A Crossbill’s Guide to Conifers of the Eastern Forest

by Matthew A. Young and Ryan F. Mandelbaum

How do you find a crossbill in eastern North America? Well, you have to know what’s on the menu. And, like a restaurant, if you want to know what’s on the menu, you need to know what’s in season. For crossbills, those seasons follows the cycles of conifer cone crops.

An Introduction to Crossbills (updated to reflect addition of Type 12)

Evolution designed the crossbill’s crossed beak for one thing: eating the seeds out of conifer cones. Their beaks act like crowbars, allowing them to push the scales of cones aside and take the seed out. This seed is usually wrapped in a paper-like coating, which the birds remove with their beak and tongue.

Finding crossbills, first and foremost, means finding stands of cone-laden conifers. But you can tweak your odds by knowing the specific conifers, when their cones will be on the menu for crossbills, and the details of the crossbill’s cone cycle year around which they schedule their lives. That cycle year starts roughly around the 1st of July, when cone crops for the year have mostly developed and have started to ripen.

These red-and-yellow finches are especially numerous in the western half of North America, where vast, elevationally stratified stands of pines, spruces, hemlocks, douglas-firs, or other conifer trees keep them well-fed. There is a lower density of conifers in eastern North America, so it’s often assumed that crossbills are absent or rare. However, what the east lacks in quantity it makes up for in variety of conifer species, which still allows crossbills to live there.

We’ve put together this guide so that new crossbill fans in the eastern US can start to find these birds on their own, while fanatics can polish their craft. We’ve included an intro to the kinds of crossbills present in this region, plus the kinds of trees they eat with a few comments what they prefer from season to season.

Know your Eastern Crossbills

You can find two species of crossbills in the eastern US, red and white-winged, with a variety of red crossbill “call types.” While white-winged crossbills comprise a single species, red crossbills consist of at least 11-12 different sub-populations in North America, and these sub-populations are better known as call types, which are told apart by subtle differences in their bill shape (especially bill depth, which is most heritable) and the calls they make in flight. Their various bill shapes allow them to associate with various conifer species, especially in the western US.

White-winged crossbill: Small billed, getting their namesake by their distinctive white-barred black wings. Earlier in the cone cycle year, their small bills keep them to softer-coned trees like tamarack, white spruce, and red spruces. When food is depleted in the late winter/early spring, they’ll use black spruce, and occasionally they use Norway spruce as well. They will feed on hemlock readily, but it’s not used during breeding events as it doesn’t meet the energetic requirements needed for nesting. Any other conifers are only used during years when birds are scrambling to find any food for survival. The white-winged crossbill also doesn’t have the jaw musculature the Red crossbills has, and it therefore is more limited in what it can efficiently feed on to meet the energetic requirements for breeding.

Type 12 (Formerly “Eastern Type 10”) “Northeastern” Red Crossbill: The most common call type in the northeast in the Adirondacks, New England, and Maritime provinces. It also is fairly commonly encountered west to the western Great Lakes. Having what appears to be a more medium sized bill gives the Type 12 the ability to feed on a wide variety of conifers from soft-coned conifers of spruce, hemlock, and tamarack to hard-coned pines of red, jack, and pitch. They’ve been documented utilizing red, white and Norway spruce, tamarack, and jack, red, pitch and eastern white pines for nesting. This past winter-spring 2022, this type even bred abundantly in the planted Norway spruce and red pine plantations of central and southern New York and northern Pennsylvania for the first time. It is quite the generalist!

Type 1 “Appalachian” Red Crossbill: This is the most common call type in the Appalachians from central New York to Georgia and Alabama. Can also be found some years in small numbers from New England, Adirondacks, and Algonquin PP. The medium bill allows them to feed on a wide variety of soft-coned conifers and the semi-soft coned eastern white pine, but this type doesn’t seem to feed much on the harder pines like red, jack and pitch pines like the “Type 12 (formerly known as “eastern Type 10”) does. It readily forages and breeds in Norway spruce some years in central and southern New York as well.

Type 2 “Ponderosa Pine” Red Crossbill: Probably the most widespread type in America, and most eclectic in diet. It would be perhaps better named the Eclectic Crossbill. It is more concentrated in the west but found annually in small numbers in the East, sometimes as breeding birds, rarely to even larger numbers during irruptions. Large bills allow them to feed on hard-coned pines that other call types like types 1 and 3 mostly avoid.

