Fall 2020 Irruption in Review: The Three Usual Suspects Have a Big Year

by Joe Gyekis

In the east, Purple Finches, Pine Siskins, and Red-breasted Nuthatches are the feeder birds that have the most frequent and large-scale irruptions. These birds breed in the northern conifer forests and seem happy to brave the cold as long as there is enough food to keep them warm through the long winter nights. However, when natural food supplies are slim across large regions of the north, greater than usual numbers of birds depart, sometimes spreading all the way into the southeastern US. The distance the birds travel probably depends on the conditions they encounter–if they arrive in an area with abundant food, they are more likely to stay, but if food supplies are poor again, why stick around?

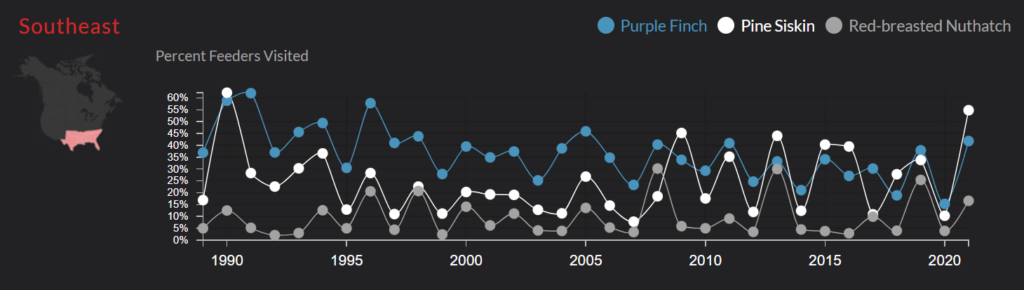

Although the three species’ irruptions are not perfectly synchronized, the data from Project FeederWatch in the southeastern US show that the three species tend to follow similar patterns of arrival to the south (Figure 1).

For each of the three species, let’s review some eBird data and migration counts from eastern sites posting to Trektellen to illustrate the timing and extent of the irruption.

Purple Finch

Some Purple Finches migrate in the east every fall, but the numbers in fall 2020 were high. As seen on the last figure, the percentage of feeders in the south that had Purple Finches by early 2021 was about tied for the highest in about 10 years. At Cape May Bird Observatory’s fall passerine migration count at Higbee Beach, there was a fabulous fall total.

To put it in perspective, 436 were counted in the whole fall season of 2016, none were counted in fall of 2017, 3196 were counted in fall of 2018, 0 were counted in 2019, and in fall 2020, 3682 were counted. Up north at Tadoussac Bird Observatory along the shores of the mouth of the St. Lawrence River (Kaniatarowanenneh is an older name), the counts had already peaked by late August, but the biggest flight day in Cape May was Oct 26th, when 577 were counted at Higbee.

There are some beautiful maps of the range of the Purple Finch on the eBird website (https://ebird.org/science/status-and-trends/purfin), including abundance animations that show–averaged across many years–the typical timing and extent of Purple Finch migrations. However, for the purposes of this blog, I created a much more simplified map that only shows the areas where Purple Finches were more abundant (redder) or less abundant (bluer) during the fall 2020 to spring 2021 abundance cycle (Figure 2).

The major take home messages of the analysis are that in September birders across the northeast found Purple Finches far more often compared to the prior year, and by October and November that spread into the south, settling in for the winter with high abundance down south while southern Canada experienced fewer than usual Purple Finches. Suddenly in April that southern abundance evaporated and by May the abundance in Canada was back up, pretty close to normal levels throughout the whole range. The irruption was over.

Pine Siskin

There are some special patterns in the Pine Siskin irruptions. They’re famous for having some irruptions moving north-south while other irruptions move east-west. The greater continent-wide complexity of the Pine Siskin story can be seen in Figure 3, which maps interannual change in eBird reporting for Pine Siskins using the same methods as described above.

In late summer, Pine Siskins were already being found by birders in the west at higher rates than normal, then suddenly in October the whole country was reporting Pine Siskins at higher rates than normal, mostly staying that way throughout the winter except for eastern Canada which had fairly low numbers compared to the prior year in winter and spring.

