Type 12, the “Old Northeastern” Red Crossbill

By Ryan F. Mandelbaum

North America’s quintessential nomadic finch has been hiding a secret right under our noses: A previously-unidentified red crossbill call type has inhabited one of North America’s most populated regions, the northeast, all along.

From a birding perspective, the US northeast is famous for its huge cities, migratory hotspots, and hardwood forests — not crossbill-hosting conifer stands. But sound recordings from countless birders, plus a machine learning analysis, have revealed the presence and ecology of the newest crossbill call type: Type 12, the Northeastern red crossbill.

First, a reminder on call types: When it comes to taxonomy, we usually break species into subspecies, or distinct populations of species that inhabit a specific location and begin to evolve their own unique traits. But red crossbills don’t always follow the taxonomic rules that humans write for them — many groups of these finches aren’t tied to a specific location year after year, and when conifer cone crops fail in their core zones of occurrence, they will instead rove around vast areas in search of better cone crops. Therefore, we have a different way of keeping track of these populations, the call types.

Pioneering work by biologists Jeff Groth, Craig Benkman, and Tom Hahn demonstrated that red crossbills sort themselves into call types based on subtle auditory differences in the “kip kip” sounds they make when calling out to each other in flight. Call types act much like subspecies, predominantly breeding with members of the same call type. Different call types have begun to evolve distinct traits, especially varying bill sizes to tackle different kinds of conifer cones. But unlike subspecies, call types aren’t linked to a distinct breeding location every year.

Until now, scientists have identified eleven call types in North America, one of which, the Cassia Crossbill, has been elevated to its own species. The Northeastern red crossbill is the twelfth.

Ornithologists have long suspected that a unique call type was inhabiting the northeast. While FiRN founder Matt Young was working as a collections management leader at Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Macaulay Library, he and fellow FiRN founder Tim Spahr noticed northeastern recordings of birds categorized as very rare variants of the west coast’s Type 10 red crossbill dating as far back as 1962. When viewed on the spectrogram, or a graph depicting the frequencies of the call, most type 10 bird’s calls had an upsweeping shape. But these northeastern birds instead looked like someone had tacked a steep downward line at the end of the usual type 10 call.

The Finch Research Network has been busy working with eBird and Macaulay Library making sure recordings are correctly assigned to the right call type. But to see and hear more examples click here:

https://search.macaulaylibrary.org/catalog?taxonCode=redcro10&view=list&mediaType=audio

https://search.macaulaylibrary.org/catalog?taxonCode=redcro39&view=list&mediaType=audio

Northeastern birders have increasingly captured recordings matching this variant. Today, it appears with regularity in the area, with birds matching this type flooding the northeastern coast in the winters of 2020-2021 and this winter (2022-2023).

In a new paper, researchers performed a machine learning analysis on the Type 10 and Type 12 birds with the help of BirdNET, a research project that uses artificial intelligence and neural networks to learn and categorize avian vocalizations. They determined that birds could consistently be grouped into two different types.

How did this call type go unnoticed for so long? Well, there was a reasonably common red crossbill population present in the northeastern U.S. and eastern Canada reported in the 19th century, called Loxia curvirostra ssp. neogaea by Griscom in 1937 and Dickerman in1 987 (Figure 2). Dickermen wrote about how this was the “Old medium-billed Northeastern Crossbill”. These birds became scarcer and eventually rare as logging cleared much of the northeast’s conifer forests 100-125 years ago.

Researchers had a hunch that the type was still around, and the ecology and behavior of the Type 12 seems to match that of the previously-described neogaea subspecies (Figure 2). The maturation of native forests, and the re-planting of forests to conifers across the region could be responsible for the rebound of this call type.

Based on research, we now know that in most years, you can find Type 12 in the conifer forests of the northeast, such as in Ontario’s Algonquin Provincial Park, New York’s Adirondacks, Northern New England, and Canada’s Maritime Provinces, which we call its Core Zone of Occurrence. Its Secondary Zone of Occurrence, where it occurs less often but breeds in some years, includes southern New York and the northwestern Great Lakes region.