Type 3 “Western Hemlock” Red Crossbill: This is a western call type, but it’s also highly irruptive and shows up with some regularity in the East, approximately every 3-5 years—and has bred here a number of times. Small bills typically keep them to softer and small-coned white and red spruce, and eastern hemlock, thus mostly avoiding hard pines and even to some extent softer-coned conifers Norway spruce or Eastern white pine. Because of size of cone, Norway spruce acts like a hard pine in that the seeds aren’t that accessible until later in the crossbill cone cycle year as fall turns to winter.

Type 10 “Sitka Spruce” Crossbill: Primarily a western call type found in the outer coastal Sitka Spruce forests, but is occasional in the east likely irrupting eastward with Type 3. The further west you go into the western Great Lakes the more common it can be. Is a small to medium crossbill call type (smaller than the now known Type 12) that overlaps in diet with type 12 and other crossbills found in the east. In short, it will feed on various pines, spruces and hemlocks.

Type 8 “Newfoundland” Red Crossbill: Newfoundland has an endemic and threatened crossbill call type, never recorded away from Newfoundland or Anticosti Island, Quebec. It has a large bill allowing it to feed on a variety of conifers, but possibly specializes on an island-adapted black spruce.

Other Call Types found in the East:

Type 4 can be relatively common in the western Great Lakes some years, and is also pretty generalized in diet as a medium-billed crossbill. Given the variety of conifers, it’s no coincidence that medium-billed crossbills are the most common bill-sized crossbill found in the east. Type 5 is a vagrant in the east.

Know Crossbills By Knowing Cones

Crossbills will not just feed on any cone—cones must be ripe enough that the seeds are ready to eat, but not necessarily open enough that the seeds will fall to the ground. Birds prefer cones still attached to the tree, but may feed from cones fallen to the ground if food is scarce. In this guide, we describe what conifers are available in the east, how crossbills species and how the different call types shift their diet through the crossbill cone cycle year.

Conifer trees in North America produce cones in a cycle that begins in May and June and start to ripen for crossbill consumption around the first of July. Crossbills will time one of their breeding cycles to match up with this time period when cone crops are developing and starting to ripen. If there’s enough available food on their preferred trees, and this means even green cones (on white, Engelmann or red spruce), then crossbills will begin breeding shortly thereafter, with this first breeding cycle extending from about July 1 to early September for the red crossbill call types and July 1 into October for the white-winged crossbill. The more pliable a conifer cone, the easier time a crossbill will have feeding on green cones.

Once the young have fledged, the birds will go looking for food stores once again if needed, but if the crop is “bumper” enough they can remain to nest again in the same area months later, even in winter when there’s feet of snow on the ground and sub-zero temperatures. If there’s not enough food, they’ll move and switch the next available conifer with accessible seed that will meet first, survival requirements, but hopefully another round of breeding. If there’s no food available on any of the trees in the area, they’ll “irrupt” en masse to travel further afield to find food. If they do find a large new food source, they’ll breed once again.

Birds have wings and minds of their own, so these rules aren’t hard-and-fast—and crossbills will also eat insects, lichen, deciduous tree seed, buds, and even seed from bird feeders in the absence of cones, especially in spring as temperatures begin to warm and food is depleted. But it takes a good cone crop to consistently support a breeding population.

So, if you want to find crossbills, you have to know your trees. Below we’ve compiled a list of conifer trees found in northeastern North America, with notes on where the trees’ seeds sit on a crossbill’s preference list. We’ve also included a few other relevant trees that crossbills may visit during irruptions.

Trees Preferred by Any Crossbill

White Spruce (Picea glauca)

Height: 50-100 feet or more

Appearance: Conical or cylindrical, usually thinner in profile but denser in foliage than a red spruce, and thicker with more foliage than a black spruce, kind of a halfway between the two. Limbs don’t have quite the same upward-facing appearance and are less spaced out than those of a red spruce, giving it a scruffier, fuller, more cylindrical look. Ornamental white spruces typically appear shorter and more conical than wild white spruces, which can be rather imposing.

Bark: Pale gray-brown and scaly.

Leaves: Short, spiny, four-sided and pale-green growing directly from the branchlet, around ½ inch long.

Cones: Pale brown cylinders, 1 to 2 ½ inches long, which hang downward with thin, smooth scales. More elongated and thinner than red spruce and black spruce.

Range and habitat: White spruces grow across the boreal forest, from Alaska to Quebec and south to Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, and New England as far south as northern New York (it is a plantation tree in central NY), with an isolated patch in South Dakota’s Black Hills. White spruces have become a popular ornamental tree and appear in cemeteries, parks, yards, and other plantings.

