented in eBird.

Trees Most Closely Associated with: white spruce, black spruce and tamarack across the closed boreal forest of Canada; additionally uses red spruce in the northeastern states and southern Maritimes, Engelmann spruce in Rockies, and rarely Sitka spruce along the Pacific Coast. Readily uses “hybrid spruce (Engelmann x white) in British Columbia as well. Used Douglas-fir in British Columbia for nesting in late winter and early Spring of 2019. Will use a variety of conifers during irruptions south of normal breeding range too.

Flight call: The main flight call given by the White-winged Crossbill is a chattering very redpoll-like chyet–chyet or chet–chet call, usually doubled or tripled, and repeated once every second or two. This White-winged Crossbill flight call is a louder, twangier and more musical version of a redpoll flight note. Audiospectrographic analysis of the White-winged Crossbill is of somewhat less importance as long as you get the basic gist of their calls down. With some practice, this standard flight call of the White-winged Crossbill can be easily distinguished from any Red Crossbill vocal type or other finch species. White-winged Crossbills also give a second call that can be easily confused with the call of various Red Crossbill vocal types; however, it’s a sharper, quicker and thinner (veet–veet–veet) than any of the Red Crossbill vocal types. These veet–veet calls are more commonly given by perched birds, which may help separate from Red Crossbill flight calls. Please note White-winged Crossbills also give a rising whee call that is similar to some redpoll, siskin, or goldfinch flight calls. This rising call is never given by Red Crossbills.

White-winged Crossbill_103203_2

White-winged Crossbill_103203_3

Hispaniolan Crossbill (Banks et al. 2003)

Taxonomy: Loxia megaplaga. The Hispaniolan Crossbill was designated as a separate species from White-winged Crossbill in 2003 (Banks et al. 2003). The species has been isolated from White-winged Crossbills since the Pleistocene (Woods et al. 1992). The Hispaniolan Crossbill differs significantly from the White-winged Crossbill in vocalizations and in bill morphology. The bill of the Hispaniola Crossbill is 25% larger than that of the White-winged Crossbill, and is closer in size to the Red Crossbill (Loxia curvirostra; Benkman 1994, Parchman et al. 2007).

Known range: Core range of occurrence is Island of Hispaniola where it is endemic [eBird map].

Movements and Strategy: Non-migratory and resident to the island of Hispaniola.

Preferred trees: Primarily eats seeds of Hispaniolan pine (Pinus occidentalis)

Flight call: A dry or wooden chit–chit–chit

Status: Endangered and rare in high-elevation pine forests of Hispaniola. Available habitat is decreasing as a result of fire, logging, and conversion of land to agriculture.

CONCLUSION

Understanding how these differences relate to traditional taxonomy is fraught with complexity and is an area in need of additional research. One key component of any research on this complex is having plenty of recordings of the flight call types (optimally with measurements from the same recorded individuals). Due to their nomadic nature and tendency for overlap, labeling them to subspecies is likely not doable, except perhaps with ones where some level of isolation (whether by range or breeding) has been well documented like with the Newfoundland subspecies, ssp. percna (Type 8). A big part of the complexity is in nomenclature, since it is unclear how present types relate to named subspecies from the past. This is due in part to the fact that some of the named subspecies do not seem to be identifiable and multiple names may apply to a given population and/or type (i.e., some named subspecies are not valid). Additional complexity arises from the fact that we don’t understand the extent to which these different types are reproductively isolated and whether or not they are behaving as species according to the Biological Species Concept. Cassia Crossbill was split because it was found to be reproductively isolated — hybridization was found to be less than 1% (Benkman et al. 2009), whereas between Scottish, Parrot and Common Crossbill it was 5% (Summers et al. 2007). It could well be that some types represent distinct species, or it could be that they are better treated as distinct forms that have not yet evolved to represent distinct species. Thus, the study of various flight call types of Red Crossbills may inform us of our broader definition of what it means to be a separate species.

The 2025 eBird/Clements taxonomy (v2025) includes not only the nomenclature and taxonomy of species, but also of subspecies. Subspecies cannot be reported in eBird unless it is included as an identifiable group, but Red Crossbills can be reported to Type in eBird.

Every crossbill recording adds an important piece to the puzzle, especially when accompanied by notes on behavior and ecology, including tree species used for foraging and nesting. The conservation of crossbill call types will depend in large measure on our understanding of their complex distributions and ecological associations, and birders can make critical contributions to their conservation by recording crossbill calls and by reporting their findings.

Appendix A

Modifications Leading to Intermediates

Intermediate Type 4/10

Intermediate Type 10: Type 10 sounding and looking like Type 4, but we’re confident this is a Type 10: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/355006591[CTC7] [MY8]

Intermediate Type 10: Type 10 sounding and looking like Type 4, but we’re confident this is a Type 10: https://ebird.org/checklist/S40116539

Type 4 at 6s mark sounding a bit intermediate and like type 10:

https://ebird.org/checklist/S110884290

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/451610571

Intermediate Type 1 and 12

Intermediate sounding Type 1/12 Crossbills better left as Red Crossbill: https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/93949091

Intermediates

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/63102921

https://ebird.org/checklist/S73861209

Type 1 and 12 and they are trying to call match producing an intermediate:

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/415832021

Intermediate Type 2 and 3

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/83144091

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/80220861

https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/80219881

For more Crossbill sounds including toops and chittos, see Nathan Pieplow’s companion sounds to the Birds Songs of Eastern and Western North America:

APPENDIX B

Since an understanding of conifer species is essential to understanding crossbills, the above article discusses conifer species at some length.

Below is a list of the scientific names (with Wikipedia links) for the tree species mentioned in the article. For thorough accounts of the these birds’ complex relationships with different conifer species, please see our Crossbill’s Guide to Conifers for the east and west and/or the Stokes Guide to Finches.

PINACEAE

Pines — Genus Pinus

Pines can be broken down further into soft-coned pines (the two White Pine species listed below) and hard-coned pines (all the others listed below). At some points in the above article we refer to hard-coned or soft-coned species.

- Eastern White Pine Pinus strobus

- Western White Pine Pinus monticola

- Apache Pine Pinus engelmanni

- Jack Pine Pinus banksiana

- Jeffrey Pine Pinus jeffreyi

- Loblolly Pine Pinus taeda

- Lodgepole Pine Pinus contorta

- Pitch Pine Pinus rigida

- Ponderosa Pine Pinus ponderosa

- Red Pine Pinus resinosa

- Table Mountain Pine Pinus pungens

- Virginia Pine Pinus virginiana

- Mexican Yellow Pine Pinus oocarpa

- Hispaniolan Pine Pinus occidentalis

- Japanese Black Pine Pinus thunbergii

Douglas-firs — Genus Pseudotsuga

- Douglas-fir Pseudotsuga menziesii

Spruces — Genus Picea

- Black Spruce Picea mariana

- Blue Spruce Picea pungens

- Engelmann Spruce Picea engelmannii

- Norway Spruce Picea abies

- Red Spruce Picea rubens

- Sitka Spruce Picea sitchensis

- White Spruce Picea glauca

Hemlocks — Genus Tsuga

- Eastern Hemlock Tsuga canadensis

- Western Hemlock Tsuga heterophylla

- Mountain Hemlock Tsuga mertensiana

Larches — Genus Larix

- Western Larch Larix occidentalis

- Tamarack Larix Laricina

Additional Links

Below are links to several cuts containing multiple types. To hear a great comparison between Type 1 and Type 3 calls, try this link. In the first 10 seconds, the recording has a Type 1, followed by Type 3, and then Type 1 again, making for a particularly good chance to compare the calls side-by-side. To hear the differences between some of the toughest ones to differentiate, listen to this cut with Type 1, unkinked Type 2 and Kinked Type 2 (examples of “kinked” Type 2 are at 4s, “unkinked” Type 2 at 11s, and Type 1 at 14s.)

To hear a cut with similarly sounding Type 4 and 6 (and an “unkinked” Type 2 at 14s mark), listen here. The cut starts out with Type 4 and then Type 6 start to come in at the 3s and 5s marks, and are mixed in throughout the rest of the cut. The Type 6 is slightly higher in frequency, but has a narrower frequency range.

Lance Benner’s wonderful cut from Arizona has great examples of Types 2, 4 and 5, which to a trained crossbill ear, are fairly easily to differentiate in the field compared to the types in the above clips. Click here. At the 33s mark the flock takes flight and the majority of the birds are Type 5s initially, but at the 36s, 42s and 44s marks Type 2 can be seen and heard mixed in. At the 46s and 48s marks the first “V-shaped” Type 4 can be seen and heard, and then after the 1:06 mark until 1:19 it’s entirely Type 4.

To hear a long, and very interesting crossbill recording that includes a variety of songs and different crossbill flight calls, click here. In addition to the full gamut of crossbill sounds that one individual might produce (flight calls, toops, “social” songs, chitters, etc.), this amazing cut includes four different call types: Type 1, Type 2, Type 3, and Type 10. See if you can sort them out!

