Tracking Evening Grosbeaks with New Technology: By David Yeany II:

With such huge numbers of finches seen south of the boreal forest this winter, it’s hard to think that any of these species could possibly be declining. However, that couldn’t be farther from the truth with Evening Grosbeaks. For about 100 years, the species had regular winter irruptions into the northeastern United States. But in 2016, an Evening Grosbeak population trend assessment revealed a continent-wide decline of 92% since 1970 – the steepest among all landbirds in the U.S. and Canada. This led to the national listing of the species as Special Concern in Canada (COSEWIC 2016). Also, Partners in Flight called for the need to better understand evening grosbeak breeding ecology, irruptive movements, and population drivers to help develop conservation strategies (PIF 2016). Evening Grosbeaks are notoriously secretive when nesting and while their irruptive movements are visible on the landscape, still very little is known about linkages between breeding and wintering populations.

In Pennsylvania, Evening Grosbeaks were regular winter visitors, especially in northern counties, until the early 1990s and were even confirmed breeding in the state. The Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Powdermill Avian Research Center (PARC) banded 4,423 grosbeaks during the 1970s, but by the 2000’s only 9 grosbeaks were banded at the station. Why the decline? Possible factors include loss of mature spruce-fir forest, collision mortalities, climate change, and fluctuations in spruce budworm populations. The latter is a likely factor in the bumper crop of grosbeaks this winter, as pesticide use in some budworm outbreak areas was reduced due to the pandemic.

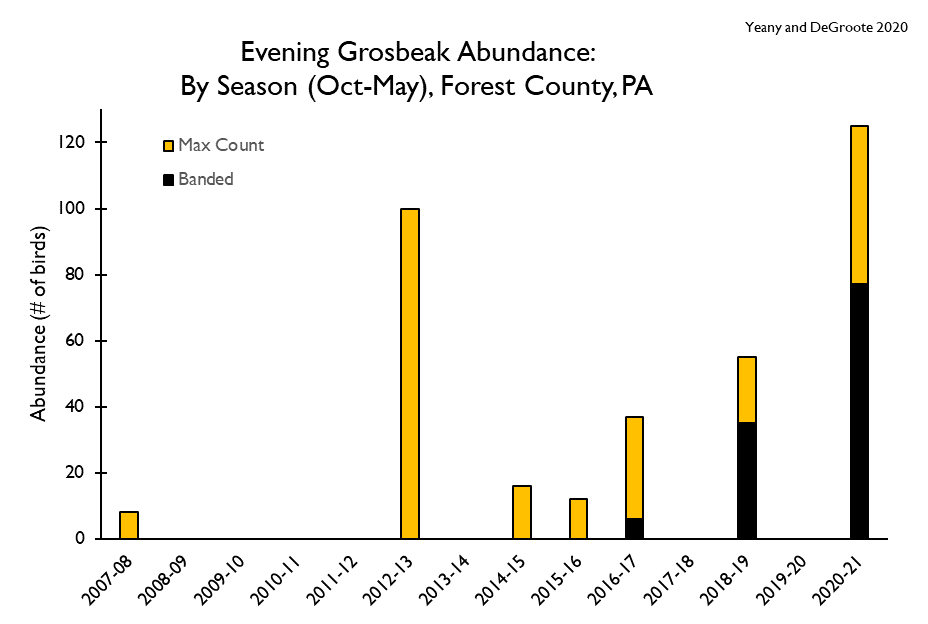

Despite the decline in PA winter Evening Grosbeak numbers, there remains a consistent population in the Allegheny National Forest (ANF) region (see Figure), with grosbeaks observed in half of the irruption seasons since 2007 (Figure 1). Seizing an opportunity, the Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program at the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy teamed up with PARC and used new tracking technologies to better understand the mysterious migration ecology, and perhaps the decline, of Evening Grosbeaks.

Now in the project’s fifth season, we began collaborating with Finch Research Network and took full advantage of this year’s historic irruption. We had a very successful effort, deploying tiny radio transmitters – nanotags – that are detected by automated radio telemetry stations. These antennas collect radio signals from the nanotags via the Motus Wildlife Tracking System. During this current irruption we tagged 56 Evening Grosbeaks at our research site in western PA.

In total, we have marked 118 evening grosbeaks with unique color-bands for identification by field observers (keep an eye out for these this spring!) and deployed 74 nanotags on Evening Grosbeaks since 2017. Our project represents the first tracking study of Evening Grosbeaks – a curious distinction for a species which is known to have irruptive migration. This project also is likely the first to deploy new solar-powered nanotags by Lotek. This gives us the potential for many years of tracking Evening Grosbeaks, with individuals known to live up to 15 years in the wild. Altogether, 40 grosbeaks have flown off with solar-powered transmitters this season.