Tasting and Timing Notes: These trees are extremely well-suited for growing in the boreal forest, appearing further north than any other tree in North America, nearly to the Arctic Ocean. They’re also a favorite food of spruce budworm after Balsam fir. They have very pliable cone scales, and therefore will drop seed the earliest, often by the fall except in the best bumper crop cone years. During only the best white spruce bumper crop years they can remain in an area and nest into late February-early March.

This soft-coned conifer develops seed in summer and the cones ripen right away. Find yourself in an area with lots of cone-laden white spruce and you should definitely open your eyes and ears—these small cones are the most popular crossbill munchy for all eastern crossbills, especially the white-winged crossbill.

Red Spruce (Picea rubens)

Height: 60-120 feet or more.

Appearance: Conical or cylindrical, often with wide, spaced-out, upward-curving branches

Bark: Grayish brown and flaky, revealing red-brown patches.

Leaves: Short, curved, four-sided lighter green needles growing directly from the branchlet, around ½ inch long.

Cones: Small to medium and squat reddish-brown cylinders, up to 2 inches long which hang downward. Smooth, thin scales. Cones are more oblong than white or black spruce.

Range and habitat: The northeast, from Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island west through New England to upstate New York, with patches south in the Appalachian Mountains to North Carolina and west to Algonquin Provincial Park, Ontario.

Tasting and Timing Notes: Red spruce occurs naturally only in northeastern North America and south along the spine of the Appalachians, and its height and broad crown give parts of the Appalachians, Adirondacks, and White Mountains a characteristic appearance. Its numbers declined heavily due to acid rain, though there appears to be some resurgence. It’s popular with spruce budworms, too—meaning that in the summer, it’s worth checking red spruces for budworm-loving birds like evening grosbeaks and Cape May warblers.

This soft-coned conifer develops seed in summer and the cones ripen right away. Its small cones make it a prime crossbill meal in summer and fall for both crossbill species, but moreso for red crossbill types 1, 3 and eastern 10—its cone scales are tougher than white spruce, thus making it more readily utilized by the red crossbill, which has a stronger jaw than the White-winged. During only the best red spruce bumper crop years they can remain in an area and nest into March.

Trees Most Heavily Preferred by White-winged Crossbills

Tamarack (Larix laricina)

Height: 30-60 feet, often shorter.

Appearance: Conical, occasionally quite triangular. In fall, they stand out against other conifers with their bright yellow needles, which they lose in the winter— larches are deciduous conifers.

Bark: Flaky and gray to reddish brown as it ages, with deeper red-purple bark underneath.

Leaves: 1-inch spines, arranged in starbursts of 10-20. Bright green in summer, turning yellow in autumn.

Cones: Very small cones, wide and less than an inch long, giving them a rose-like appearance.

Range and habitat: Alaska, then east of the Canadian Rockies to Newfoundland and Labrador, south to the Great Lakes and New England and appearing in patches along the southern Great Lakes through Pennsylvania and New Jersey. Often found in wet areas, such as alongside black spruce in sphagnum bogs and fens.

Tasting and Timing Notes: There are few boreal sights as striking as these deciduous conifers painting the forest yellow in the autumn. This soft-coned conifer develops seed in summer and cones ripen right away. Crossbills like it, especially white-winged crossbills in summer and fall who can easily access the tiny cones. Small and medium billed red crossbills (Type 1, 3 and 10) utilize them, even occasionally for nesting, but this species isn’t a major player most years for red crossbills. Some northern areas contain pure stands of tamaracks, appearing like tree boneyards in the winter. Tamaracks serve as good habitat for boreal birds like spruce grouses, boreal chickadees, black-backed woodpeckers, and more.