At the migration spots at Tadoussac and Cape May mentioned above, the pattern was pretty similar to Purple Finch, with the main difference being that the high counts at Cape May were far higher. On the biggest day at Higbee, Oct 25th, more than 11 thousand Pine Siskins were counted! Fall 2020 Cape May totals added up to over 40 thousand, but in 2018 the whole season total was only about 1 thousand.

One mystery of the Pine Siskins is how few were seen in the spring return flight compared to the fall irruption. Although there were some good counts, such as the 162 reported at Derby Hill Hawk Watch on May 3, it wasn’t quite as dramatic as the many thousand+ count days from the fall. One theory was that many of the birds flexed their migratory muscles even more strongly on the return flight, flying high and far to return to the breeding grounds. Some were detected calling in nocturnal migration in spring, in addition to the fall nocturnal flight call detections described in a prior FiRN blog post. It would be interesting if future research could test the hypothesis that irruptive finches move faster in spring migration than fall.

Red-breasted Nuthatch

While not finches, Red-breasted Nuthatches nest in many of the same forests and depend on many of the same food sources as the two finches mentioned above, and thus irrupt with some similar patterns. Like Purple Finches and Pine Siskins, their fall 2020 boom was already underway in late summer, the irruption expanded into the southern regions in September and October, lasted into the winter, and faded away in the spring. While Purple Finches didn’t irrupt much in the west, Red-breasted Nuthatch showed a lot of year-to-year change in abundance in the west, with some complex patterns of difference from region to region, somewhat like Pine Siskin in that respect.

Back east, the top count at Tadoussac was modest, 32 birds on September 29th, but it would be interesting to know if big flights might have taken place in early August or July before the fall count began. At Cape May, the season total was 2866 birds, higher than the last irruption year, 2018, when 1656 were counted. The 2020 peak count day there was October 3rd (about 3 weeks earlier than the other species), when 434 were counted. At least two were found on Bermuda in the fall, showing the power of these short winged little birds to cross vast expanses of open water. One was also found in Tamaulipas, Mexico, far south of their typical irruption range.

For birders, it’s a joy to see these fun winter visitors. For birds, it’s a tough journey, filled with Merlins grabbing birdie snacks at migrant traps and far more glass windows and salmonella infected feeding stations than they would likely find in the boreal forests. However, although getting through an irruption was surely not easy, it’s a fantastic life history strategy. Thanks to the available habitat to the south, these birds can maintain far higher population levels than they would if they, like the rodents of the boreal forest, had to make do with the very minimal food supplies in the north woods during the low mast production years. I like to think of it as teamwork between the northern forests and the southern forests to support the populations of these delightful species.

References

Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology. Project Feederwatch. https://feederwatch.org/explore/trend-graphs/ Accessed October 2021.

Sullivan, B.L., C.L. Wood, M.J. Iliff, R.E. Bonney, D. Fink, and S. Kelling. 2009. eBird: a citizen-based bird observation network in the biological sciences. Biological Conservation 142: 2282-2292.

Troost, G. Trektellen. https://www.trektellen.org/ Accessed October 2021. Data contributed by Cape May Bird Observatory and Tadoussac Bird Observatory.

If you’re interested in keeping up with updates from the Finch Research Network, please consider subscribing to our email list here: https://finchnetwork.org/subscribe

FiRN is a nonprofit, and has been granted 501c3 status. FiRN is committed to researching and protecting these birds and other threatened finch species like the Evening Grosbeak and Rosy-finches, and if you have been enjoying all the blogs and identifying of Red Crossbill call types, redpoll subspecies and green morph Pine Siskins FiRN has helped with, please think about supporting our efforts and making a small donation at the donate link below. We plan to support student research projects and more.

https://finchnetwork.org/donate

Wildside Nature Tours and The Finchmasters – Finch Research Network (FiRN) are very excited to team up for our first partnership tour focusing on finch species of the Pacific Northwest! We’re really stoked about this. Its going to fun to be working with Alex Lamoreaux and Wildside Nature Tours. Let us know if you’re interested or have any questions. Read below for trip details.

https://finchnetwork.org/wildside-nature-tours-and-the-finchmasters-finch-research-network-firn