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Macaulay Library at The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, The Borror Laboratory of Bioacoustics, and The Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at Berkeley (aka Jeff Groth’s collection) for the use of recordings. A special thanks goes out to Craig Benkman, Jeff Groth, and Tom Hahn for getting us all started down the crossbill road – without their research, we would not be where we are today! I’d also like to thank Rodd Kelsey, Cody Porter, Lance Benner, Nathan Pieplow, Ken Irwin, Tayler Brooks, Andrew Spencer, Bob Dunlap, John van Dort, Anant Deshwal, Jamie Cornelius, Susan Kielb, Nick Anich, Ryan Brady, Junior Tremblay, Doug Hynes, Christophe Buidin, Yann Rochepault, Olivier Barden, Michel Robert, Joseph Neal, Kimberly Smith, Mike Nelson, Pooja Panwar, Doug Robinson, Doug Hitchcox, Louis Bevier, Magnus Robb, Julien Rochefort, Patrick Franke, Tom Reed, Steve Kolbe, Dave Slager, Marilyn Westphal, Walter Szeliga, Ken Blankenship, Joan Collins, and all the other growing number of Loxiaphiles for continued input to an evolving and spirited discussion about crossbills. A special thanks to Michael O’Brien for edits and comments to Crossbill primers we’ve written!

Credits

The below recordings are credited to The Macaulay Library at The Cornell Lab of Ornithology:

Type 1_flight_call_ML137497 – Gregory F. Budney

Type 1_flight_call_ML22786381 – Matthew A. Young

Type 2_flight_call_kinked_ML44960 – Geoffrey A. Keller

Type 2_flight_call_unkinked_ML161299 – Matthew A. Young

Type 3_flight-call_ML68287331 – Andrew Spencer

Type 3_flight_call_ML71525571– Matthew A. Young (formerly ML136592)

Type 4_flight_call_ML68287801 – Andrew Spencer

Type 4_flight_call_ML58167 – William W. H. Gunn

Type 5_flight_call_ML138539 – Gregory F. Budney

Type 5_flight_call_ML516122 – Mark B. Robbins

Type 6_flight_call_ML42530661 – Timothy Spahr

Type 6_flight_call_aF743– Jeff Groth (Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at Berkeley)

Type 7_flight_call_aF497 – Jeff Groth (Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at Berkeley)

Type 7 https://macaulaylibrary.org/asset/590216701 Tom Johnson

Type 8_flight_call_ML134103 – Martha J. Fischer

Cassia (Type 9) Crossbill_flight_call_ML64374391 – Andrew Spencer

Cassia (Type 9) Crossbill_flight_call_ML65163941 – Jay McGowan

Type 10_flight_call_ML22786541 – Matthew A. Young (formerly ML136593)

Type 10_flight_call_ML68288161 – Andrew Spencer

Type 11_flight_call_ML50907531 – John van Dort

Type 12_flight_call_ML64320431 – Tom Auer

Type 12_flight_call_aF498 – Jeff Groth (Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at Berkeley)

White-winged Crossbill_ML103203 – Matthew D. Medler

Hispaniolan_Crossbill_12989 – George B. Reynard

Literature Cited

Benkman, C. W. 1993a. Adaptation to single resources and the evolution of crossbill (Loxia) diversity. Ecological Monographs 63: 305-325.

—-. 1993b. The evolution, ecology, and decline of the Red Crossbill of Newfoundland. American Birds 47:225-229.

—-. 2007. Red Crossbill types in Colorado: their ecology, evolution and distribution. Colorado Birds 41:153-163.

Benkman, C. W., J. W. Smith, P. C. Keenan, T. L. Parchman, and L. Santisteban. 2009. A new species of Red Crossbill (Fringillidae: Loxia) from Idaho. Condor 111: 169-176.

Centanni, C.T., Robinson, W.D., and Young, M.A. 2024. Is Resource Specialization the Key?: some, but not all Red Crossbill call types associate with their key conifers in a diverse North American landscape. Frontiers in Bird Science.

Griscom, L. 1937. A monographic study of the Red Crossbill. Proceedings of the Boston Society of Natural History 41:77-210.

Groth, J. G. 1993. Evolutionary differentiation in morphology, vocalizations and allozymes among nomadic sibling species in the North American red crossbill (Loxia curvirostra) complex. Univ. California Publications in Zoology 127: 1-143.

Hynes, D.P. and E. H. Miller. 2014. Vocal distinctiveness of the Red Crossbill (Loxia curvirostra) on the island of Newfoundland, Canada. Auk 131(3):421-433. [link]

Irwin, K. 2010. A new and cryptic Call Type of the Red Crossbill. Western Birds 41: 10-25.

Kelsey, T. R. 2008. Biogeography, foraging ecology and population dynamics of red crossbills in North America. Doctoral Dissertation, University California, Davis, December 2008.

Parchman T. L., C. W. Benkman, and S. C. Britch. 2006. Patterns of genetic variation in the adaptive radiation of New World crossbills. Molecular Ecology 15: 1873-1887.

Parchman, T. L., C. A. Buerkle, V. Soria-Carrasco, and C. W. Benkman. 2016. Genome divergence and diversification within a geographic mosaic of coevolution. Molecular Ecology 25:5705-5718.

Pieplow, N. 2007. Colorado Crossbill Types: 2, 4 and 5. Colorado Birds: 41: 202-206.

Sewall, K. B. 2009. Limited adult vocal learning maintains call dialects but permits pair-distinctive calls in Red Crossbills. Animal Behavior 77: 1303-1311.

—-. 2010. Early learning of discrete call variants in red crossbills: implications for reliable signaling. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 65: 157-166.

Spencer, A. 2009. Specimens of rare Red Crossbill types from Colorado. Colorado Birds 43(3): 187-191.

Summers, R. W., R. J. G. Dawson, and R. E. Phillips. 2007. Assortative mating and pat- terns of inheritance indicate that the three crossbill taxa in Scotland are species. Journal of Avian Biology 38: 153-162.

Szeliga, W., L. Benner, J. Garrett, and K. Ellsworth. 2014. Call types of the red crossbill in the San Gabriel, San Bernardino, and San Jacinto Mountains, southern California. Western Birds 45: 213-223.

Young M. A. 2010. Type 5 Red Crossbill (Loxia curvirostra) in New York: first confirmation east of the Rocky Mountains. North American Birds 64: 343-346.

—-. 2011. Red Crossbill (Loxia curvirostra) Call-types of New York: their taxonomy, flight call vocalizations and ecology. Kingbird 61: 106-123.

—-. 2012. http://content.ebird.org/ebird/news/recrtype/

Young, M. A., K. Blankenship, M. Westphal, and S. Holzman. 2011. Status and distribution of Type 1 Red Crossbill (Loxia curvirostra): an Appalachian Call Type? North American Birds 65: 554-561.

Young, M. A., D. A. Fifield and W. A. Montevecchi. 2012. New evidence in support of a distinctive Red Crossbill (Loxia curvirostra) Type in Newfoundland. North American Birds. 66: 29-33.

Young MA, Spahr TB, McEnaney K, Rhinehart T, Kahl S, Anich NM, Brady R, Yeany D and Mandelbaum R (2024) Detection and identification of a cryptic red crossbill call type in northeastern North America. Front. Bird Sci. 3:1363995. doi: 10.3389/fbirs.2024.1363995

Please address comments or questions on this article to the authors to Matt at may6@cornell.edu or info@finchnetwork.org, Tim at tspahr44@gmail.com, or Caleb at ctc222@cornell.edu

*Matthew A. Young, Finch Research Network, Cincinnatus, NY 13040. info@finchnetwork.org

Please think about joining Finch Research Network iNaturalist Projects:

Winter Finch Food Assessment Project/Become a Finch Forecaster (includes Evening Grosbeak): https://finchnetwork.org/the-finch-food-assessment-become-a-finch-forecaster

Red Crossbill Foraging Project: https://www.inaturalist.org/projects/red-crossbill-foraging-in-north-america

Book Link

For more on Red Crossbills and much much more, here is a link to the exciting and newly released Stokes Guide to Finches of the United States and Canada: https://www.amazon.com/Stokes-Finches-United-States-Canada/dp/0316419931

Shirt Link

For a commemorative Winter Finch Forecast shirt or a newly released Goldfinch shirt with all 3 Goldfinch species that makes for a great holiday present, see here: https://finchnetwork.org/shop

The Finch Research Network (FiRN) is a nonprofit, and was granted 501c3 status in 2020. We are a co-lead on the International Evening Grosbeak Road to Recovery Project, and have funded almost $22,000 to go towards research, conservation and education for finch projects in the last couple years. FiRN is committed to researching and protecting these birds like the Evening Grosbeak, Purple Finch, Crossbills, Rosy-finches, and Hawaii’s finches the honeycreepers.

If you have been enjoying all the finch forecasts, blogs and identifying of Evening Grosbeak and Red Crossbill call types (20,000+ recordings listened to and identified), redpoll subspecies and green morph Pine Siskins FiRN has helped with over the years, please think about supporting our efforts and making a small donation at the donate link below. The Evening Grosbeak Project is in need of continued funding to help keep it going.

Donate – FINCH RESEARCH NETWORK (finchnetwork.org