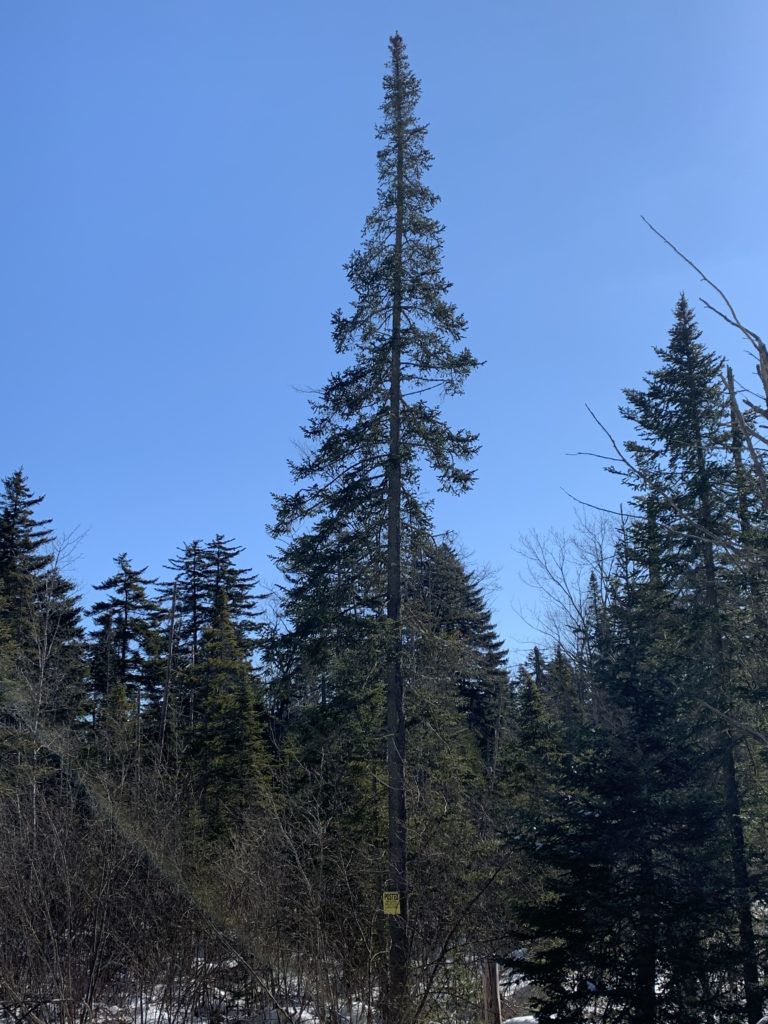

Black Spruce (Picea mariana)

Height: 15-50 feet, sometimes up to 100 feet.

Appearance: Thin, straight, and scruffy, often with needles concentrated at the top, giving it a truffula tree-like appearance.

Bark: Dark and brown, flaky.

Leaves: Short, spiny, four-sided dark green needles growing directly from the branchlet, ¼ to ½ inch long.

Cones: The smallest cones of North America’s spruces, ½ to 1 ½ inches long and squat, often spherical. Very round or barrel-shaped. Brown, thin scales. Concentrated toward the top. Cones are semi-serotinous, and therefore trees can hold cones, even with seed, for a couple years.

Range and habitat: Black spruces grow across the boreal forest, from Alaska to Newfoundland and south to the upper Midwest, Northern New York, and New England plus parts of northeastern Pennsylvania. Can be found in a variety of areas, often in pure stands, though stereotypically form a core component of sphagnum bogs alongside tamarack.

Tasting and Timing Notes: Black spruce could be the arboreal mascot of the boreal forest, and makes up a core component of sphagnum bogs and other cold-weather coniferous areas. These trees are a pioneer species, seeding right after fires and serving as the first trees to grow in bogs. Its cones are semi-serotinous, meaning some of their cones are encased in a jell and only open enough for seed to be accessible during the hottest heat waves or fire—this makes it so some trees hold seed most years, thus making it a key species utilized by white-wings during the spring months when food becomes most limited. The core of its range is north of where most red crossbills are found, and so it isn’t utilized by red crossbills as much. It is susceptible to spruce budworm, but not as much as other conifer species. Crops form in spring but don’t really ripen until late winter and spring.

Trees preferred by Red Crossbills

Eastern White Pine (Pinus strobus)

Height: 50-80 feet tall but can grow to over 150 feet, and specimens often stand out as some of the tallest trees in the Eastern woods.

Appearance: Tall, straight trunk with a crown of widely-spaced horizontal limbs, with long, limp needles giving it a soft appearance. Due to its height, it may miss limbs on one side of the tree due to wind damage.

Bark: Grayish to brown with vertical fissures.

Leaves: Floppy and soft, 3-5 inch blue-green needles, five per cluster.

Cones: Long cylinders, 4-8 inches long and about an inch wide when closed, light brown when ripe and often covered in sticky resin. Large and wide but thin, pliable scales.

Range and habitat: From the Maritime provinces west through New England and Ontario to the Great Lakes states, especially Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan, and south from Pennsylvania through the Appalachians to Georgia. Typically found in humid areas with well-drained, sandy soil as part of mixed forests.