This bird regularly migrates southward, especially along the coast to Cape Cod, Long Island, New Jersey, Delaware, and into the Upper Midwest. We call these areas the Primary Zone of Irruption. Some birds travel further — the Secondary Zone of Irruption. We now consider birds appearing elsewhere as vagrants, especially in the west.

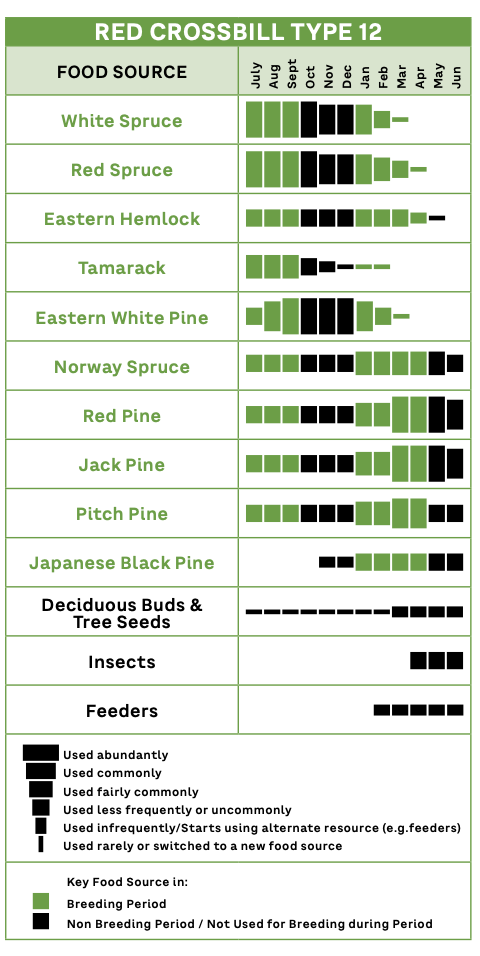

This crossbill appears to have a medium-sized bill fit for the high conifer diversity but low conifer density of northeastern North America. Breeding birds feed primarily on the cones of red and white spruce and red, jack, and white pine. They’ll also go for pitch pine, tamarack, Eastern hemlock, and ornamental conifers like Japanese black pine, blue spruce, and Norway spruce. Birds in southern New York and Pennsylvania have even bred in Norway Spruce plantings.

This research demonstrates that red crossbills continue to pose an interesting puzzle to biologists — while also highlighting the importance of birders and citizen scientists to science. We hope that this research encourages birders to continue exploring conifer habitats. And of course, keep recording those crossbills!

A similar article appeared in the winter 2023 FiRN newsletter first released in mid December 2022. To get the most up-to-date FiRN news and exclusive finch research updates, join here: https://finchnetwork.org/product/membership

Here is a Foraging Chart through the cone cycle year for Type Red Crossbill.

Type 12 Foraging Chart from Stokes Guide to Finches of United States and Canada (for more of these please see book)

Please address comments or questions on this article to may6@cornell.edu or info@finchnetwork.org or tspahr44@gmail.com

Cover Photo of a Pair of Type 12 Red Crossbill Adirondacks, NY March 2022. Photo Credit Matthew Young

Any use or repurpose of information in this article need be approved by the authors and the Finch Research Network.

Book Link

For help with Finch ID and much much more, here is a link to the exciting and newly released Stokes Guide to Finches of the United States and Canada: https://www.amazon.com/Stokes-Finches-United-States-Canada/dp/0316419931

The Finch Research Network (FiRN) is a nonprofit, and has been granted 501c3 status. FiRN is committed to researching and protecting finch species like the Cassia Crossbill, Evening Grosbeak, finches of Hawaii (aka the honeycreepers) and more. The Evening Grosbeak has declined 92% since 1970. We are fundraising around an Evening Grosbeak Road to Recovery project in addition to a student research project, so please think about supporting our efforts and making a small donation at the donate link below.

Donate – FINCH RESEARCH NETWORK (finchnetwork.org)

We can also be found on FB, Instagram and Twitter at https://www.facebook.com/thefinchmasters and also on FB at Finches, Irruptions and Mast Crops.