How to Search for Breeding Crossbills

By Ryan Mandelbaum

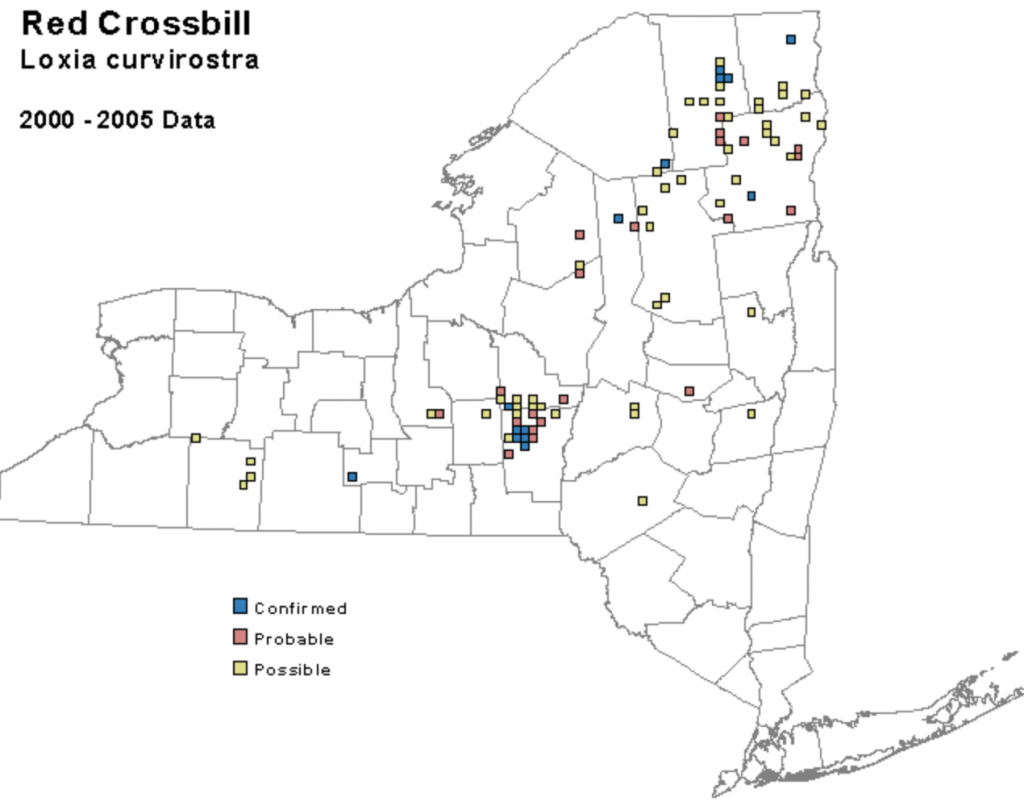

Most birders experience red crossbills as either a rare wintertime treat or as a target encounter on a trip to montane and boreal forests. However, these birds aren’t restricted just to their stereotypical habitats, provided you know when and where to look.

This past early August weekend, Matt Young and I drove around Chenango County in Central New York on a quest for breeding red crossbills. It might not look like crossbill habitat to the untrained eye, as farmland and small towns break up patches of mixed coniferous and deciduous forest on the rolling hills of the Allegheny Plateau. But a history of human development has left these forests with a wide selection and density of cone-bearing trees—enough that some of these charismatic finches choose to raise broods here annually.

Any successful crossbill search requires, first and foremost, conifer trees. Crossbills’ signature crossed mandibles evolved to pry open the scales of closed conifer cones and then grab the seed inside, seeds that would be less accessible to birds without such adaptations. Obviously, these trees must also be fully stocked with cones for the birds and their offspring to eat.

When Matt and I arrived early at our first spot in Pharsalia Woods State Forest, the food appeared bountiful. Neat plantations of Norway spruces fifty feet or taller lined the road, each tree comically loaded with green and some nearly brown sausage-sized cones. We stepped out of the car to listen. Most conifers produce cones on a cycle that begins in the summer, and the birds follow them in kind, breed, and then move elsewhere once the local cones have dropped all of their seeds. Clearly, this summer marks the start of a promising cone year.