Tasting and Timing Notes: Eastern white pines are a charismatic tree of the Eastern forest, given their height and ubiquity. Their seeds and needles feed plenty of northeastern wildlife, including red crossbills. They’re a semi-soft-coned pine that ripens in two years: it forms conelets in year one, which ripen the following summer. It has larger scales than native spruce, hemlock and tamarack making them a favorable choice for medium and even larger billed crossbills (especially medium billed type 1 but also Eastern medium-billed 12 (formerly known as eastern type 10) and large-billed type 2 ) who will choose them after native spruce crops have little seed remaining. This is a go-to in August to February for medium and large-billed crossbills such as types 1, 10 and 2. Type 4 will utilize fairly easily as well when they irrupt, especially in the western Great Lakes, and Type 3 will use but after only after hemlocks and spruces have been depleted—Type 3 has the smallest bill of any crossbill in North America (including White-winged Crossbill), and therefore doesn’t have the easiest of times with the seeds in the large-coned white pine.

Eastern Hemlock (Tsuga canadensis)

Height: 100-150 feet or taller

Appearance: Tall, cylindrical or conical with short, soft, and dense needles giving it an overall fluffy look. Notice that the leader, or the topmost branch, will typically droop over.

Bark: Brown with long fissures.

Leaves: Short and flat, typically ½-inch long, green on top and pale on the bottom, arranged in rows.

Cones: Very small, short and brown, ½-inch to an inch, dark brown when ripe.

Range and habitat: From the Maritime provinces west through New England and Ontario to Wisconsin and Michigan, and south from Pennsylvania through the Appalachians to Alabama. Typically in cooler areas and capable of withstanding various soil conditions.

Tasting and Timing notes: Cones develop in spring and ripen in summer. The hemlock is a majestic, tall tree whose little cones and wide range make it a go-to for small billed red crossbills like the highly irruptive type 3, which irrupts in numbers to the east approximately every 3-5 year. Since type 3 specializes on western hemlock, it’s no surprise that they’re attracted to the only other widespread hemlock in North America. Type 1 utliizes hemlock as well, but not nearly as much as Type 3. Often holds some seed through winter during the best bumper cone crop years. These trees can live for a long time, to 500 or even 1,000 years old, but are currently listed as Near Threatened due to their susceptibility to the invasive Hemlock wooly adelgid.

Red Pine (Pinus resinosa)

Height: 60-150 feet tall

Appearance: Tall, straight-trunked pine with crown of horizontal limbs, often with a long, branchless trunk beneath the canopy. Stiff needles give it a distinctive spiny appearance, and it often appears in single-species plantations of identical size-and-shape trees.

Bark: Grayish brown with flakes revealing pinkish-red color beneath, higher up in the tree.

Leaves: Stiff, 5-7 inch long green needles grouped in twos.

Cones: 1 ½ to 2 ¼ inch round, spherical cones with thick woody scales, dark brown when ripe. Forms green cones in year one, and ripens the following year.

Range and habitat: From Maritime Provinces westward through Quebec, Maine, and New England to southeastern Manitoba, south to Minnesota and Central New York with patches in Newfoundland, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut. Typically favors well-drained soil. Widely planted by the Civilian Conservation Core in state forests of the Northeast.

Tasting and Timing Notes: You know when you’ve entered a red pine forest, with neat rows of identical pink-red barked trees lining the trail. While its cones are medium-sized, they’re also very hard. Like any pine, they have a two-year cone cycle, in that they form cones in year 1 and they ripen the following year. This appears to be a key conifer for Type 2 and Eastern Type 12, especially in late winter-early spring into early summer when conifer seed is most limited. Other crossbills will only eat them after depleting the seeds of other softer-coned conifers.. Interestingly, medium-billed Type 1 doesn’t appear to use them much, while in the large Type 4 western Great Lakes event of 2017-18, Type 4 was commonly found in red pine, and successfully nested (Brady et al. 2019).

Jack Pine (Pinus banksiana)

Height: 30–70 feet, but can be shrubby in poor soil.

Appearance: Generally a smaller tree with a somewhat scraggly or gnarled appearance and shorter needles.

Bark: Pale, gray-brown bark with deep fissures.

Leaves: ¾ to 1 ½ inch twisted green needles in pairs.

Cones: Curved like a horn, two inches, pale yellow-gray when ripe, with thick, almost waxy-looking scales.

Range and habitat: In the east, jack pines live further north than most other pines, from the Maritime provinces through Maine and Quebec to the northwest territories, patchy in New York and west into parts of the upper midwest. Large homogenous stands of stunted jack pine grow in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Ontario.

Tasting and Timing Notes: Jack pines’ hard cones are readily utilized by medium-billed eastern Type 12 (and type 4) and likely are a good food source for larger-billed crossbills such as Type 2 crossbills in spring and summer. They will nest in spring and summer using Jack Pine. Of course, if you’re in stunted jack pine forests in Michigan, Wisconsin, or Ontario, you have rarer birds to look for than red crossbills—that’s where Kirtland’s warblers breed.

