By Ryan F. Mandelbaum and Matthew Young:

A few species stole the show of this year’s incredible Eastern finch superflight—it’s hard to miss the plump evening grosbeaks or enormous flocks of Pine Siskins descending upon feeders, after all. However, it’s also been a banner year for a finch you might not have heard much about; the Purple Finch.

Purple Finches don’t occupy quite the same boreal niche as finches like the Evening Grosbeak or White-winged Crossbill. The irruptive Eastern subspecies of the Purple Finch instead inhabits moist coniferous and mixed coniferous-deciduous forests in Canada, the Northeastern, United States, and into the Appalachian Mountains to Virginia. Approximately every few years, they march southward in numbers occasionally to the Gulf Coast. But this year, they put on a show just like the rest of the finches, thanks in part to the ongoing spruce budworm outbreak in the boreal forest.

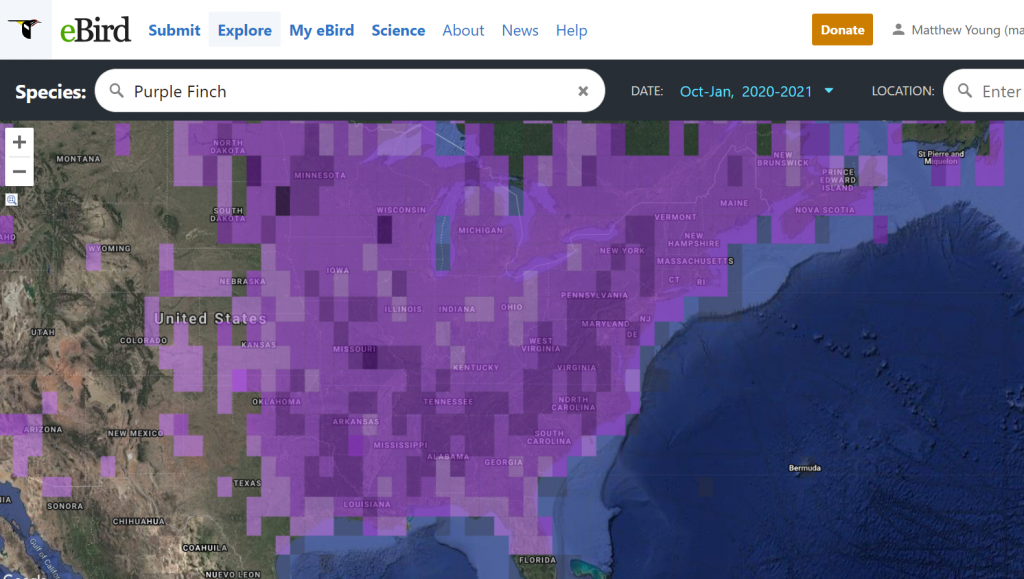

Perhaps due to their more regular and widespread occurrence, and due to the remarkable records of other winter finches, you might have overlooked this year’s notable Eastern Purple Finch flight. This year, Eastern Purple Finches marched southward prior to the rest of the irruptive finches beginning in the late summer alongside the red-breasted nuthatches, with the first Gulf Coast record coming in late October. By the end of 2020, they had become a frequent sight deep into the Southeast. Remarkable records of the eastern subspecies included birds in Arizona in October, Colorado in November, and New Mexico in November and December. We’re obviously excited about the Western birds as well, but the “Western” Purple Finch is a much more resident subspecies.

Purple Finches have a generalist feeding ecology, consuming fruits, seeds, and insects. But this year, they were perhaps the beneficiary of the same forces that sparked large numbers of eastern Evening Grosbeaks: the large outbreak of spruce budworm in the boreal forest. Purple Finches had high breeding success due to the excess of food (and the fact that budworm spraying operations were scaled back due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic). With poor seed crops to the north and budworm larva dormant for the winter, the finches were faced with a lack of food, and irrupted southward in numbers much earlier than usual. One point count completed by Matthew Gingerich between Oct 16 to Nov 19, 2020 from the western edge of the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia tallied 1,168 migrant Purple Finches. Meanwhile, the Cape May Morning Flight Songbird Count in New Jersey recorded over 1,000 Purple Finches in just two days, on October 25 and October 26, 2020. These extreme counts were likely overlooked due to their coincidence with this year’s Pine Siskin mania.

We hope you’ll stock your feeders with black oil sunflower seeds as these birds continue to seek refuge while winter wears on, and perhaps you’ll have a chance to see some more in the spring as they return north to breed one again.

Photo Credit Jay McGowan

FiRN is a nonprofit, and has been granted 501c3 status. FiRN is committed to researching and protecting these birds and other threatened finch species like the Evening Grosbeak and Rosy-finches, and if you have been enjoying all the blogs and identifying of Red Crossbill call types, redpoll subspecies and green morph Pine Siskins FiRN has helped with, please think about supporting our efforts and making a small donation at the donate link below.

For Purple Finch vs House Finch ID help, please see this video by Badgerland Birding.