We listened as flyover goldfinches made their “potato chip” call, red-eyed and blue-headed vireos whistled their question-and-answer songs, and red squirrels began to chitter, but nothing sounded like the signature “kip kip kip” of a red crossbill. We made a few stops along the road, but spent more time chatting about politics. The forest held tastier meals than these giant spruce cones.

The classical crossbill story goes that western North America’s vast forests of only a few conifer species have caused different groups of red crossbills to specialize on different key trees. Such isn’t the story in eastern North America south of the boreal forest, however, where conifer density is lower but conifer diversity is higher. And, Matt explained, despite the impressive Norway spruce crop, these large cones take a lot of work for the birds to pry open. We’d have to think like a crossbill: smaller, softer cones are easier to open and therefore the first food choice. The birds switch over to these harder Norway spruces, plus white pines and red pines if they’re available, later in the year once they run out of soft cones.

We continued moving through the forest, stopping half-heartedly at Norway spruce stands, before pulling over in a small, wet valley. Between alder flycatcher songs, we saw some of our first white spruces, a native small-coned spruce—and each one was stocked with a cone buffet. There weren’t any birds, but it seemed like we were on the right track.

This part of central New York wouldn’t have been a place for crossbills 200 years ago. After the Revolutionary War, European settlers forced most of the Iroquois out of the area, cleared the forest, and attempted to farm the land. However, much of the thin and acidic soil wasn’t ripe for the settlers’ farming techniques and crops, and they abandoned the land to farm elsewhere. During the early 20th century, especially during the New Deal era of the 1930s, New York State acquired much of this land and reforested it with conifers, which were a quick and easy solution for growing trees in the poor soil.

We headed west through the forest, stopping and listening at the occasional white spruce stand, until we crested a hill and saw before us a sea of conifers: Native white and red spruces, eastern hemlock, and introduced Norway and blue spruces, all full of cones. We heard the birds before we stopped the car, and across the road, a male and a female red crossbill were making their signature flight call. Red crossbills are broken into different groups based on the quality of their call, and even at a distance, Matt could tell that the birds were the Type 1 – Appalachian red crossbill, the expected crossbill type during the summertime in this region.

As we walked over to the spruce stand, a man came out of his house to greet us. An extremely astute birder, he couldn’t believe his eyes when he first saw the crossbills land in front of his house earlier this year to eat the roadside grit that aids in seed digestion. He reported that at least a dozen birds, both male and female, had been there every day in the week before we came.

Ultimately, Matt and I saw at least seven birds in this spot—four birds we could identify as Type 1 based on their kip-kip call, and three silent flyovers. The vocal birds each came as a male-female pair, and in one case, a perched on a telephone wire where the male sang to his partner. Though we couldn’t confirm that the birds were breeding, we exchanged contact information with the homeowner who said he’d monitor the birds for signs of nesting behavior or juveniles. You can see our eBird checklist with photos and a recording of the birds here.

While red crossbills move erratically, finding them doesn’t have to be a total mystery. If you learn about your local conifers and state forests, you, too, might be able to start thinking like a crossbill—and you might uncover crossbills in surprising places.

If you’re interested in keeping up with updates from the Finch Research Network, please consider subscribing to our email list here: https://finchnetwork.org/subscribe

FiRN is a nonprofit, and has been granted 501c3 status. FiRN is committed to researching and protecting these birds and other threatened finch species like the Evening Grosbeak and Rosy-finches, and if you have been enjoying all the blogs and identifying of Red Crossbill call types, redpoll subspecies and green morph Pine Siskins FiRN has helped with, please think about supporting our efforts and making a small donation at the donate link below. We plan to support student research projects and more.

Wildside Nature Tours and The Finchmasters – Finch Research Network (FiRN) are very excited to team up for our first partnership tour focusing on finch species of the Pacific Northwest! We’re really stoked about this. Its going to fun to be working with Alex Lamoreaux and Wildside Nature Tours. Let us know if you’re interested or have any questions. Read below for trip details.