Pitch Pine (Pinus rigida)

Height: Small to medium, 20-100 feet.

Appearance: Gnarly and irregular in shape, sometimes with dead branches still attached.

Bark: Thick and irregular brown plates, often with needles appearing to grow directly out of it

Leaves: Thick, 2 ¼ to 5 inches long and arranged in groups of three.

Cones: Squat and spherical or slightly conical, 1 ½ to 2 ¾ inches long with small spines on the end of each thick, woody scale.

Range and habitat: Pitch pines grow where other plants won’t, in acidic or sandy soil from southeastern Maine through the Appalachians with patches along the northeastern coast and the St. Lawrence river valley. It’s the predominant tree in the pine barrens of New Jersey and Long Island.

Tasting and Timing Notes: Hard-coned pine eaters like Type 12 and type 2 red crossbills will eat pitch pine when available, especially in spring and summer. Additionally, red crossbills will occasionally irrupt into pitch pine barrens along coastal Massachusetts, NY and NJ in the absence of food elsewhere; Type 12 will occasionally nest at these locations in spring.

Scotch (or “Scotts”) Pine (Pinus sylvestris)

Height: Up to 100-150 feet or more

Appearance: This tree stands out among conifers with large size, gnarled shape, smooth and tan bark, and leaves concentrated at the crown.

Bark: Grayish brown at the base, flaking away to orange closer to the top

Leaves: Blue-green to green needles, 1-2 inches long and grouped in sets of two but sometimes longer and in larger groups.

Cones: Egg shaped, 1 to 3 inches long with thick, woody scales.

Range and habitat: Native to northern Europe and Asia, but introduced in the United States where it mixes with other pines in the northeast.

Tasting and Timing Notes: Scotch pine is the favorite food of Scotland’s endemic crossbill, the Scottish Crossbill. However, this blog isn’t about Scotland. Like other hard-coned pines, larger-billed crossbill call types will readily feed on it when available while smaller-billed call types will choose other trees first. Type 12 and Type 2 will feed on Scotts Pine.

Japanese Black Pine (Pinus thunbergii)

Height: While it can grow to 100 feet or more in its native range, it more often appears far shorter in poor soil, around 35 feet.

Appearance: In North America, Typically appears in single-species plantings in human-altered habitats, often in coastal areas and with many dead trees mixed in.

Bark: Gray, growing darker to near black with plates on older trees.

Leaves: Green and stiff, 2 ¾ to 4 ¾ inches in groups of 2 that often appear to point upward.

Cones: Conical and brown, 1 ¾ to 2 ¾ inches with thick and squat woody scales.

Range and habitat: These salt-tolerant introduced trees were once a popular ornamental planting, especially on Long Island and New Jersey, where they still appear in numbers in some coastal parks and on roadsides. Die-off has happened in the last few decades.

Tasting and Timing Notes: Winter irrupting Type 12 (and sometimes type 1, 3, and even 4) red crossbills in the East are often forced through the famed migration hotpots of coastal New York and New Jersey such as Jones Beach and Cape May. Here, they encounter and often choose to feed in the large coincidentally-placed Japanese black pine plantings.

Norway Spruce (Picea abies)

Height: 115–180 ft

Appearance: Conical, with limbs curving upward while stems and needles seem to droop. Often seen as single ornamental trees in yards, parks, and cemeteries, though in some places (central New York, for example) appears in organized plantings. This is a common choice for large, outdoor Christmas trees, such as in Rockefeller Center.

Bark: Pale brownish gray and scaly.

Leaves: Stiff, ½-inch blunt-tipped green needles, arranged around branchlets that droop downward.

Cones: Long and sausage shaped with short and thin but stiff and wide scales, 3 ½ to 7 inches, pale red-brown when ripe.

Range and habitat: Native to Europe, but widely introduced as an ornamental tree throughout the northeast. Conifer forests dominated by Norway spruce were planted by the Civilian Conservation Corps throughout Pennsylvania, New York, and New England in the 1930s to combat soil erosion.

Tasting and Timing Notes: Norway spruces may be introduced, but they’re still on the menu for crossbills, especially for the red crossbill when there’s an absence of other native favorites. Norway spruces are especially popular for irrupting crossbills, who may not have access to other food sources; if you hear that crossbills are on the move outside of the boreal forest, your local cemetery or state forest Norway spruce plantings might be a good place to check. The very large cones hold seed for a year or two, and large enough stands of Norway spruce can support populations of breeding red crossbills, especially Type 1 type 12.

Blue Spruce (Picea pungens)

Height: Up to 75 feet.

Appearance: Conical, Christmas-tree shape with distinctive blue-tinged needles on upward-curving branches. Often seen as single ornamental trees in yards, parks, and cemeteries.

Bark: Scaly and grayish

Leaves: Stiff, 1-inch blue-green needles arranged radially around upward-curving branches.

Cones: Sausage shaped with thin but stiff scales, up to 4 inches long, pale red-brown when ripe.

Range and habitat: Native to the Rocky Mountains, but widely introduced as an ornamental three throughout the United States and planted to reduce soil erosion in some areas of the northeast.

Tasting and Timing Notes: Think Norway spruce, but smaller and blue. Type 5 like this species in the west in summer and fall and occasionally even into winter during the best bumper crop years.

Balsam Fir (Abies balsamea)

Height: 40-60 feet.

Appearance: Conical, with a long skinny leader sticking out of the top. Can be mistaken for black spruce, but notice that leaves cover the whole plant rather than concentrating around the top. Also notice cones which grow first as brown stems, looking like small mushrooms sticking out of the tree’s crown. Among the most common trees in the boreal forest and a popular household Christmas tree in the east.

Bark: Gray, smooth on younger trees and fissured or scaly on older trees.

Leaves: Flat needles, around ½ to 1 inch long

Cones: Cylindrical, 1 ½ to 3 ¼ inches long, brown when ripe. Extremely short and soft scales.

Range and habitat: This is the hearty tree that gives much of the boreal forest its signature look. East from Newfoundland and Labrador as far west as Alberta, south from the upper Midwestern states and New York’s Adirondack mountains with patches in the highest peaks of the Appalachians in Virginia and West Virginia. The closely related fraser fir, treated sometimes as a species and sometimes as a subspecies, replaces the balsam fir further south in western Virginia, eastern Tennessee, and North Carolina). Prefers cold habitats, and can grow in various soil types which impact the appearance of the tree.

Tasting and Timing notes: The balsam fir is the sure sign of good boreal habitat, but the weak, flaky cones and resinous seeds place it low on the crossbill preference list. Crossbills occasionally will eat it and may perch atop balsam firs, but you should note that if you encounter a large stand of balsam firs, then spruces, pines, hemlocks, and tamaracks are probably either mixed in or nearby and should be explored first. Note that balsam fir is the main host of spruce budworm, and therefore it’s good to check them in summer for budworm-loving finches like Evening Grosbeaks and Pine Siskins and warblers like Bay-breasted Warbler and Cap May Warbler.

Northern White Cedar, aka Arborvitae

Height: Typically short to 40 feet tall, but occasionally taller to 150 feet.

Appearance: Conical, bright green with dense foliage.

Bark: Grayish brown to deeper brown, and flaky in long, peelable thin strips.

Leaves: Distinctive bright green, flat, scaly and fractal-shaped

Cones: ½ inch long and tulip-shaped, appearing in clusters. Pale brown when ripe.

Range and habitat: From Maritime provinces west to Manitoba, south through the upper midwestern states and central New York with small patches in the Appalachians, Connecticut, and elsewhere. Common ornamental planting throughout the United States.

Tasting and Timing Notes: If you’ve found a stand of native white cedars, it’s likely you’re already in good crossbill habitat. Crossbills usually don’t go after white cedar cones specifically, but may hang out in cedar trees or incorporate pieces of cedar bark into their nests. If you run into a random planting of arborvitae far from any other conifers, you’re better off searching somewhere else. Pine Siskins do enjoy their seed though!

Southern pines taken by Type 1 and irruptive red crossbills

The above trees mostly comprise the Northeastern forest. However, resident type 1 crossbills and other irruptive crossbills inhabit the Appalachians and surrounding areas as far south as Alabama. Here, they encounter a few hard-coned pines not present in the Northeast. We’ve chosen just a few to highlight (leaving out the southernmost trees a red crossbill is least likely to encounter).

Table Mountain Pine (Pinus pungens)

Height: Generally short, up to 40 feet.

Appearance: Short, round, and rather gnarly, typically appearing in distinctive habitat.

Bark: Scaly and rich brown

Leaves: Yellow green and 1 ½ to 2 ¾ inches long in bundles of 2 or 3.

Cones: Spherical, 1 ½ to 3 ½ inches, brown to gray brown with distinctive spines on each thick, woody scale.

Range and habitat: This distinctive pine is restricted to high elevation rocky slopes of the Appalachian Mountains.

Tasting and Timing Notes: Like other hard-coned pines, this is not a good choice for irruptive smaller-billed crossbills, and Type 1 has a very hard time feeding on this Appalachian pine. It can be a go-to for the large-billed Type 2 crossbill in spring.

Virginia Pine (Pinus virginiana)

Height: 20-60 feet, but can grow taller.

Appearance: Appears tall and straight with parallel branches but small scraggly needles that leave lots of the tree exposed.

Bark: Red and brown with small scales.

Leaves: Yellow green, 1 ½ to 3 inches long in twisted pairs.

Cones: Beet-shaped and small, 1 ½ to 2 ¾ inches long. Reddish-brown when mature with relatively thin and long, woody scales.

Range and habitat: Long Island and south through the Appalachians and surrounding areas to Alabama and parts of Mississippi, typically in poor, clay soil.

Tasting and Timing Notes: A hard-pine like jack, red, pitch, Table Mountain and the pines of the southern United States. Seems to be a go-to food of medium-billed Appalachian Type 1 red crossbill and large-billed type 2s in late-summer to spring.

Loblolly Pine (Pinus taeda)

Height: Can grow quite tall, up to 100 or even over 150 feet

Appearance: Large and slender with branches concentrated densely around the crown.

Bark: Pale, clay colored with long plates and deep fissures.

Leaves: Green needles from 4 ¾ to nearly 9 inches long, twisted and in groups of three.

Cones: Conical, 2 ¾ to 5 inches long, with small spines on thick, long scales.

Range and habitat: This is perhaps the most distinctive pine in the south, and is the second most common tree in the US. It typically occurs in swampy or wet areas from far southern New Jersey along the southeastern coastal plain and Piedmont as far west as eastern Texas.

Tasting and Timing Notes: The red crossbill’s range map and the loblolly pine’s range map barely intersect, but where it does, type 1s (and Type 2) will feed on its hard cones. Red crossbills have nested in areas of Arkansas, Georgia and Alabama utilizing this species.

Shortleaf Pine (Pinus echinata)

Height: 65–100 ft

Appearance: Large and slender with branches concentrated around the crown, more patchily distributed than loblolly’s branches.

Bark: Pale clay-colored with large plates pockmarked with small dimples.

Leaves: Green and short, 2 ¾ to 4 ¼ long in bundles of two or three

Cones: Small—1 ½ to 2 ¾ inches long, smaller than the other southern pines, brown when ripe. Very similar to Virginia pine but typically even smaller.

Range and habitat: Wide range across the southeast from New Jersey to northern Florida and west to Missouri and Arkansas, specially the Ouachita Mountains where it inhabits wet and rocky areas.

Tasting and Timing Notes: Like other southern pines, this pine is a choice for irruptive birds and some type 1 crossbills in the deep south. They have nested in areas of Arkansas, Georgia and Alabama utilizing this species.

Some other boreal trees you might encounter:

Alder

White (aka Paper) Birch

Both alders and paper birch are loved by redpolls and siskins, but crossbills have been noted feeding on them more than a few times.

Stay tuned for more on conifers for crossbills as we try to build upon the where, how, and when to look for crossbills. And lastly, the winter finch forecast is less than a week away. Happy Finching!

All unlabeled photos were taken by Ryan Mandelbaum or Matt Young.

FiRN is a nonprofit, and has been granted 501c3 status. FiRN is committed to researching and protecting these birds and threatened finch species like the Evening Grosbeak, a species that has declined 92% since 1970. We are actively in the process of fundraising around an Evening Grosbeak Road to Recovery plan in addition to a student research project, so please think about supporting our efforts and making a small donation at the donate link below.

Donate – FINCH RESEARCH NETWORK (finchnetwork.org

Works Referenced

http://www.adirondackvic.org/Trees-of-the-Adirondacks-Tamarack-Larix-laricina.html

https://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/tree/picgla/all.html

https://www.conifers.org/pi/Picea_rubens.php

https://wildadirondacks.org/trees-of-the-adirondacks-eastern-white-pine-pinus-strobus.html

https://mortonarb.org/plant-and-protect/trees-and-plants/black-spruce/

https://www.nps.gov/shen/learn/nature/eastern_hemlock.htm

https://sprucepinefir.us/norway-spruce/

http://www.hort.cornell.edu/4hplants/Ornamentals/Spruce.html

https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/misc/ag_654/volume_1/abies/balsamea.htm

https://www.birdzilla.com/birds/red-crossbill/bent-life-history.html

https://finchnetwork.org/species/crossbills/red-crossbill-loxia

https://ebird.org/news/crossbills-of-north-america-species-and-red-crossbill-call-types/

https://ebird.org/checklist/S54969514

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pinus_thunbergii

https://www.nytimes.com/1988/04/24/nyregion/state-plans-to-end-japanese-pine-sales.html