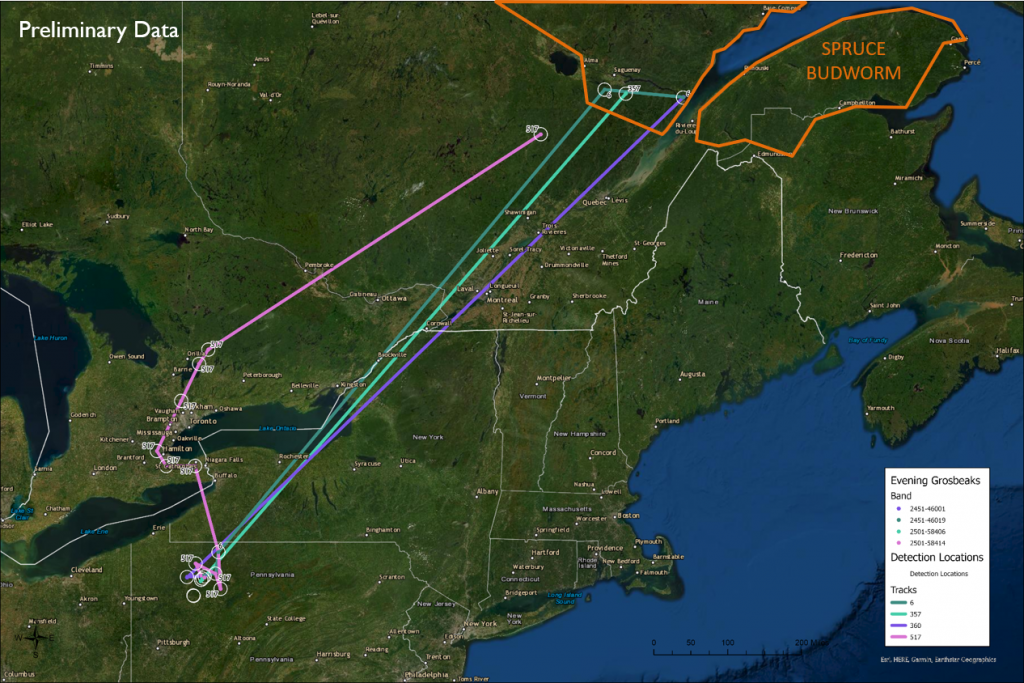

We aim to shed light on both local and landscape scale Evening Grosbeak movements during winter and migration. To date, at least 45 birds from the project have been detected or re-sighted at locations away from our western Pennsylvania research site. This includes 34 birds detected by Motus across at least 20 locations – half of which are in Canada. Local tracks show a high level of movement within the region and a high flock turnover at feeding stations, revealing that higher numbers of grosbeaks make up these winter populations than eBird observations alone would indicate. We also have tracks for four Evening Grosbeaks tagged from three separate flocks during their return flights in 2019 (Figure 2). All tracks led to an area just south of Saguenay, Quebec, where there is a known spruce budworm outbreak.

With this tracking information, we are beginning to link winter populations of Evening Grosbeaks to breeding areas with active spruce budworm outbreaks in the boreal forest. We should gain more information with Motus detections this spring about how these birds use the landscape and time their movements. In the coming years, through continued collaboration among PNHP, PARC, and FiRN we have a goal to continue tracking these finches during their irruptive movements and perhaps on the breeding grounds – all to better inform full annual cycle conservation strategies for Evening Grosbeaks.

Cover Photo Credit David Yeany II

FiRN is a nonprofit, and has been granted 501c3 status. FiRN is committed to researching and protecting these birds and other threatened finch species like the Evening Grosbeak and Rosy-finches, and if you have been enjoying all the blogs and identifying of Red Crossbill call types, redpoll subspecies and green morph Pine Siskins FiRN has helped with, please think about supporting our efforts and making a small donation at the donate link below. We plan to support student research projects and more.

Wildside Nature Tours and The Finchmasters – Finch Research Network (FiRN) are very excited to team up for our first partnership tour focusing on finch species of the Pacific Northwest! We’re really stoked about this. Its going to fun to be working with Alex Lamoreaux and Wildside Nature Tours. Let us know if you’re interested or have any questions. Read below for trip details.

For more on Evening Grosbeaks, read below: